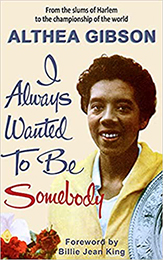

I Always Wanted To Be Somebody

Part 9

Althea Gibson

One thing about the life of a tennis champion; you never can rest on your victories, unless you retire, and I'm not ready to retire yet. With my coach Sydney Llewellyn working along with me, I will keep going right back into training as each new season approaches, just as I did when I got back from the Caribbean and began promptly to prepare for the 1958 Wimbledon and United States championships.

I knew I wasn't going beat anybody with my reputation or my newspaper clippings. I would have to beat them all on the tennis court. If I ever showed signs of forgetting that, Sydney was right there to remind me.

Sydney is not only a fine teacher of tennis, including both strokes and tactics, he is also something of a psychologist. He keeps after me all the time.

First, he pounded to make me think and act and play with the idea in mind that I had what it takes to become the champion. And after I made it, instead of letting up, he pressed me all the more.

"You've got to hit that ball with all your strength and attack forcefully, and overpower your opponent. You've got to hit with pace and with depth, and put that championship power and determination pride behind every shot. Never let up, and don't every change from the championship way of hitting.

"You were hitting the daylights out of the ball last year. You were hitting it with force. You've got to hit it even more forcefully, you've got to hit it with daring.

"You're the champ, you can take chances, you can hit all out on every shot. You've got the ability and you've got the experience and you've got the control and the power. All you have to do is use it.

"Stand up there and swing freely and hit with force. Absolutely defy the ball to go anywhere except where you want it to go. That ball isn't going to talk back to you. "You're its master. It is, you see, Sydney's idea that I should fill my mind with positive thoughts and give no room at all to negative thoughts, to doubts or fears.

"You're going to win" is the only attitude he will countenance. "You're going to hit with force, as forcefully as you can, and never let up and you're going to hit the ball long, with the kind of depth that keeps your opponent back on her heels on the defensive, just like in a prize fight, then you're going to open up the court with a forcing shot and then your power is going to take advantage of that opening and put the ball away, and you're going to still be the champion because you're going to play like a champion."

He psychologizes me, there's no doubt about it. But I like it. It keeps me on my toes. It reminds me that I can't coast, that I mustn't take anything for granted, that I can't give away any games or even points, that I must play power tennis all the time because that's my game and that's what made me the champion.

The subconscious mind acts as a private tape recorder, Sydney says, and then, in a time of crisis, when you're out there all alone on the court and the championship is going to be won or lost in a few swift exchanges of shots, you play these thoughts back to yourself and they mean something to you and you respond to them and they become part of the attacking force you muster and they help you beat back your challenger because that's the way a champion does.

If you have negative thoughts on your private tape recorder, those are the ones that come through at the time of crisis, and they defeat you. Sydney has something there. He cites, as an example the night I left Forest Hills back in 1950 leading Louise Brough 7-6 in that celebrated third set.

Rhoda Smith took me home with her and patted me on the back all the way, and in her apartment that night she wouldn't let anybody talk to me about the match. "Even if you lose. tomorrow, honey," she told me "it won't make a particle of difference. You did yourself proud already."

She meant well, of course. She wanted to ease my mind and relax me and turn away the tension. But Sydney says she did exactly the wrong thing, and I believe he's right. Somebody, Sydney says, should have been talking to me like this: "You were hitting a great tennis ball out there today. You were hitting the ball with pace, and you were hitting it long. You showed Brough more raw power than she's ever seen come off a woman's racket.

"You had her on the run. You're going to beat her tomorrow you're going to finish her off, because you're going to go right out there and do it again. You've got nothing to lose and she's got everything to lose, and you're going to walk out there and tee off with all your strength and power, and she's going to have to play it safe and hope she gets it back and hope you miss and make errors.

"But you won't. You'll hit the way you hit today, and you'll win, and you'll be on your way to the championship."

I forced myself to keep those words of Sydney's in my mind every minute when I went back to London for the 1958 Wimbledon tournament. Winning that one meant a whole lot to me. Not only would the championship be an important asset to me whether I became a professional tennis player or a singer, or both, but there was a question of pride involved too.

In sports, you simply aren't considered a real champion until you have defended your title successfully. Winning it once can be a fluke; winning it twice proves that you are the best. I was passionately determined that there wasn't going to be any "one-shot" tarnish on my Wimbledon championship.

They made me the favorite to win the tournament but there certainly were plenty of people who weren't sure that I would—partly, I think, because I hadn't looked too good losing some matches on my Caribbean tour and partly because I lost to Christie Truman in one of my two singles matches in the Wightman Cup play that preceded Wimbledon. But I knew what they didn't know, that I had experimented with my game in some of those matches, trying to find out what I could do as a back-court player, letting the other girl take over the net, where I usually station myself throughout most of the match.

Because I'm strictly an attacking player, serving hard and running to the net and putting away the volley, I didn't do very well in the back court. But I did sharpen my ground strokes and improve my passing shots, and I think the experience did me more good than harm, although I was miserable about our losing the Wightman Cup to the English girls, 3-2.

When Sydney and I had our last talks before I flew to England, there was no doubt in our minds that l would stick religiously to my tried and true serve-and-run-to-the-net tactics at Wimbledon. That's what I did, and the results were all that we had hoped they would be. I had only one hard match in the whole tournament, against Shirley Bloomer, the No. 1 ranked British player, in the quarter-finals.

Shirley won the second set after I had won the first, and she had me down 2-0 in the third set before I got the grease going in the frying pan and ran off six games in a row for the match, 6-3, 6-8, 6-2.

The set Shirley took from me was the only one I lost in the whole tournament. I beat Ann Haydon 6—2, 6—0 in a semi-final match that took only thirty-one minutes to play, and then I won from Angela Mortimer 8-6, 6-2 in the final.

It was a wonderful feeling to know that I was not only still the champion, but, even more important, was clearly the champion, even in the minds of those who had chosen to doubt me after my first victory at Wimbledon in 1957.

I felt that I had answered the big question. Eleven foot faults were called against me in the first set with Angela and at one point Angela had me down 5-3 and at set point. But I managed to pull it out with a few hard service aces, and things went much better in the second set.

I didn't want any bad feeling between us. I won, and that was all that mattered. The Duchess of Kent did the presentation honors from the Royal Box this time, and I danced at the Wimbledon Ball with another Australian, Ashley Cooper, who had succeeded Lew Hoad as the men's singles champion.

I didn't know if I would ever dance at another Wimbledon Ball, so I stayed up late and enjoyed this one to the fullest. It was nice to be the champion; I'm not ashamed to admit I liked it. Between tournaments now I go to see my family and friends, and I still spend a lot of time in the movies.

There would be no hard times in Hollywood if there were more people like me around. I would like to find out about the legitimate theater but that's one of the things that will have to wait until I have a steady income.

I've been exposed to it once. Sarah Palfrey took Sydney and me to dinner at Sardi's and then to see Lena Horne in Jamaica. It's the only stage play I've ever seen.

I keep busy around the apartment. For one thing, I'm pretty mechanically minded and I get a kick out of putting in plugs and fixing broken fixtures and things like that. If there's anything around the house that needs fixing, I always try it myself before I call up somebody else to do it. I've always been that way.

You can see that my pleasures and interests are simple. I have no lofty, overpowering ambition. All I want is to be able to play tennis, sing, sleep peacefully, have three square meals a day, a regular income, and no worries. I don't feel any need to be a King Midas with a whole string of people hanging on me to be supported.

I don't want to be put on a pedestal. I just want to be reasonably successful and live a normal life with all the conveniences to make it so. I think I've already got the main thing I've always wanted, which is to be somebody, to have identity. I'm Althea Gibson, the tennis champion.