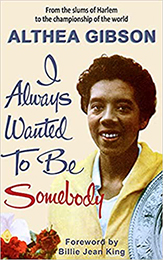

I Always Wanted To Be Somebody

Part 8

Althea Gibson

These days, my life consists mostly of a series of tournament tours, involving pretty much the same routine no matter where I go. Between trips—each trip usually includes a number of tournaments—I may have anywhere from a week to a month at home, during which I try desperately to catch up on all my other responsibilities, from answering mail and visiting my family to taking singing lessons and going on furniture hunting expeditions.

The tournaments not only are the amateur tennis player's way of working at his trade (I know I shouldn't call it that because we don't make any money out of it), but they also provide us with one of our greatest rewards, the opportunity to see the world, meet a lot of interesting and often famous people, and enjoy a style of living to which most of us distinctly were not accustomed before we got into tennis.

Take, for instance, my South American-Caribbean trip in March, 1958. It was a part of the world I had never seen, and I was sure it would be an exciting trip.

Eddie Herr, who runs the Good Neighbor tournament in Miami every year, sent me a list of the scheduled South American and Caribbean tournaments, and I picked out five that I would like to enter. That's the best part about being an internationally ranked amateur tennis player; it's the next best thing to having a travel agency send you a whole bunch of colorful brochures and invite you to pick whatever trips you would like to make, free.

My coach Sydney drove me to the airport on the morning of March 1, and I flew from New York to Montego Bay, Jamaica. It's a beautiful city, and I had a fine week there.

The tournament started the day I arrived, but I had drawn a first-round bye and didn't have to play my first match until the next day. It was so hot that none of the matches began before two o'clock in the afternoon, when the breeze cooled things off somewhat, and they usually kept playing right into the evening, finishing up under lights if necessary.

As a matter of fact, my first match was played entirely under the lights, and I liked it very much. It was cool, the lighting was excellent, and the ball wasn't at all hard to follow.

Except for the time you spend on the court, you don't wear yourself out when you go to these tournaments. We were mostly content to live the good life sleeping late in the morning, with a late breakfast taking a swim in the hotel pool, sunbathing for a while, then going to the club for lunch and the matches.

We almost always stayed at the club for dinner, and then by the time we got back to the hotel it was time to go to bed, unless you were lucky enough to have a date. At Barranquilla, as at almost every tennis tournament, there was one gala social function during the week, a reception and dance for the players, club officials, and local big shots.

Other than that, things were very quiet. I should add that the tournament was less placid than the social life—for me, anyway. Young Janet Hopps of Seattle, Washington put me out in the semi-finals of the singles 3-6, 6-3, 7-5 after I had built up a 5-3 lead in the second set and needed only one game to close out the match.

I had a little better luck in the doubles. I played with my old traveling companion Karol Fageros and we beat Maria Bueno of Brazil and Lois Felix, a Connecticut girl, in the final.

From Barranquilla I flew to Caracas. I had much more fun there, as far as the tennis was concerned. I won the singles by beating Maria Bueno in the final, and Karol and I won the doubles again, this time from Maria and Janet Hopps.

I really had to work for that singles win, though. Anybody who thinks tennis players just coast on these wintertime tours should have seen me sweating out that match. Maria, the Brazilian girl they call "The Little Saber," was very much on her game, and she gave the big crowd, which quite naturally was rooting hard for her (inasmuch as she was not only the underdog but also a South American and therefore one of their own), all the excitement they had hoped for.

I won the first set easily enough at 6-1, but then, in the second set, I fell behind, 5-4, with my own service coming up. Serving is one of my strong points, but this time I served badly.

I suppose the ecstatic shrieks of the crowd on every point Maria won might have made me press too hard. Whatever it was, Maria put away the first two points of that tenth game for outright winner, and finally, at 15-40, I committed the unpardonable sin of double-faulting on set point.

That evened the match and we went off the court for a ten-minute rest period. Winning that second set had steamed up Maria's fighting spirit, and she kept the pressure on me all the way through the third set before I finally broke her service at 7-all and went on to win 9-7.

I felt that I had really earned that one. The highlight of the trip was an excursion set up by the tournament committee to a magnificent resort hotel located some four thousand feet above the city, which itself is three thousand feet above sea level.

It's accessible only by cable cars, which go right up the side of the perilously steep mountains. We were all a little skeptical when we were put in the car, which holds twelve or fourteen people; you feel as though you're just suspended in space, and you can't help wondering if the cable is going to bold up.

But we made it safely, and we really enjoyed the visit. The hotel had a skating rink, swimming pool, observation tower, and all sorts of handsome dining and entertainment rooms. We were amazed when they told us that there were only seven couples registered in the whole hotel that day. Maybe it's a little too remote, and undoubtedly a lot too expensive, to attract larger numbers of people.

One thing that happened to me on this part of the tour served to convince me that I hadn't lost my old touch when it came to relations with the opposite sex. There was this Venezuelan tennis player whom I had noticed playing doubles a couple of times, and there was something about him that I instinctively liked.

Also, I was lonely. You can get very lonesome when you're traveling around like that, especially when there is nobody in the company to whom you feel close. So I made it my business to speak to him; I even invited him to have a drink with me.

And while we were sitting there, talking about tennis and about places we had been and people we knew, I blurted it right out that I liked him every much. I must say he took it calmly. In fact, he took a sip from his drink and looked at me kind of speculatively across the top of his glass and said, well, that was very interesting and certainly very flattering to him, and he would think hard on it and let me know.

He didn't say what he would let me know, and I didn't ask. But I was already wishing I hadn't broken my firm rule against having anything to do in a romantic way with another tennis player.

I've seen so much careless swapping of partners among the tennis crowd that I've always sworn that was one trap I would never fall into. I'd rather kill an afternoon in the movies any time. But here I had gone and done it—well, I hadn't really done anything, but I had left myself wide open to this fellow and I was as vulnerable as hell.

I regretted it. I regretted it a whole lot more the next day when he came up to me and said that he had thought about what I had said and he was sorry but he didn't think he was going to be in a position to do anything about it.

For crying out loud, all I'd done was tell him I liked him. I felt like a fool. I don't think I'll ever do anything like that again.

Our next stop was San Juan, where I stayed at the Caribe Hilton and loved every minute of it. That was really it. In the first place, it's an ideal spot for a tennis tournament because the hotel, tennis courts, swimming pool, and beach are all located right on the same grounds, and what more could anybody ask for?

As I told the people there, I would like to be invited back every year; they'll never have to coax me, that's for sure. The only thing I was sorry about was that I didn't play better in the final, which I lost to Beverly Baker Fleitz, the California girl with the two forehands. Beverly is ambidextrous, and good. I started out by staying in the backcourt against her, figuring that I would let her come to the net and then pass her. But Bev got away to a quick 3-0 lead and I changed my mind in hurry and reverted to my usual pattern of following my service in to the net and looking for the kill shot.

Unluckily for me, that didn't work any better, and in the end I wound up playing mostly defensive tennis, which is emphatically not my cup of tea, and losing 6-4, 10-8. I never like to lose but I was especially unhappy about this one because Bill Harris, the chairman of the tournament committee, and Welby Van Horn, the Caribe Hilton professional, had done so much for all of us players that I wanted to put on the very best show I could for them.

I'm sure the gallery enjoyed the match, however. They gave Bev a noisy band when she put away the last point. And all I could do was tell myself ruefully that you can't win them all.

One of the unusual things about the Caribe Hilton tournament is that the tennis players, who are popularly supposed to be terrifically tight with their own money and free only with other people's, got together and threw a cocktail party for Harris and Van Horn and the other members of the committee, just to show their appreciation for the wonderful time they had had.

I don't think I ever heard of that being done before, but I think it was a fine idea. Incidentally, although I was the only black guest at the Caribe Hilton during the time of my stay, I couldn't possibly have been treated more cordially or with more consideration.

Along with the other players, I was allotted cabana space on the ultra-exclusive Caribe Hilton beach, and I couldn't have lived it up any more if I had been a millionaire in my own right. A millionaire with a white skin, at that. Speaking of money, I ought to spell out the way an amateur tennis player deals with the financial problem on tour.

As I said, the airplane tickets, calling for first-class passage and including meals, were mailed to me at home. Then, as I checked in at each tournament, I was given a cash expense allowance, conforming with international regulations, to pay for my hotel room, laundry and cleaning, tips (which are a major item for traveling tennis players, including, as they must, service personnel at both the hotel and the tennis club), and other incidentals.

We can sign for our meals, but if we want a drink or a package of cigarettes we have to pay cash. We have to pay cash for taxicabs and telephone calls and a lot of other small items that have an unpleasant habit of adding up.

There has been, in the last year, agitation to reduce the daily expense allowance for a touring player, and I believe the figure of eleven dollars and twenty cents was mentioned as a sensible sum.

There I wouldn't be anything sensible about it at all. How would you like to be trying to live in a strange city, putting up at a fairly decent hotel, and paying all the different charges I've mentioned, on eleven dollars and twenty cents a day?

There aren't many cities left on the tennis circuit, in any country, where the cheapest room in any respectable hotel can be had for less than seven or eight dollars a day, and more often than not you've got to pay ten or twelve dollars and like it.

If you were operating on eleven dollars a day you would be in the red before you even got started. Some people persist in the scandalous belief that tennis players clean up financially.

The only ones, to my knowledge, who do are the ones who play on Jack Kramer's professional tour, or perhaps a few amateurs who are blessed with extraordinary talents for manipulating dice or cards or for judging the comparative speed of race horses. It would take a true financial genius to make a stake on a tennis player's expense account.

The expensive living I enjoy on the tournament circuit disappears in a hurry when I get back home. I can't afford it. I do have a nice place of my own now, in an apartment building on Central Park West—the back of the building faces Harlem and the front overlooks the beautiful green grass and wide open spaces of Central Park, which I think is a nice touch—but I don't have much furniture in it yet and I have to be real chinchy about things like food, entertaining, and recreation.

I save a little money, but very little, from my expense allowances and the seventy-five dollars a month I earn from my job as a consultant to the Harry C. Lee sporting goods company. My singing has now begun to bring in a little money, and what with one thing and another I manage to get by.

But I'm an expert at making a dollar stretch. My tennis trophies and other trophies like the Didrikson Zaharias Trophy which I won for being picked as the Woman Athlete of the Year for 1957, take up a lot of space in the apartment and make up in a way for the scarcity of furniture, but most of them are still in boxes. I don't dare take them all out because if I did I wouldn't have time to do anything but polish them.

I've got enough cups and plaques and statuettes to fill a corner of a warehouse, and I've also got some handsome and useful things like tea sets, butter dishes, cake plates, cocktail shakers, chafing dishes, serving trays, and what not. I'm a guaranteed lifetime customer for the silver-polish industry.

Come to think of it, I'll also have to keep a little gold polish on hand. My Wimbledon trophies are beautiful gold silvers, and I am very proud of them and I intend to keep them shining. Of course, I hope to add some more trophies to my collection before I am through, maybe some more amateur ones and maybe some professional ones, too.