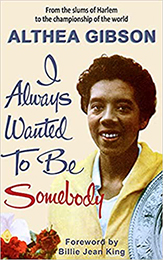

I Always Wanted To Be Somebody

Part 4

Althea Gibson

I had made friends with a girl named Gloria Nightingale, and now that I was on my own, I went to live with her in her family's apartment. I got a job as a waitress and I paid rent to Gloria's grandmother.

Gloria and I had a lot of fun together. During the winter of 1945-46, we played on the same basketball team—it was called The Mysterious Five-and we used to play as many as four or five games a week against different industrial teams. Whenever we weren't playing basketball we went bowling. Sometimes, even though it meant that we wouldn't get home until three or four in the morning, we would go bowling after we had finished a basketball game.

Gloria was like me. All she cared about was playing games and having a good time. I still consider those years the liveliest of my whole life. We were really living. No responsibilities, no worries, just balling all the time.

It was through Gloria that I met Edna Mae and Sugar Ray Robinson. Gloria had known Edna Mae for a long time, and one night when we were out bowling, we saw Ray in the place and she introduced me to him.

To show you how cocky I was, I got on him right away. "So you're Sugar Ray Robinson?" I said. "Well, I can beat you bowling right now!" I think he took a liking to me right away.

Anyway, from that night on, I used to go up to his place every chance I got. Whenever I could I would sleep there. Ray and Edna were real good friends.

I felt that they liked me, and I was crazy about them. When Ray went into the army, I stayed with Edna a lot. I was what you might call her Girl Friday. I did everything I could to make our relationship a lasting one.

When Ray was in training, I used to go and live with Edna in a place on the other side of the mountain from his camp at Greenwood Lake, New York. We used to take a long hike from our cottage to Ray's cabin-it must have been about three miles every morning, and that wonderful mountain air seemed great to a kid from 143rd Street.

Not that there was anything the matter with the air in Harlem, it was just that there were an awful lot of people using it. Both Edna and Ray were kind to me in lots of ways. They seemed to understand that I needed a whole lot of help. I used to love to be with them. They had such nice things.

Sometimes they would even let me practice driving one of their fancy cars, even though I didn't have a license. I think it gave Ray a kick to see how much fun I got out of it. Ray had a set of drums that he liked to play and I always had an inkling for music myself.

My favorite instrument was the saxophone. I just loved the sound of it. One day I asked Edna if she thought Ray would buy me one, and she said the only way to find out was to ask him.

So I did, and he told me that as long as I was really serious about it and not just fooling around, if I went to a music store or a hockshop and found one, he would pay for it. I asked a few people where I ought to go look and they said I should try down around Eighth and Ninth Streets and Third Avenue.

I went down there and saw a beautiful sax in a pawnshop window, just exactly what I wanted. The man in the store said I could have it for hundred seventy-five, and I rushed back and told Ray.

He seemed pretty skeptical. "A hundred and seventy-five dollars?" he said. "That sounds like a lot of money for a second-hand saxophone. I'll tell you what you do. You go find Buddy Walker and ask him to go down there with you. He knows the score. He can tell whether it's worth it or not."

So I hurried out to find Buddy and got him to go with me to look at it. Buddy gave the pawnshop man a hard time. "What's the matter with you, trying to cheat a young girl like this?" he said. "You can see she doesn't know anything about it. I'm a musician myself. I'm tellin' you this thing isn't worth any more than a hundred dollars."

The pawnbroker wouldn't go quite that far, but when Buddy showed him his union card he did knock fifty dollars off the price, so I got it for one hundred twenty-five dollars, and Ray gave me the money right away, like he'd promised he would.

I've never forgotten it, and, for that matter, I still have the sax, although I haven't tried to play it in a long time-which is a break for the neighbors. They're better off when I sing. I hope.

Being eighteen, I was able to play in the A.T.A. national women's singles in 1946; I was out of the girls' class. They played it at Wilberforce College in Ohio, and the A.T.A. paid my expenses out there and saw to it that I was put up in the college dormitory. I got to the finals and lost to Roumania Peters, a Tuskegee Institute teacher who was an experienced player; she had won the title in 1944.

It was my inexperience that lost the match for me. Roumania was an old hand at tournament play and she pulled all the tricks in the trade on me. I wasn't ready for it. But I didn't feel too bad. There was no disgrace connected with losing in the finals. I probably wouldn't have minded much at all if I hadn't felt so strongly that I had let Roumania "psych" me out of the match.

I was overconfident, there's no doubt about it, and she really worked on me. She won the first set, 6-4, and after I pulled out the second, 9-7, she began drooping around the court as though she was half dead.

She looked for all the world as though she was so exhausted, she couldn't stand up. Naturally, I thought I had it made.

It was quite a shock to me when Roumania managed to keep running long enough to win the third set, 6-3. It was also a good lesson for me. Unhappily, some of the A.T.A. people who had come out from New York were pretty disappointed in me. Maybe they thought they hadn't got their money's worth out of me because I had lost.

I remember one of them saying something to the effect that they were through with me, that they didn't think much of my attitude, and I know I was a pretty dejected kid for a while.

But I had played well enough, anyway, to attract the attention of two tennis playing doctors, Dr. Hubert A. Eaton of Wilmington, North Carolina, and Dr. Robert W. Johnson of Lynchburg, Virginia, nicknamed "Whirlwind," who were getting ready to change my whole life. They thought I was a good enough prospect to warrant special handling. I've often wondered if, even then, at that early stage of the game, they were thinking in terms of me someday playing at Forest Hills or Wimbledon.

Whether they were or weren't, they certainly were looking to the future. It was their idea that what I ought to do first was go to college, where I could get an education and improve my tennis at the same time.

"There are plenty of scholarships available for young people like you," Dr. Eaton told me. "It wouldn't be hard at all to get you fixed up at some place like Tuskegee." "That would be great," I told him, "except I never even been to high school."

That stopped them for a while, but the two doctors talked it over with some of the other A.T.A. people and decided that I was too good a tennis prospect to let go to waste. I suppose, now that I think hard on it, they already were hoping that I might just possibly turn out to be the black player they had been looking for to break into the major league of tennis and play in the white tournaments.

Although they never said so to me-not for a long time, the plan they finally came up with was for me to leave New York City and go to Wilmington to live with Dr. Eaton during the school year, go to high school there, and practice with him on his private backyard tennis court. In the summer I would live with Dr. Johnson in Lynchburg and I would travel with him in his car to play the tournament circuit.

Each doctor would take me into his family as his own child and take care of whatever expenses came up during the part of the year I was with him. It was an amazingly generous thing for them to want to do, and I know I can never repay them for what they did for me.

Not that it was an easy decision for me to make. I was a city kid and I liked city ways. How did I know what it would be like for me in a small town, especially in the South? I'd heard enough stories-to worry me.

Up north, the law may not exactly be on your side, but at least it isn't always against you just because of the color of your skin. I would have to go into this strange country, where, according to what I'd heard, terrible things were done to blacks just because they were black, and nobody was ever punished for them.

I wasn't at all sure going into something like that was a good idea. Harlem wasn't heaven but at least I knew I could take care of myself there. I might have turned down the whole thing if Edna and Sugar Ray hadn't insisted that I should go. "You'll never amount to anything just bangin' around from one job to another like you been doin'," Ray told me.

"No matter what you want to do, tennis or music or what, you'll be better at it if you get some education." In the end I decided he was right, and I wrote Dr. Eaton and told him I was coming. That was in August, 1946. He wrote me back and said I should get there by the first week in September. It didn't even leave me time to change my mind.