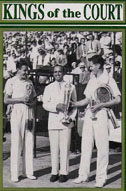

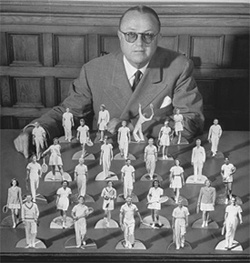

Perry T. Jones:

Dictator, Sadist, Genius

Ed Atkinson

Could it be that one man, and one man alone, could thoroughly and completely dominate and control an international sport for nearly four decades? The answer is yes. The sport is tennis. The man was Perry T. Jones.

In his youth, Jones was an avid and respectable tennis player. However, his devotion to the game evolved into a burning obsession to achieve complete control of the sport. A formidable and unlikely goal, but one he succeeded in reaching.

Jones believed that by developing a stable of great male and female players over whom he had complete control, he could hold every tournament in the world hostage by threatening not to send his players to any tournament that displeased him in any way. He thought of the players as pawns, which they were exactly in his hands

He chose an ideal location for the birth of his plan: The Los Angeles Tennis Club, which as Tom LeCompte's beautiful articles demonstrate, became the mecca for the greatest players in the game. (Click Here for Part 1. Click Here for Part 2.)

Indoor courts were extremely rare anywhere in the country. In Southern California, tennis could be b played 12 months a year. His players would have as much as 5 months more to practice compared to their rivals in the East and Midwest.

Leasing an office in the Los Angeles Tennis Club, Jones formed the Southern California Tennis Association. It became the most powerful and most feared entity in tennis.

Jones populated the Board of Directors of the new association with some of the most prominent men in the Los Angeles business community and the motion picture industry.

He embarked on a very energetic fund raising campaign, an enterprise at which he proved to be a master.

Amassing the Pawns

Jones then turned to amassing his stable. Studying junior results throughout the state, he targeted players and contacted their parents. He told them if they brought their children to his club he would provide free lessons and competition. If they were promising he would see that they obtained free rackets and the Association would pay all expenses for travel to tournaments nationwide.

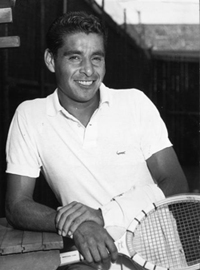

The assembly line of champions was born. Among the legendary names: Bobby Riggs, Jack Kramer, Donald Budge, Bob Falkenburg, Budge Patty, Gene Mako, Herb Flam, Ted Schroeder, Stan Smith, Dennis Ralston, even Pancho Gonzales, after he served a suspension from tournaments at Jones hands. (More on that below.)

It was true of the women as well: Pauline Betts, Louise Brough, Maureen Connolly, Gussie Moran, Billie Jean King, Darlene Hard, Sally Moore and so on ad infinitum.

If you got to the singles final of the Southern California junior championship, or if you won the doubles you got the red carpet from Jones. Once you were out of the juniors he would send you to play throughout the country and the world, and you would fly first class.

In those days players agreed to a certain amount of cash to appear in the top tournaments. It was illegal and under the table.

All the players eagerly awaited Monday, typically the tournament's first day to pick up their envelopes. All the players that is except those from Southern California.

Perry Jones conducted all negotiations for illegal appearance money for his players. The money was then forwarded directly to him. No player knew what Jones had negotiated - only that they received the amount Jones felt they deserved, an amount directly tied to staying in his good favor.

Life on the Red Carpet

I was lucky enough myself to qualify for the Jones red carpet, and so as a 19 year old I traveled on the circuit loaded with stars. I was an unranked rookie but coming from Southern California, I was treated like a champion.

Before leaving to play, Jones would give me my plane tickets, some travelers checks, and say, "Now remember Eddie, write to me once a week, and if anyone is mean to you, let me know immediately."

Upon arrival I would be picked up by tournament volunteers and watch former Wimbledon champions try to hail cabs. I received my payments from Jones like clockwork.

Then in my second year on the men's circuit, suddenly one week there was no payment. Letting a few days pass, I telephoned Jones to ask why. "Eddie," he said, "it seems you have decided to pay your expenses by playing poker and you don't need the association's money."

Yes, I and many other players had a running poker game from tournament to tournament. But how could Jones have learned of that? He had eyes and ears everywhere. I promised I would quit poker and told him I needed the money.

By the time I was swept into his system, Jones already had an enormous number of champions under similar control. This was so intimidating to tournament committees, that he actually dictated the seedings at the major events worldwide.

Once when I was in his office the phone range and Jones told the caller "for the very last time," that a certain seeding order should be changed. When he hung up he said to me, "Those people at Wimbledon think they know how to run a tournament."

Seven Wimbledon Champions

How deep was the talent at the Los Angeles Tennis Club? 8 male members decided to put $50 each in a pool and play a round robin, winner take all. The players asked the club pro, George Toley, who went on to become a legendary college coach at USC, to set it up. When he met the players in the locker room to announce the pairings he said:

"You know it's kind of amazing, seven of you guys have won the Wimbledon singles." The eighth player was Pancho Gonzales.

After winning the Wimbledon singles, the doubles, and the mixed on his first appearance Bobby Riggs told the British press. "Now I've got to do something really tough. Win the Los Angeles Tennis Club singles championship." He never did.

Despite his genius, Jones has a dark side, which was petty, sadistic, and worse, racially bigoted.

To give one example, during junior tournaments he would tour the courts and, in the middle of matches, summon a player to inform him he had been defaulted for dirty shoes, or an untucked shirt.

I can personally attest to how much he enjoyed these psychological power plays. In 1956, I had won the Southern California junior doubles title for the second year in a row, and had locked up the spot to travel all expenses paid to the Midwestern tournaments. My bags were packed but the day before leaving I was summoned to the office by Jones.

"Eddie," he said, "I am not sending you this year." Never mind that my partner and I would undoubtedly be the first seed at Kalamazoo.

Barely keeping my composure I replied, "Do you mind if I ask why?"

"Your hair is too long," he replied.

"Can I do something about that?" I asked. "Maybe," Jones said.

I literally ran from his office and raced to the barber shop, taking a short cut by climbing over the back fence at the club. I told the barber to cut until he saw bone.

I sprinted back to Jones' office. "Why Eddie," he said, you look wonderful." He then sent me to his secretary to receive my tickets and cash.

In retrospect, a funny story, though terrifying to me at the time. But what was not funny in the slightest was his bigoted treatment of minority players.

When Pancho Gonzales was creating a reputation in his teens in South Central LA, Jones banned him for one year. Jones claimed the reason was Pancho had quit school, but everyone knew the real reasons were first that he was Mexican, and second, he had defied Jones.

Another outrageous display of unfairness involved two promising young Afro-American players. When they entered the qualifying at the Pacific Southwest championships, they played each other in the first round. The winner faced the first seed. This happened two years in a row.

With the advent of open tennis, Jones' empire vanished overnight. Now the tournaments, not Jones, supplied the players their money - and far, far more money than any of them had ever received in an envelope from the dictator.

Perhaps it's not a coincidence that he died 2 years later. But what a run. the man was was a developer of champions, the most powerful man in tennis, and a deeply flawed human being. A man whose like we are highly unlikely to ever see again.