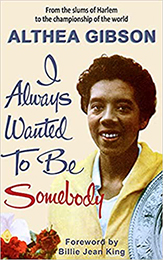

I Always Wanted To Be Somebody

Part 2

Althea Gibson

Once he got the idea of me boxing professionally out of his head, all Daddy was trying to do, aside from teach me right from wrong, was to make sure I would be able to protect myself. Harlem is a mean place to grow up in; there's always somebody to gall you no matter how much you want to mind your own business.

If Daddy hadn't shown me how to look out for myself, I would have got into a lot of fights that I would have lost, and I would have been pretty badly beaten up a lot of times.

I remember once I was walking down the street with a bunch of pebbles in my hand, throwing them at targets like street signs and mailboxes and garbage cans, and this big girl came up to me and said, "What, are you supposed to be tough or something? You're supposed to be bad?" I tried to pay no mind to her. I wanted to avoid her. But she wouldn't let me. She hauled off and hit me right in the breadbasket and I went down to my knees, in agony. I prayed that she wouldn't hit me again while I was trying to get my breath back. But she didn't; she just walked away, and I ran home crying. Daddy didn't give me any sympathy at all. When I told him what had happened, he said, "If you don't go back out there and find her and whip her, I'll whip the behind off you when you come home."

So I went back and I found her and I beat the hell out of her. I really tore into her. I kept hitting and hitting, and I wasn't hitting like a girl, either, I was punching.

Every time I hit her in the belly and she doubled up with the pain, I straightened her up again with a punch in the face. I didn't show her any mercy, but I guarantee you one thing, she never bothered me again.

Sometimes, in a tough neighborhood, where there is no way for a kid to prove himself except by playing games and fighting, you've got to establish a record for being able to look out for yourself before they will leave you alone. If they think you're an easy mark, they will all look to build up their own reputations by beating up on you.

The First Punch

I learned always to get in the first punch. There was one fight I had with a big girl who sat in back of me in school. Maybe because I wasn't there very often, she made life miserable for me when I did show up.

I used to wear my hair long, in pigtails, then, and she would yank on those pigtails until I thought she was going to tear my hair out by the roots. If I turned around and asked her to leave me alone, she would just pull harder the next time.

So one day I told her I'd had all of that stuff I was going to take, and I'd meet her outside after school and we would see just how bad she was. The word that there was going to be a fight spread all around the school, and by the time I walked outside that afternoon, she was standing in the playground waiting for me, and half the school was standing behind her ready to see the fun.

I was scared. I wished I hadn't started the whole thing. She was a lot bigger than me, and she had the reputation of being a tough fighter. But I didn't have any choice. I had to save my face the best way I could. Anyway, my whole gang was behind me, pushing me right up to her. We stood there for a minute or so, our faces shoved up against each other, the way kids will do, and we cursed each other and said what we were going to do to each other.

Meanwhile I tried to get myself into position, so I'd have enough leverage to get off a good punch. She had just got through calling me a pig-tailed bitch when I let her have it. I brought my right hand all the way up from the floor and smashed her right in the face with all my might.

I hit her so hard she just fell like a lump. Honest to God, she was out cold. Everybody backed away from me and just stared at me, and I turned around like I was Joe Louis and walked on home. It wasn't only girls that I fought, either.

I had one terrible fight with a boy, on account of my Uncle Junie, who was Aunt Sally Washington's brother, Charlie. They were living on 144th Street, just off Edgecombe, and there was a tough gang on the block called the Sabres.

The leader of the gang and I used to pal around together a lot; we played stickball and basketball and everything. No loving up, though. I wasn't his girl. We were what we called boon-coons, which in Harlem means block buddies, good friends.

Well, this one day I'd been up visiting Aunt Sally, and on my way out, just as I turned around the last landing, I saw Uncle Junie lolling on the stairs, slightly intoxicated, and this Sabre leader was standing over him going through his pockets.

What you doin'?" I hollered down at him. "That's my uncle! Go bother somebody else if you got to steal, but don't bother him!" I ran down and-lifted Uncle Junie up, got him turned around, and started to help him up the stairs. Then I looked back over my shoulder to see if the kid was leaving, and I was just in time to see him take a sharpened screwdriver out of his pocket and throw it at me.

I stuck my hand out to protect myself and got a gash just above my thumb that still shows a scar as plain as day. Well, I got Uncle Junie upstairs as quick as I could and went back down after that boy and we had a fight that they still talk about on 144th Street. We fought all over the block, and first he was down and then I was down, but neither of us would stay down if we died for it.

He didn't even think of me as a girl, I can assure you. He fought me with his fists and his elbows and his knees and even his teeth. We were both pretty bloody and bruised when some big people finally stopped it, and I guess you would have to say it was a draw.

But at least those Sabres respected me from then on. None of them ever tried to use me for a dartboard again. Once I took a punch at Uncle Junie himself. I walked into his apartment one night when he was having a big fight with his wife, Mabel. Just as I came in, Uncle Junie hauled off and slapped Mabel as hard as he could, right across her face. Well, that was all I had to see.

I was little lady Robin Hood in the flesh. I sashayed right up to him and punched him in the jaw as hard as I could and knocked him down on his back. "What the hell are you hittin' Mabel like that for?" I hollered at him. I was lucky he didn't get up and knock all my teeth out.

Snitching

Except for the fights I got into, and playing hooky all the time, I didn't get into much serious trouble when I was a kid or do anything very bad. I guess about the worst thing we did was snitch little packages of ice cream while we were walking through the big stores like the five-and-ten, or pieces of fruit while we were walking past a stand on the street.

I remember once a gang of us decided we would snitch some yams for roasting, and I strolled nonchalantly past the stand and casually lifted one. Once I had it, though, I couldn't resist the impulse to run, and a cop who was standing on the comer got curious and grabbed me for good luck.

He had me cold; I had that damn yam right in my hand. I'd have run if I could, but he had a death grip on my arm and he dragged me over to the police call box and made like he was going to call up for the wagon to come and get me. I was scared.

I begged him to let me go. I swore I'd be a good girl for the whole rest of my life. Finally, he said he would give me a break, and he took me over to the stand and made me put back the yam, and then he let me go.

But when I walked around the comer and found the rest of the girls I'd been with, they dared me to go back and get it again, and I was just bold enough to take the dare. I got it, too, and got away clean, and we went and built a fire on an empty lot in the next block and roasted it.

Sometimes we used to go across the 145th Street Bridge to the Bronx Terminal Market, where all the freight cars full of fruits and vegetables are broken down for the wholesalers. That was a snitcher's heaven.

They used to stack rejects off to one side, stuff that the wholesalers wouldn't accept, and we'd sneak in with empty baskets and try to fill them up before they spotted us and came after us. Sometimes I'd get a whole basketful of overripe bananas and peaches, wilted lettuce and soft tomatoes, and we'd really gorge ourselves on the stuff.

Once I carried a whole watermelon in my hands over that bridge. Like I said, we never got in any real trouble. We were just mischievous.

I think one good thing was that I never joined any of those so-called social clubs that they've always had in Harlem. None of my girl friends did, either. We didn't care for that stuff, all the drinking and narcotics and sex that they went in for in those clubs-and we didn't care for the stickups that they turned to sooner or later in order to get money for the things they were doing.

I didn't like to go to school but I had no interest in going to jail, either. Mostly my best girl friend, Alma Irving, and I liked to play hooky and spend the day in the movies, especially on Friday, when they had a big stage show at the Apollo Theatre on 125th Street.

Alma liked to play basketball, too, almost as much as I did. She was a good basket shooter, and we'd spend hours in the park shooting for Cokes or hot dogs. We wouldchallenge anybody, boy or girl, man or woman, to play us in what we used to call two-on-two.

We'd use just one basket and see which team could score the most baskets on the other. We played hard, and when we got finished, we'd go to a cheap restaurant and get a plate of collard greens and rice, or maybe, if we were a little flush, a hamburger steak or fried chicken and French fried potatoes.

In those days, of course, you could get a big plate of food like that for only thirty-five cents. Fish and chips were only fifteen cents, and soda was a nickel a quart if you brought your own can. You could buy big sweet potatoes--we called them mickeys--for a couple of cents apiece, and they tasted awful good roasted over an open fire made out of broken-up fruit crates that we picked up in the alleyway behind the A&P.

Now I realize how poor we were in those days, and how little we had. But it didn't seem so bad then. How could you feel sorry for yourself when soda was a nickel a quart?

Adventures

We had some great adventures. I had a friend, Charles, who was twelve years old and, like me, was always ready to go.

One time we made up our minds to go to the World's Fair out on Long Island. We got together some change by scrounging all the empty soda bottles we could find and turning them in at the store; we got two cents for Coke bottles and ginger ale and soda splits, and a nickel apiece for the big quart bottles.

Then we went to the bicycle store and rented a bike for the day for thirty five cents, and we rode all the way out to the World's Fair in Flushing Meadows, taking turns with one of us driving and the other one sitting on the bar. When we got there, we walked around until we spotted a place where we could sneak in, and we had a big time all afternoon and then pedaled all the way back home to Harlem.

Another time, Charles and I rented a bike up around 145th Street, rode it down to another bicycle store a couple of blocks below 125th Street, and sold it for three dollars so we could go to Coney Island. We didn't get back home until midnight, and in the meantime the man we had rented the bike from had come to the house looking for it. We'd had to give him our names and addresses when we took it out.

Looking back on it, I have no idea how we thought we were going to get away with it. I guess we had some notion that maybe the man who owned the bike wouldn't look for it for a couple of days, and in the meantime we could make a few bucks somewhere and buy it back from the man we'd sold it to.

What happened was that the next morning Daddy took me downtown and gave the man his three dollars and got the bike back. The man didn't want to let us have it at first, but when Daddy explained that we'd stolen it, he gave it up in a hurry. He didn't want to have any trouble with the police.

I had a sore bottom for a week after that little business deal, and it wasn't from riding the handlebars, either. Poor Daddy must have wished there was some way he could whip me hard enough to make me behave like the other kids in the family.

My brother Dan and my three sisters, Millie and Annie and Lillian, never got into any trouble at all. They were good in school, too. I was the only one who was always stepping out of line.

Troubles

I think my worst troubles started when I graduated from junior high school in 1941. How I ever managed to graduate, I don't know, but I guess I was there just often enough to find out a little bit about what was going on.

Either that or they simply made up their minds to pass me on to the next school and let them worry about me. It might have worked except that I didn't like the idea of going to the Yorkville Trade School, which was where I'd been transferred to.

It wasn't that I really cared which school I went to or played hooky from; it was just that a lot of my girl friends were going to one of the downtown high schools, and I wanted to stay with them. I tried to get changed over, but they wouldn't let me, and that didn't set well with me at all.

I guess I went pretty regularly for the first year, mostly because I was interested in the sewing classes. I got to be pretty good on the sewing machine. I remember once something went wrong with the machine I was using, and I volunteered to fix it, and I did. The teacher was amazed.

But after a while I got tired of the whole thing, and from then on school and I had nothing in common at all. I began to stay out for weeks at a time, and because the truant officer would come looking for me, and then Daddy would whip me, I took to staying away from home, too.

Mom says she used to walk the streets of Harlem until two or three o'clock in the morning looking for me. But she never had much chance of finding me. When I was really trying to hide out I never went near any of the playgrounds or gymnasiums or restaurants that I usually hung out at.

I sneaked around to different friends' houses in the daytime, or sat all by myself in the movies, and then, if I didn't have any place lined up to sleep, I would just ride the subway all night. I would ride from one end of the line to the other, from Van Cortlandt Park to New Lots Avenue, back and forth like a zombie. At least it was a place to sit down.

Naturally, the longer I would stay away the worse beating I would get when I finally did go home. So I would just stay away longer the next time. It got so that my mother was afraid to let me out of the house for fear I wouldn't come back.

Sooner or later, though, she would take a chance and give me fifteen or twenty cents and send me down to the store for a loaf of bread or a bottle of milk. I would go downstairs and see the boys playing stickball in the street, and that would be the last I thought of the loaf of bread or the bottle of milk.

I would play until it got dark, spend the money on something to eat, and take off on another lonesome expedition. Once a girl friend of mine whose parents had been really cruel to her, so bad that she'd had to go to the police about it, told me there was a place on Fifth Avenue at 105th Street called the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, that would take in kids who were in trouble and had no place to go.

The next time I stayed out so late that I didn't dare go home I remembered about this place and went there and asked them to take me in. "I'm scared to go home," I told the lady in charge. "My father will whip me something awful." They took me in and gave me a bed to sleep in, in a big girls' dormitory, and it was a whole lot better than riding the subway. The beds had white sheets and everything.

The trouble was, they notified my mother and father that they had me there, and Daddy came for me in the morning and took me home. I promised him I wasn't ever going to run away again, but he licked me anyway, and a week later I took off again.

I went straight to the S.P.C.C. I told them that my father had whipped me bad, after he'd promised that he wouldn't, and I even skinned off my shirt and showed them the big red welts the strap ad put on my back.

They took me in again, and this time when Daddy came after me they asked me if I wanted to go back with him. When I said no, that I was afraid to, they said I could stay if I wanted to. I wanted to, all right. As far as I was concerned, that place was a regular country club.

I had to do a little work, like making my bed and helping clean up the dormitory, and taking my turn scrubbing the toilets, but mostly it was a snap. At home I'd had to work a lot harder, the food was nowhere near as good, and somebody was always yelling at me or, worse, hitting me.

This was my idea of living. The only time it was bad was when I got into a fight with one of the other girls and they punished me by putting me down in the solitary cell, which wasn't really a cell at all but just a little room in the basement where all you had was a mattress on the bare floor and nothing very much to eat.

I behaved myself after that experience; I didn't want to go back there again. It was too nice up in the dorm. After a while, though, I got tired of the life there. I guess it was a little too restricted for me.

So I told the head lady I wanted to go back home, and she said, all right, I could, but that if I had any more trouble they would have to send me away to the girls' correction school, which is polite language for reformatory, at Hudson, in upstate New York. They sent for Daddy and released me in his custody. I was a little nervous about what he might do, but I was glad to be going home anyway.

I want to say right here that none of this is meant to say that my father was harder on me than he ought to have been. Even though when he got mad he got very mad, he was actually a patient man.

If he had whipped me every day of my life from the time I was seven years old, I would have deserved it. I gave him a whole lot of trouble. I don't hate him for anything today. In fact, I love him. I feel a lot of those whippings he gave me helped make me what I am today. Somebody had to knock a little sense into me, and it wasn't easy.

I had no intention of going back to that Yorkville Trade School, but I was too young to get my working papers, so I had to make a deal with the school people. They let me have working papers on condition that I would go to night school a certain number of hours a week. I went for a couple of weeks, but then I stopped, and nobody ever came after me.

So that was that. I was officially a working girl. I liked it, too. I felt better, working. I had the feeling of being independent, like I was somebody, making my own money and buying what I wanted to buy, paying in a little at home and doing what I wanted to do instead of being what you might call dictated to.

It was very important to me to be on my own. I must have worked at a dozen jobs in the next few years, maybe more. I was restless and I never stayed in any one place very long. If it wasn't to my liking, I quit.

I was a counter girl at the Chambers Street branch of the Chock Full O' Nuts restaurant chain. I was a messenger for a blueprinting company. I worked in a button factory and a dress factory and a department store.

I ran an elevator in the Dixie Hotel, and I even had a job cleaning chickens in a butcher shop. I used to have to take out the guts and everything, but I still like to eat chicken. Out of all of them, I only had one job that I really liked, and I lost that one for being honest.

It was at the New York School of Social Work. I was the mail clerk, and I even had a little office of my own. It was my job to sort all the mail for the whole school, break it down and deliver it to the different offices and people, and also take care of sending out the outgoing mail.

I liked the job because it was the first one I'd had that gave me some stature, that made me feel like I was somebody. I was there for six months, the longest I ever worked at any job. I lost it because one Friday some of my girl friends were taking the day off to go to the Paramount Theatre in Times Square to see Sarah Vaughan in the stage show, and I decided I would go, too.

When I went in to work on Monday morning, the lady supervisor sent for me to come into her office, and I knew right away I was in trouble. "What happened to you on Friday?" she wanted to know. I could have lied to her and told her I'd been sick, but I didn't feel like it. I told her the truth.

"All my girl friends were going to the Paramount to see the show," I told her. "Sarah Vaughan was there. I thought maybe it wouldn't be so bad if I took just one day off. I'm sorry about it. I won't do it again, I promise."

For a minute, I thought she was going to let me off. "I must say I admire your honesty," she said. "I would much rather you told me the truth than have you lie to me. But that doesn't change the fact that your job here is particularly important to the whole organization. We've got have an especially trustworthy person in it. I had to do all the mail by myself on Friday, and it was late getting around. I simply can't have somebody in that job who would leave it untended for such a foolish reason. I'll have to let you go and get somebody else."

The kind of girl I was at the time, it wasn't easy for me to beg anybody for anything. But I really begged that lady to let me stay. "I'll never do it again," I told her, "honest I won't. I'll come to work even if I'm sick." But she wouldn't change her mind. "The only thing I can do for you," she said, "is give you a week's pay to give you a chance to find another job. But you're through here. You'll have to leave today."

It wasn't exactly the best way for me to learn that it pays to be honest, but it was a good way for me to learn that it pays to stick to your responsibilities. I sure liked that job. I hated to lose it.

For a while I didn't exactly knock myself out looking for another job. I suppose you could say I was sulking. Anyway, I just stayed away from home and bummed around the streets.

It wasn't long before a couple of women from the Welfare Department picked me up and laid down the law. If I wouldn't live home, and I wouldn't go to school, I would have to let them find me a place to stay with a good, respectable family and report to them every week so they could keep a check on me.

Either that or I would have to go away to the reformatory; one or the other. Naturally, when they put it like that, I said I would go along with what they wanted. So they got me a furnished room in a private home, and even gave me an allowance to live off while I was looking for a job.

I could hardly believe this allowance jazz. It was too good to be true. But I figured I might as well enjoy it while I could, so I forgot all about looking for a job and just spent all my time playing in the streets and the parks and going to the movies.

I went back to see my mother and father fairly often, and they made no objection to what I was doing because they figured I was in good hands with the Welfare ladies. I sure was never better. All I had to do was report in once a week and pick up my allowance. It was during this time, when I was living in a never-never land through the courtesy of the City of New York, that I was introduced to tennis. My whole life was changed, just like that, and I never even knew it was happening.