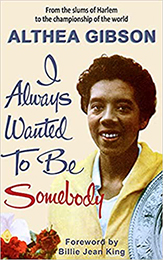

I Always Wanted To Be Somebody

Althea Gibson

I always wanted to be somebody. I guess that's why I kept running away from home when I was a kid even though I took some terrible whippings for it.

It's why I took to tennis right away and kept working at it, even though I was the wildest tomboy you ever saw and my strong likings were a mile away from what the tennis people wanted me to do.

It's why I've been willing to live like a gypsy all these years, always being a guest in other people's houses and doing things the way they said, even though what I've always craved is to live the way I want to in a place of my own with nobody to answer to but myself.

It's why, ever since I was a wild, arrogant girl in my teens, playing stickball and basketball and baseball and paddle tennis and even football in the streets in the daytime and hanging around bowling alleys half the night, I've worshiped Sugar Ray Robinson.

It wasn't just because he was a wonderful fellow, and good to me when there was no special reason for him to be; it was because he was somebody, and I was determined that I was going to be somebody, too--if it killed me.

If I've made it, it's half because I was game to take a wicked amount of punishment along the way and half because there were an awful lot of people who cared, enough to help me. It has been a bewildering, challenging, exhausting experience, often more painful than pleasurable, more sad than happy. But I wouldn't have missed it for the world.

Not many people know the real story of my life before I got into the newspapers. I'm going to try to put it all down here, just the way I lived it and just the way I remember it. If you get to thinking it isn't all pretty, remember, I never said it was.

They tell me I was born on August 25, 1927, in a small town in South Carolina called Silver. I don't remember anything about Carolina. All I remember is New York.

But my daddy talks about it a lot. He describes it as a three-store town, meaning that it wasn't as small as towns that only have one store for all the people. But it wasn't very big, either.

My father, Daniel, and my mother, Annie, both lived in Silver. "I used to walk a mile over the bridge to see her once a week," he tells everybody. "Every Sunday night I went."

And if you ask him how come he went to see Morn only once a week, he laughs and says, "Very simple. Cause that's all her people would allow it, that's why."

After they got married, my mother and father lived in a little cabin on a cotton farm. Daddy was helping one of my uncles sharecrop cotton and com, and there was plenty of hard work to go around.

Daddy is a powerfully built man-he looks a lot like Roy Campanella, the famous Dodger catcher-and Mom is a strong woman; they had no trouble meeting the requirements. Mom is the first one to say that she was no delicate flower in those days. She used to love to ride, and because there wasn't much chance of her going to a riding stable, she used to ride not only horses but cows, hogs and everything. "Sure," she told me once, "I'd jump on that cow or that hog just like it was a horse. I believe I really could do some of that right now."

I believe she could, too. She looks ten years younger than she is, and she's in shape. I was no weakling myself when I was born. I was the first child in the family, and I weighed a solid eight pounds. "You were what you call a big fat one," Mom says.

It's too bad I wasn't big enough to be of some help on the farm. They could have used me. Daddy and my uncle only had five acres of land and they never had a chance of making out. Even if things had gone well, they couldn't have put anything by.

But when bad weather ruined the crops three years in a row, they were in bad shape. "I worked three years for nothing,'" Daddy says. "That third year, all I got out of it was a bale and a half of cotton. Cotton was sellin' for fifty dollars a bale then, so I made seventy-five dollars for the year's work.

I had to get out of there, and when Mom's sister, Sally Washington, came down from New York for their sister Blanche's funeral, I made up my mind it was time." What Daddy did was agree to let Aunt Sally take me back to New York with her on the understanding that he would come up a couple of months later and get a job, and then, as soon as he could, send for Mom.

He came as soon as he got the cash for his bale and a half of cotton. "I bought me a cheap blue suit for seven dollars and fifty cents," he says, "I paid twenty-five dollars for the fare, I left some money with the wife, and I took off for New York City." I never get tired of hearing Daddy tell about what happened to him when he got off the train in New York. He had been talking to this porter on the train, telling him how bad things had been in South Carolina, and when the train pulled into Pennsylvania Station he asked the porter how to get to Harlem.

The porter said it was pretty hard even for somebody who knew his way around the city, but that he could spare an hour to guide him if Daddy wanted to pay him five dollars for his time and trouble. Daddy agreed, and the porter took him over to the subway and got on with him.

After about twenty minutes, he led him out on the sidewalk at 125th Street and said, "Here you are, Mr. Gibson. This is Harlem." And so Daddy started his life in the big city by paying five do1lars for a nickel ride on the subway.

"But that was all right," I remember Daddy saying at a party once. "It didn't make no difference. I got me a job right away, handyman in a garage, for big money. Ten dollars a week. I didn't have nothin' to worry about no more. I sent for my wife and we were in business."

We all lived together in Aunt Sally's apartment for quite a while before Daddy and Mom got an apartment of their own. I was only three years old when Aunt Sally first brought me up with her, and I don't remember very much about what it was like at her place.

I do know she made good money selling bootleg whisky. I don't think she actually made the stuff, I think she just sold it. Whether or not she had any other source of income, I don't know, but if she did, it was closely mixed up with selling the whisky to the men who were always coming to the house.

I know one thing. There was always lots of food to eat in her house, the rent was always paid on time, and Aunt Sally wore nice clothes every day in the week. She did all right for herself. There was one time when her business was bad for me.

I was in my bedroom, sleeping, and Aunt Sally was in the parlor with her company. I woke up feeling awful thirsty and I got up to get a glass of water in the kitchen. I noticed a big jug on the kitchen table, and it looked good, so without even thinking twice, I grabbed it and turned it up.

The next thing I can remember is Aunt Sally holding me down in the bed while the doctor pumped my stomach out. According to Daddy, that was far from the last time in my kid days that I put away a lot of whisky.

Some of my uncles, and some of the other men who came to see Aunt Sally, used to take me out with them for the afternoon, and naturally they would always end up drinking whisky. So would I.

They gave it to me in a water glass, and without any water in it, either. Daddy claims that I never used to get drunk but that when I got home he had to get all the whisky out of me. I don't ask him anymore how he managed to do it but I have a better than vague recollection that it had something to do with sticking two of his fingers down my throat.

I don't recommend this kind of childhood training, but I will say one thing for it--I don't think I'll ever disgrace myself by getting drunk in public. I've built up a sort of immunity. When I was about seven or eight, I went to Philadelphia to live for a while with my aunt Daisy Kelly, who lives in the Bronx now, in New York City.

I stayed with Aunt Daisy off and on for a couple of years, and I must have given her plenty of trouble, although now she just makes it all sound kind of comical. I've heard her tell one story a hundred times, and no matter how funny it sounds now, it must have been a sore trial at the time.

Aunt Daisy had this friend who owned a secondhand automobile, and I admired the car and him very much. I used to follow him around everywhere. "This particular morning," Aunt Daisy says, "it was Sunday, and I'd got you all dressed up in a beautiful white dress, with white stockings and even a white silk bow in your hair. Then I let you go out.

You were gone a long time, and after a while I began to get worried, so I started looking out the window for you.

"And there that man was working on his car, and he had an open bucket of grease standing on the sidewalk next to it, and you were jumping across the bucket, first from one side and then from the other. And sure enough, just when I was sucking in air to scream at you, you slipped and fell right in the damn bucket. You looked like Amos and Andy. I couldn't get the last of that grease off you for days, and the dress—I just had to throw the dress away."

Another day, Aunt Daisy says, when I was gone long, I finally came around the corner with a great big branch of a tree in my hand, and two boys running after me as hard as they could run. According to Aunt Daisy, just when it looked like they were going to catch up to me and really give it to me, I turned around and started swinging that branch on them. "You just railed them and railed them," she says. "I started out being scared that you were going to get hurt, and I wound up being scared that you would hurt them bad."

I could always take care of myself pretty well, that's a fact. I think the worst fright I ever gave Aunt Daisy was once when she and my cousin Pearl were going somewhere in a friend's car, and I wasn't supposed to go. I kicked up a storm and then quietly made up my mind what I was going to do.

When the car pulled up at the house they were going to, and Aunt Daisy and Pearl got out, I was standing on the sidewalk. I had made the whole trip standing on the running board and holding on to the door handle, with my head scrooched down underneath the window so nobody could see me.

But I didn't start getting into real trouble until the Gibson family settled into a place of its own, the apartment on West 143rd Street in which my mother and father, my sisters, Millie and Annie and Lillian, and my brother Daniel, still live. I was a traveling girl, and I hated to go to school.

What's more, I didn't like people telling me what to do. Take it from me, you can get in a lot of hot water thinking like that. I played hooky from school all the time. It was a habit I never lost. Later on, when I got bigger, my friends and I used to regard school as just a good place to meet and make our plans for what we would do all day.

When I was littler, the teachers used to try to change me; sometimes they would even spank me right in the classroom. But it didn't make any difference, I'd play hooky again the next day.

Daddy would whip me, too, and I'm not talking about spankings. He would whip me good, with a strap on my bare skin, and there was nothing funny about it. Sometimes I would be scared to go home and I would go to the police station on 135th Street and tell them that I was afraid to go home because my father was going to beat me up.

The first time I did it, the cops let me stay there for about an hour and then they called Mom and told her to come and get me. But she was afraid to go. She didn't want any part of police stations. So, finally, the desk sergeant sent a young cop over to the house to ask her, "Don't you want your daughter?" I got it good that night.

The only thing I really liked to do was play ball. Basketball was my favorite, but any kind of ball would do. I guess the main reason why I hated to go to school was because I couldn't see any point in wasting all that time that I could be spending shooting baskets in the playground.

"She was always the outdoor type," Daddy told a reporter once. "That's why she can beat that tennis ball like nobody's business." If I had gone to school once in a while like I was supposed to, Daddy wouldn't have minded my being a tomboy at all. In fact, I'm convinced that he was disappointed when I was born that I wasn't a boy.

He wanted a son. So he always treated me like one, right from when I was a little tot in Carolina and we used to shoot marbles in the dirt road with acorns for marbles. He claims I used to beat him all the time but seeing that I was only three years old then, I think he's exaggerating a little bit.

One thing he isn't exaggerating about, though, is when he says he wanted me to be a prize fighter. He really did. It was when I was in junior high school, like maybe twelve or thirteen years old, and he'd been reading a lot about professional bouts between women boxers, sort of like the women's wrestling they have in some parts of the country today.

Women's boxing is illegal now but in those days it used to draw some pretty good small-club gates. Daddy wanted to put me in for it. "It would have been big," he says. "You would have been the champion of the world. You were big and strong, and you could hit." I know it sounds indelicate, corning from a girl, but I could fight, too.

Daddy taught me the moves, and I had the right temperament for it. I was tough, I wasn't afraid of anybody, not even him. He says himself that when he would whip me, I would never cry, not if it killed me. I would just sit there and look at him. I wouldn't sass him back or anything, but neither would I give him the satisfaction of crying.

He would be doing all the hitting and all the talking, and I guess after a while it must have seemed like a terrible waste of time. He liked our boxing lessons better.