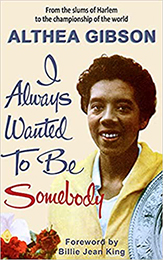

I Always Wanted To Be Somebody

Part 3

Althea Gibson

The 143rd Street block my mother and father lived on was a Police Athletic League play street, which means that the policemen put up wooden barricades at the ends of the street during the daytime and closed it to traffic so we could use it for a playground. One of the big games on the street was paddle tennis, and I was the champion of the block.

In fact, I even won some medals representing 143rd Street in competition with other Harlem play streets. I still have them, too. I guess I've kept every medal or trophy I ever won anywhere.

Paddle tennis is played on a court marked off much like a tennis court, only about half the size. You use a wooden racket instead of a gut racket, and you can play with either a sponge rubber ball or a regular tennis ball. It's a lot different from real tennis, and yet it's a lot like it, too.

There was a musician fellow, Buddy Walker, who was known as "Harlem's Society Orchestra Leader,” but who in those days didn't get much work in the summer months and filled in by working for the city as a play leader.

He was watching me play paddle tennis one day when he suddenly got the idea that I might be able to play regular tennis just as well if I got the chance. So, out of the kindness of his heart, he bought me a couple of second-hand tennis rackets for five dollars apiece and started me out hitting balls against the wall on the handball courts at Morris Park.

Buddy got very excited about how well I hit the ball, and he started telling me all about how much I would like the game and how it would be a good thing for me to become interested in it because I would meet a better class of people and have a chance to make something out of myself. He took me up to his apartment to meet his wife, Trini, and their daughter, Fern, and we all talked about it.

The next thing that happened was that Buddy took me to the Harlem River Tennis Courts at 150th Street and Seventh Avenue and had me play a couple of sets with one of his friends. He always has insisted that the way I played that day was phenomenal for a young girl with no experience, and I remember that a lot of the other players on the courts stopped their games to watch me.

It was very exciting; it was a competitive sport and I am a competitive sort of person. When one of the men who saw me play that first time, a black schoolteacher, Juan Serrell, suggested to Buddy that he would like to try to work out some way for me to play at the Cosmopolitan Tennis Club, which he belonged to, I was more than willing. The Cosmopolitan is gone now, but in those days, it was the ritzy tennis club in Harlem. All the Sugar Hill society people belonged to it.

Mr. Serrell's idea was to introduce me to the members of the Cosmopolitan and have me play a few sets with the club's one-armed professional, Fred Johnson, so that everybody could see what I could do. If I looked good enough, maybe some of them would be willing to chip in to pay for a junior membership for me and to underwrite the cost of my taking lessons from Mr. Johnson.

Lucky for me, that's the way it worked out. Everybody thought I looked like a, real good prospect, and they took up a collection and I bought me a membership. I got a regular schedule of lessons from Mr. Johnson, and I began to learn something about the game of tennis.

I already knew how to hit the ball but I didn't know why. He taught me some footwork and some court strategy, and along with that he also tried to help me improve my personal ways. He didn't like my arrogant attitude and he tried to show me why I should change.

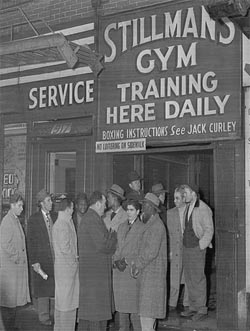

I don't think he got too far in that department; my mind was set pretty strong. I was willing to do what he said about tennis, but I figured what I did away from the courts was none of his business. I wasn't exactly ready to start studying how to be a fine lady. Those days, I probably would have been more at home training in Stillman's Gym than at the Cosmopolitan Club. I really wasn't the tennis type.

But the polite manners of the game, that seemed so silly to me at first, gradually began to appeal to me. So did the pretty white clothes.

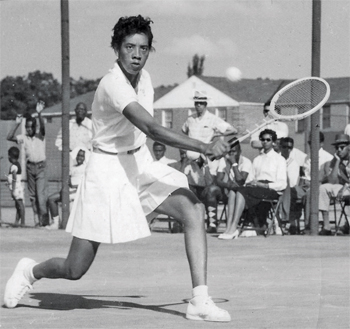

I had trouble as a competitor because I kept wanting to fight the other player every time, I started to lose a match. But I could see that certain things were expected, in fact required, in the way of behavior on a tennis court, and I made up my mind that I would go along with the program.

After a while I began to understand that you could walk out on the court like a lady, all dressed up in immaculate white, be polite to everybody, and still play like a tiger and beat the liver and lights out of the ball. I remember thinking to myself that it was kind of like a matador going into the bull ring, beautifully dressed, bowing in all directions, following the fancy rules to the letter, and all the time having nothing in mind except sticking that sword into the bull's guts and killing him as dead as hell.

I probably picked up that notion from some movie I saw. I suppose if Fred Johnson or the club members who were paying for my tennis had known the whole truth about the way I was living I wouldn't have lasted long. The Cosmopolitan members were the highest class of Harlem people and they had rigid ideas about what was socially acceptable behavior.

They were undoubtedly more strict than white people of similar position, for the obvious reason that they felt they had to be doubly careful in order to overcome the prejudiced attitude that all black people lived eight to a room in dirty houses and drank gin all day and settled all their arguments with knives. I'm ashamed to say I was still living pretty wild.

I was supposed to be looking for a job, but I didn't look very hard because I was too busy playing tennis in the daytime and having fun at night. The hardest work I did, aside from practicing tennis, was to report to the Welfare ladies once a week, tell them how I was getting along, and pick up my allowance.

Then I would celebrate by spending the whole day in the movies and filling myself up with a lot of cheap food. But I guess it would have been too much to expect me to change completely right away.

Actually, I realize now that every day I played tennis I got more interested in the game. I was changing a little bit. I just wasn't aware of it. One of the people who did a lot for me in those early days at the Cosmopolitan was Mrs. Rhoda Smith. She has been important to me ever since.

Rhoda is a well-off society woman who had lost her own daughter about ten years before I met her, and she practically adopted me. She bought me my first tennis costume and did everything she could to give me a boost.

I didn't always appreciate it, either, and I guess Rhoda was well aware of it. I clipped a newspaper story a few years ago in which she told a reporter: "I was the first woman Althea ever played tennis with, and she resented it because I was always trying to improve her ways.

I kept saying, "Don't do this,' and ‘Don't do that," and sooner or later she would holler, "Mrs. Smith, you're always pickin' on me." I guess I was, too, but I had to. When a loose ball rolled onto her court, she would simply bat it out of the way in any direction at all instead of politely sending it back to the player it belonged to, as is done in tennis. But Althea had played in the street all her life and she just didn't know any better.”

One of the days I remember best at the Cosmopolitan Club was the day Alice Marble played an exhibition match there. I can still remember saying to myself, boy, would I like to be able to play tennis like that!

She was the only woman tennis player I'd ever seen that I felt exactly that way about. Until I saw her, I'd always had eyes only for the good men players. But her effectiveness of strike, and the power that she had, impressed me terrifically.

Basically, of course, it was the aggressiveness behind her game that I liked. Watching her smack that effortless serve, and then follow it into the net and put the ball away with an overhead as good as any man's, I saw possibilities in the game of tennis that I had never seen before.

It's a funny thing. I had no way of knowing then that when the time came for me to be up for an invitation to play at Forest Hills, my biggest support aside from a handful of my own people would be this same Alice Marble.

I began taking lessons from Fred Johnson in the summer of 1941, but it wasn't until a year later that he entered me in my first tournament. The American Tennis Association, which is almost all black, was putting on a New York State Open Championship at the Cosmopolitan Club, and Fred put me in the girls' singles.

It was the first tournament I had ever played in, and I won it. I was a little surprised about winning, but not much. By this time I was accustomed to winning games.

I think what mostly made me feel good was that the girl I beat in the finals, Nina Irwin, was a white girl. I can't deny that that made the victory all the sweeter to me. It proved to my own satisfaction that I was not only as good as she was, I was better.

Nina, incidentally, also took lessons from Fred Johnson, but I think he was pleased when I won. The other members had no choice; they had to like it. I won, didn't I? Actually, even though almost all the club members were black, a lot of them probably were rooting for Nina because they thought I was too cocky and they figured it would do me good to get beat.

It's always been a fault of mine that I don't let many people get close to me, and not many of those people had any way of knowing what I was really like or what made me that way. I guess they do now.

But in those days part of my defense was in being assertive and a show-off. Just the same, winning softened a lot of opinions about me. After I showed them the championship material that was in me, things changed noticeably around the club. I found that I was accepted solely on my merits, and my attitude toward people didn't seem to matter so much anymore.

Not many people, I've found out, find fault with a winner. Later in the same year-the summer of 1942--the club took up a collection to send me to the A.T.A. national girls' championship at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. That was my first national tournament, and I lost in the finals.

The girl who beat me was Nana Davis, whose name is now Nana Davis Vaughan, and I think it's interesting to read what Nana said about that match to a reporter who talked to her after I won at Wimbledon: "Althea was a very crude creature. She had the idea she was better than anybody.

I can remember her saying, "Who's this Nana Davis? Let me at her." And after I beat I her, she headed straight for the grandstand without bothering to shake hands. Some kid had been laughing at her and she was going to throw him out.

There wasn't any A.T.A. national championship tournament in 1943 because of the war and the restrictions on travel, but I won the girls' singles in both 1944 and 1945, and then, when I turned eighteen, my life began to change.

For one thing, the social workers I had been reporting to no longer had charge of me. I wasn't a minor any more. Of course, I no longer was in line for the allowance I had been getting, either, but that didn't seem so important stacked up against the fact that I was able to run my own life at last.