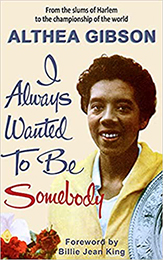

I Always Wanted To Be Somebody

Part 7

Althea Gibson

All of my problems weren't solved because I was the champion tennis player of the world after winning Wimbledon and Forrest Hills in the same year. Not by a long shot. I was only thirty years old and I had the best part of my life still to live.

I had to think about making enough money to support myself, about fitting myself, a black girl, into the larger world that I had come to know and to enjoy, and about whether or not I wanted to get married--and if I did, what was I going to do about it?

As far as making money was concerned, I had my mind pretty well made up. I might play professional tennis if a good opportunity presented itself, but I wouldn't become a professional unless I thought I saw a chance to make a lot of money. I didn't want to be a teaching pro all my life. I would rather remain an amateur, earn my living doing something else, and play tennis strictly for kicks.

Singing

Furthermore, I knew what that something else would be. It would be singing. I was very serious about it and I was sure of my ability to make the grade as a singer of popular songs.

Way back when I used to play hooky to hear the singers at the Apollo, I always had the ambition to be a singer myself when I grew up. I used to buy all the latest song sheets, learn the words by heart, then stand in front of a mirror for hours, practicing, expressions and all.

It wasn't hard at all for me to imagine that I was the new Ella Fitzgerald. Once, I think it was in 1943, I even got up the nerve to enter an amateur show at the Apollo.

I was dead serious about it. I even got my gang there to make sure I got my share of the applause. I won second prize and was supposed to get a week's engagement singing in the Apollo stage show, but the manager must have forgotten all about it because all I got was a ten dollar bill that he gave me on the show that night.

But I couldn't complain. That ten dollars bought a mess of fried chicken, collard greens and root beer. The saxophone that Sugar Ray bought me, and the band work I did while I was going to high school in Wilmington, sidetracked my singing interests for a while, but saxophone or no saxophone, I used to grab every chance I got to sing on stage in both high school and college.

I wanted to take music as a minor subject in college, but my faculty advisers talked me out of it. They said that being an athlete and a musician wouldn't mix. I think they were wrong.

Both Ways

It's funny, because later on, after I won at Wimbledon and Forest Hills, I had the same argument with my coach Sydney Llewellyn. Maybe I'm just stubborn but I didn't see any reason why I can't play tennis and work at being a singer, too. The one doesn't necessarily have to take away from the other.

For that matter, Sydney always has, in a friendly way, given me a hard time about my singing. I remember once we were at a party at the home of a friend of ours, and Sydney told me I couldn't sing my way out of a paper bag. "We've got a fellow right here at the party who can beat you singing," he said.

He meant Bill Davis. Well, I couldn't let a challenge like that go unanswered, so I agreed to sing a couple of songs, and have Bill sing a couple, and then let the guests at the party vote in which of us was the better singer.

Bill won the vote, and Sydney didn't let me forget it for a long time. It was my English friend Angela Buxton who helped me make my first serious singing effort. She knew how much I liked to sing and how serious I was about it, and in 1956 she arranged for me to make some test recordings in London.

One of her friends, Jerry Wayne, an English recording star, took charge of the session as a personal favor to Angela. Jerry not only set up and supervised the making of the records he even introduced me to Al Jackson, who is the oversea publicity representative for a lot of American musical performers, including Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington.

Everybody was as nice to me as they could be. But nothing ever happened with those records. I played them for all my friends when I got back home, but that was all. There was no crowd of agents, band leaders or A& R men knocking down my door trying to sign me to a contract.

Second Album

Any time I went to a tennis party, I was always asked to sing, and I always got a big hand, but that was still amateur night at the Apollo. When I finally managed to convince Sydney that working toward a singing career wouldn't necessarily wreck my tennis game, he made arrangements for me to study with Professor James Kennedy, who is the director of speech and voice at Long Island University.

Professor Kennedy gave me a lot of speech tests on tape, and then, in the late fall of 1957 and the spring of 1958, I began working with him three times a week in his office at the university. He was very encouraging, and helpful, and I began to feel that I might really have a chance of getting somewhere.

Then, to make things twice as exciting as they ever had been before, a member of the West Side Tennis Club, called to tell me that he was on the committee organizing a testimonial dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria for the Father of the Blues, W.C. Handy, the wonderful old man who had written "Memphis Blues," "Beale Street Blues," "St. Louis Blues" and so many other great songs.

They wanted to know if I would come to the dinner, and especially if I would sing a few songs as part of the program. I said I would be happy to, that I would be proud to be there.

Father of the Blues

With Professor Kennedy as my voice coach, I think I got by all right. I sang an obscure production number that Mr. Handy wrote way back in the twenties-it didn't even have a title-and I think he got a kick out of it. I know I did.

I'll always remember standing on the dais in the grand ballroom of the Waldorf that night, singing that great man's music to him while he sat there, blind and weak and old but still cheerful and still interested and still very much with the beat, listening intently and applauding softly when I finished.

Mr. Handy only lived a couple of months after that night. I like to think that he had a good time at his dinner. As so often happens when you are doing something with an unselfish motive, and glad to do it, I got a good break for myself the night of the Handy dinner.

Among the people I met was Henry Onorati, the vice-president of Dot Records, who invited me to make some test records with an eye toward recording an album of popular ballads. I did, and we did.

The album was released in May, 1958, and my professional singing career was officially launched when Ed Sullivan asked me to sing on his Sunday night television program the same week. Of course, I couldn't be sure whether the Sullivan invitation came because I was a good singer or a good tennis player.

But either way, I'd been getting a chance to learn something about singing, and I couldn't ask for anything more. I figure it's much the same as it is in tennis--you have to be a little bit lucky to get your big chance, but once you get it, you're entirely on your own and you had better put everything you've got into it.

Me being that kind of never-say-die competitor, I couldn't resist saying to Sydney, who was standing in the wings waiting for me as I came offstage after singing that night on the Sullivan show, "What was that you said about me not being able to sing my way out of a paper bag?"

Actually, I have no burning desire to set the world on fire as a singer or, for that matter, as anything else. I felt that I'd established myself as a person, that I've made a place for myself in the world, and I was happy. I didn't feel I was missing out on anything.

All the good things, I was sure, will come in time. Even a man. I admit I thought a lot about getting married.

A Man?

Of course, having spent almost all of my grown up life concentrating on playing tennis, with very little time left over for socializing, I was no authority on the boy girl bit. For instance, the only reaction I had the one time I was proposed to was puzzlement.

The man said to me that he thought it would be a good idea for us to get married, and even though he seemed to be in dead earnest about it, I just couldn't take it that way. He didn't give me a ring or do anything except simply suggest that we get married, and I couldn't help but think, isn't something supposed to happen?

Anyway, one thing I was sure of is that I was not going to throw away whatever chance I have of doing something with the success I've been able to achieve. I was not about to throw away everything for love.

I could do without a man if I had to. I'd done it for fifteen years. I didn't feel I was missing out on anything, really. All the good things would come, like I said, even though it might take a little time.

For that matter, you can enjoy yourself being single. You don't have to tie yourself down. Sure, it can be lonesome sometimes, but it has its compensations. You can work out the kind of schedule that suits you best, without worrying how it might affect somebody else, and you can make the most of the pleasures that are most meaningful to you--like, in my case, playing tennis, singing, listening to records, watching television, going to the movies, and seeing my family and friends.

The people who came up with you and struggled with you are the ones you turn to when you need somebody. Take it from me, when you have a friend you have a gold mine. As far as the color question is concerned, I had no feeling of exclusion anymore. At least, I didn't feel I was being excluded from anything that mattered.

Maybe I couldn't stay overnight at a good hotel in Columbia, South Carolina, or play a tennis match against a white opponent in the sovereign state of Louisiana, which had a law against such a social outrage, but I can get along without sleeping at the Wade Hampton and I don't care if I never set foot in Louisiana.

There is, I have found out, a whole lot of world outside Louisiana--and that goes for South Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama, and all the other places where they haven't gotten the message yet. Actually, I think there has been a lot of good will be shown on both sides lately, and I think we're making progress.

The Race Thing

I am not a racially conscious person. I don't want to be. I see myself as just an individual. I can't help or change my color anyway, so why should I make a big deal out of it? I don't like to exploit it or make it the big thing.

I'm a tennis player, not a black tennis player. I have never set myself up as a champion of my race. Someone once wrote that the difference between me and Jackie Robinson was that he thrived on his role as a black battling for equality whereas I shied away from it.

That man read me correctly. I shied away from it because it would be dishonest of me to pretend to a feeling I don't possess. There doesn't seem to be much question that Jackie always saw his baseball success as a step forward for black people, and he aggressively fought to make his ability pay off in social advances as well as fat paychecks.

I'm not insensitive to the great value to our people of what Jackie did. If he hadn't paved the way, I probably never would have got my chance. But I had to do it my way. I tried not to flaunt my success as a black success.

It's all right for others to make a fuss over my role as a trail blazer, and, of course, I realize its importance to others as well as to myself, but I can't do it. It's important, I think, to point out in this connection that there are those among my people who don't agree with my reasoning.

A lot of those who disagree with me are members of the black press, and they beat my brains out regularly. I have always enjoyed a good press among the regular American newspapers and magazines, but I am uncomfortably close to being Public Enemy No. 1 to some sections of the black press.

I have, they have said, an unbecoming attitude. They say I'm bigheaded, uppity, ungrateful, and a few other uncomplimentary things. I don't think any white writer ever has said anything like that about me, but quite a few black writers have, and I think the down-deep reason for it is that they resent my refusal to tum my tennis achievements into a rousing crusade for racial equality, brass band, seventy-six trombones, and all. I won't do it.

I feel strongly that I can do more good my way than I could by militant crusading. I want my success to speak for itself as an advertisement for my race. For one thing, I modestly hope that the way I have conducted myself in tennis has met with sufficient approval and good will to assure that the way will not close behind me.

I feel sure that that will be the case: this isn't, I'm convinced, a one-shot proposition. Any other black man or woman with the ability to compete on the national tournament level will get a fair chance.

The U.S.L.T.A. worked closely with the A.T.A. in examining the qualifications of black players, and, in effect, any player strongly recommended by the A.T.A. for a place in the national championship draw is accepted without question. The A.T.A., of course, is careful not to recommend any but fine players, which is as it should be.

Eventually, I hope, our players will be able to earn their places in the draw the same way the white players do, by competing in all the recognized tournaments that lead up to the national championships. Meanwhile, it is heart-warming to me to see as many as half a dozen black men playing at Forest Hills, as was the case in 1957.

Their presence there, I feel, was the best answer I could possibly make to the people who criticized me for failing to do as much as they think I might do to help my people move forward. Trying to be objective about it, I suppose some reporters might feel that I'm a cold sort of person.

Even my friend Angela Buxton once wrote in a magazine article that when she first met me she thought me "cold, unapproachable, assertive and domineering." And Sydney Llewellyn, the person closest to me of anybody outside my family, once told a reporter, "The only trouble with Althea is that she doesn't mind hurting people."

With this kind of testimony staring me in the face, I have to concede that I don't always charm everybody I meet. The reason, I think, without being psycho-analytical about it, goes back to my childhood.

I grew up a loner, suspicious, withdrawn, slow to like people, wary about trusting any part of myself to anyone else. It isn't easy to change your personality.

I still keep to myself and I know I hold back until I'm as sure as I can be that it's safe to let down the barrier. I'm not a cold person, underneath. But I'm afraid sometimes I appear to be.

It just goes to show you that you shouldn't judge a book by its cover. First impressions aren't always true ones.