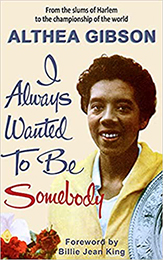

I Always Wanted To Be Somebody

Part 6

Althea Gibson

One of the high spots I am not likely ever to forget from my tennis career is my welcome home to New York a couple of days after I won at Wimbledon. I truthfully did not expect anything like what happened when I got off the airplane.

There was a crowd, including my mother and a city official who was representing Mayor Wagner, and a whole lot of newspaper, radio and television people.

They tell me my mother was one of the first people to get to the airport, and I know she was the first person I ran up to when I got off the airplane. I guess she cried a little, and I heard her telling the reporters, "I always knew Althea could do it."

I remember thinking I was glad she did because I hadn't always been so sure. But it made me feel good right down to the tips of my toes to see Mom so happy.

The Old Neighborhood

And a few hours later, when we got to 143rd Street, I saw that Daddy was taking it big, too, with all the people on the block standing on the sidewalk and him leaning out of the third-floor window and waving and hollering at me. It was a large day. It was hard not to think about other days on the same street, days when I felt as though I were carrying home a precious trophy if I had under my jacket a mushmelon that I'd snitched at the Terminal Market.

I was truly moved by the expressions on the faces of the people on the street. I won't ever forget being congratulated by Queen Elizabeth, but I am telling the plain truth when I say that it meant a lot to me to have all those people come out of their tired old apartment houses up and down 143rd Street to tell me how glad they were that one of the neighbors' children had gone out into the world and done something big.

The next day, the second day I was home, was another exciting one. The City of New York threw one of its traditional ticker-tape parades for me, from the Battery all the way up Broadway to City Hall, where Mayor Wagner was standing on the front steps waiting to give me the medallion of the city.

Forest Hills

But it wasn't long before I had to push all the Wimbledon glory and excitement into the back of my mind and start worrying about how I was going to do at Forest Hills. First, I went out to Chicago for the National Clay Courts tournament, which I won.

Then I set to work getting ready for the big one. I must admit I took time out to read some of the newspaper clippings Angela was good enough to send me from England, and one in particular, an editorial that appeared in the Evening Standard, made a lasting impression on me. It said, in part: "More than the Negro people should benefit from Miss Gibson's victory at a delicate period of racial emphasis in world affairs. It further underlines the willingness of the British to take to their hearts those of any race, creed or color. And it shows that somewhere in the great American dream there is a place for black as well as white."

That was nice to read, even the slightly scary part about the importance of my victory "at a delicate period of racial emphasis in world affairs." I couldn't help but wonder, my God, what am I supposed to be, a special assistant to the Secretary of State, or something?

But I made up my mind I wasn't going to dwell on what had happened already. I wanted with all my heart to become the champion of the United States, and that was the next order of business.

I stayed at the Vanderbilt Hotel on lower Park Avenue during the week of the Nationals. The Vanderbilt is famous as a tennis hotel, and a lot of the players were staying there. They even supplied a car to take us out to the stadium every day.

On the courts, everything went well for me. Of all people, I drew Karol Fageros as a first-round opponent. It was the second year in a row that I put Karol out of the tournament, and I was especially unhappy about being the cause of her going out in the very first round.

As a matter of fact, she almost put me out. She played beautifully, and each set was a real battle before I won, each time by the same score 6-4. I wanted badly to win, of course, but as I told Karol after the match, I had mixed emotions about it.

Comparatively Easy

After Karol, I had a comparatively easy time making my way through the draw to the finals. That first-round match was far and away my most difficult. I won from Elizabeth Lester, Sheila Armstrong, Mary Hawton and Dorothy Head Knode without losing a set. A sports magazine said I played as though I were serenely aware that I was the star. I don't know about that, but I do know I put everything I had into it.

I was confident that I would win but I was also worried that I might slip into overconfidence and blow my big chance. I didn't slip. It seemed almost fitting that the girl who fought her way through the other half of the draw to meet me in the final was Louise Brough, the former champion of the United States and three-time champion of Wimbledon.

Win or lose, I was going to play for the women's singles championship of the United States. I was already the No. 2 ranking woman player in the country, and if I could just win this one match, nothing under God's blue sky could keep me from being ranked No. 1.

That was really something. I was excited. I was confident, too. I don't mean that I wasn't nervous, because I was. But I was nervous and confident at the same time, nervous about going out there in front of all those people, with so much at stake, and confident that I was going to go out there and win.

I won fairly easily. Louise just didn't seem to have it my more. She tried hard, and she played fairly well in spots, but she no longer was the player who had outlasted me in a storm-postponed match way back in 1950. She had done well to play her way into the final. I beat her 6-3, 6-2, and the New York Herald Tribune said the next day, "there never was any doubt of the result."

I didn't very often try to hit the ball as hard as I can because I felt that it was smarter to let Louise make the errors, and that's pretty much the way it went. It was a marvelous feeling to see that last point go home and know that I had done it.

I wondered if the folks were watching on the television set back on 143rd Street. I shook hands with Louise, posed for a couple of dozen photographers, walked up in front of the marquee to accept my trophy from Vice President Richard Nixon, and talked endlessly to reporters before I went in to take my shower.

The most popular question seemed to be whether or not this victory was as exciting as winning at Wimbledon. I told them the simple truth. Winning at Wimbledon was wonderful, and it meant a lot to me. But there is nothing quite like winning the championship of your own country.

That's what counts the most with anybody. I don't think anything that has ever happened to me could match the feeling I got when I stood next to the Vice-President and made a little speech about how appreciative and humble and grateful I was for all the good fortune that had come my way, and then, as I stood there with my head bowed, still dripping wet with sweat from the hot match, I heard the volleys of applause beat down from the tiers of seats all around the beautiful old stadium.

That night we had dinner at Frank's Restaurant on 125th Street. That's the elite restaurant of Harlem, and I guess it must be one of the few restaurants in the world where almost all the customers are black and all the waiters are white. That, Frank says, is because he thinks there ought to be at least one place where a black man can have his meals served to him by a white man.