Althea

A Post Script

John Yandell

At the conclusion of our amazing series on Althea Gibson, based on her autobiography I Always Wanted To Be Someone, Althea had just defended her Wimbledon singles title in 1958. But her narration of her own story ends there.

What happened next? And in the rest of her life?

After Wimbledon she went on to defend her U.S. Nationals title. She finished with 11 Grand Slam titles, 5 in singles and 5 in doubles and one in mixed.

Let's remember that she never was even allowed into a Grand Slam until she was 23. Contrast that with Maria Sharapova and Serena Williams both of whom had already won a Slam at age 17.

So where does Althea stand in tennis history? "She is one of the greatest players who ever lived," said Bob Ryland, a tennis contemporary, the first black player ever to play professional tennis, and a former coach of Venus and Serena Williams. "Martina Navratilova couldn't touch her. I think she'd beat the Williams sisters."

Finances

And where did all that success leave her financially? "The truth, to put it bluntly, is that my finances were in heartbreaking shape," she said. "Being the Queen of Tennis is all well and good, but you can't eat a crown. Nor can you send the Internal Revenue Service a throne clipped to their tax forms. The landlord and grocer and tax collector are funny that way: they like cold cash."

Althea concluded that “I reign over an empty bank account, and I'm not going to fill it by playing amateur tennis." Professional tours for women were still 15 years away, so her opportunities in tennis were largely limited to promotional events.

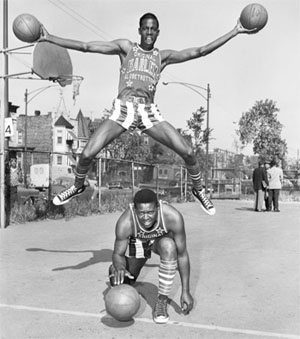

In 1959 she signed to play a series of exhibition matches before Harlem Globetrotter basketball games. She won the singles and doubles titles at the Pepsi Cola World Pro Tennis Championships in Cleveland, but received only $500 in prize money.

She also tried playing on the women's professional golf tour. Many hotels still excluded people of color, and country club officials throughout the south—and some in the north—routinely refused to allow her to compete. When she did compete, she was often forced to dress for tournaments in her car because she was banned from the clubhouse. Her lifetime earnings were less than $25,000.

"When I looked around me, I saw that white tennis players, some of whom I had thrashed on the court, were picking up offers and invitations," she said. "Suddenly it dawned on me that my triumphs had not destroyed the racial barriers once and for all, as I had—perhaps naively—hoped."

She repeatedly applied for membership in the All-England Club, based on her status as a Wimbledon champion, but was never accepted. Her doubles partner, Angela Buxton, who was Jewish, was also repeatedly denied membership.

In 1968, with the advent of Open tennis, Gibson tried to repeat her past success. But at age 40, she wasn't able to win many matches.

During this same period, Althea also pursued her long-held aspirations in the entertainment industry, as we saw in previous articles. But record sales were disappointing.

She was a celebrity guest on the TV panel show What's My Line? She was cast as an enslaved woman in the John Ford motion picture The Horse Soldiers (1959), which was notable for her refusal to speak in the stereotypic "Negro" dialect mandated by the script. She also worked as a sports commentator, appeared in print and television advertisements for various products, and increased her involvement in social issues and community activities.

In 1976, at the age of 49, Gibson made it to the finals of the ABC television program Superstars, finishing first in basketball shooting and bowling, and runner-up in softball throwing. She attempted a golf comeback, in 1987 at age 60, with the goal of becoming the oldest active tour player, but was unable to regain her tour card.

In a second memoir, So Much to Live For, she articulated her disappointments, including her unfulfilled aspirations, the paucity of endorsements and other professional opportunities, and the many obstacles of all sorts that were thrown in her path over the years.

In 1972 she began running a national mobile tennis project, which brought portable nets and other equipment to underprivileged areas in major cities. She ran multiple other clinics and tennis outreach programs over the next three decades.

She coached numerous rising competitors, including Leslie Allen and Zina Garrison. "She pushed me as if I were a pro, not a junior," wrote Garrison in her 2001 memoir. "I owe the opportunity I received to her."

In the early 1970s, Gibson began directing women's sports and recreation for the Essex County Parks Commission in New Jersey. In 1976 she was appointed New Jersey's athletic commissioner, the first woman in the country to hold such a role, but resigned after one year due to lack of autonomy, budgetary oversight, and adequate funding. "I don't wish to be a figurehead", she said at the time.

In 1977 she challenged incumbent Essex County New Jersey State Senator Frank J. Dodd in the Democratic primary for his seat. She came in second behind Dodd, but ahead of Assemblyman Eldridge Hawkins.

Gibson then went on to manage the Department of Recreation in East Orange, New Jersey. She also served on the State Athletic Control Board and became supervisor of the Governor's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports.

Marriages

She married her best friend Rosemary Darben's brother William in 1965. His income helped supplement the proceeds she received through various sponsorship deals. But the marriage ended in 1976. In 1983 she married her old tennis coach Sydney Llewellyn. That marriage also ended in divorce. She had no children.

In the late 1980s Gibson suffered two cerebral hemorrhages, followed by a stroke in 1992. Ongoing medical expenses left her in dire financial circumstances.

She reached out to multiple tennis organizations requesting help, but none responded. Former doubles partner Angela Buxton made Gibson's plight known to the tennis community, and raised nearly $1 million in donations from around the world.

Gibson survived a heart attack in 2003, but died on September 28 that year from complications following respiratory and bladder infections.

43 Years

It would be 15 years before another non-White woman—Evonne Goolagong--won a Grand Slam championship in 1971, and 43 years before another African American woman, Serena Williams, won her first of six US Opens in 1999, not long after faxing a letter and list of questions to Gibson. Serena's sister Venus then won back-to-back titles at Wimbledon and the US Open in 2000 and 2001, repeating Gibson's accomplishment of 1957 and 1958.

On opening night of the 2007 US Open, the 50th anniversary of her first victory at its predecessor, the US National Championships, Gibson was inducted into the US Open Court of Champions. "It was the quiet dignity with which Althea carried herself during the turbulent days of the 1950s that was truly remarkable," said then USTA president Alan Schwartz at the ceremony.

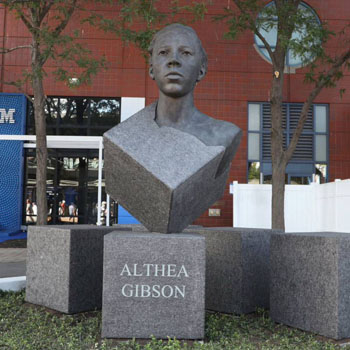

In 2018, the USTA unanimously voted to erect a statue honoring Gibson at Flushing Meadows, site of the US Open. The statue, created by sculptor Eric Goulder, was unveiled in 2019.

In her 1958 retirement speech Althea had said "I hope that I have accomplished just one thing, that I have been a credit to tennis, and to my country." That statement is inscribed on a plaque near the statue.