Pancho Segura:

The Beginning

Caroline Seebohm

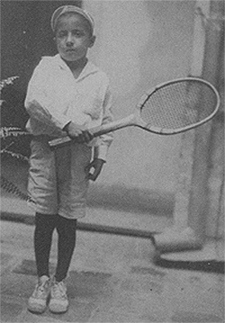

Nobody noticed the small dark skinned boy in a corner of the Guayaquil Tennis Club, hitting ball after ball against the wall with a dilapidated looking tennis racket. The boy was alarmingly thin, with bandy, skinny legs that curved in like bananas, and slender arms with fragile wrists, so fragile that in order to stroke the ball hard enough for it to bounce back from the wall, he had to keep both hands on the handle of the racket.

To the few members of the club who might have glanced at him as they left the court and prepared to go back to their expensive homes for a shower and a drink, he was just another poor little kid from the barrio who was passing the time while waiting for somebody to take him home.

Fierce Child

They would have been mistaken, and if they had paused to look at the little boy more carefully, they might have realized their mistake. For the child's expression was one of fierce concentration and focus.

He was not just passing the time. He was practicing hitting tennis balls the only way he knew how-by doing it over and over again with a passion that belied his young age. What was reflected in that boy's eager, intent face was what audiences all over the world would come to know and thrill to one day.

As it grew dark at the club and long shadows made it difficult for the boy to see the ball anymore, a tall, strongly built man came from the courts where he had been tidying up, collecting towels and balls, unwinding the nets, locking doors, and closing up the club. "Panchito, let's go home."

Reluctantly, the boy stopped his hitting, picked up the ball he had been playing with, gave it to his father, and took his hand. It was time for Domingo and Pancho Segura Cano to go home.

Francisco Segura Cano (Cano was his mother's name, commonly used as the family name in Latin American countries) was about seven years old when he first picked up a tennis racket. By this time he had already been through illnesses and hardships that might have deterred a less determined character.

He was born on June 20, 1921, on a bus in Ecuador traveling from Quevedo to Guayaquil. "The roads at that time were in bad condition," remembered Francisca Cano de Segura, Pancho’s mother. "We had gone a short way when I had to ask my husband to ask the bus driver, as a favor, to return to Quevedo because I was going to give birth prematurely." Thus "the little dark one," as his mother called him, entered the world.

He was the firstborn son of Domingo Segura Paredes and Francisca Cano. His father was Spanish in origin, his mother an Indian from Quevedo, so their son was a cholo, of mixed blood. He was born in June, which in some parts of the world is a lovely month, with clear blue skies and gardens in bloom.

Guayaquill

In Guayaquil it is wretchedly hot and only a little less humid than in the officially rainy months, December through April. From his very first moments, Pancho, like everyone else in Guayaquil, had to learn to accommodate to the heavy, sticky, mosquito infested air of his native city.

Guayaquil was then a modest commercial city of roughly 250,000 people, located in a sweltering region of the southern coast not far from the Peruvian border. In those days it had a third world look, with small wooden houses with corrugated iron roofs, dusty streets with horses and carts, very few cars, and untended vegetation.

After a devastating series of fires, most of the new houses built in the city were built of cement. Its primary source of employment was the port, which was the major shipping entry into Ecuador through the El Salado estuary, transporting cargo in and out of this small South American country nestled in the Andes. The Guayas River delta is the largest in the southern Pacific Ocean, and the maritime port still handles three-quarters of the country's imports and almost half of its ex- ports.

Most of the inhabitants of Guayaquil who made money in those years had import-export businesses, trading in coffee and bananas. They lived in large houses to the north of the city, surrounded by high walls and flowering trees, and belonged to the Union Club, with its fine view of the waterfront.

It was gentlemen like these who founded the first Guayaquil Tennis Club in 1910. Apart from the fine houses owned by the rich, perhaps the most compelling aspect of Guayaquil was--and still is--its cemetery.

Positioned on a hill above the city, it is the place where for well over a century hundreds of thousands of citizens have been laid to rest.

The grand residents of the town are buried in an extended plateau within the city's gates at the bottom of the hill, where the imposing mausoleums, handsome statuary, and sculptures.

Rising up the hill in an increasingly crowded jumble, the cemetery becomes more democratic inhabited by the local dead, a mass of disorderly, crumbling, packed-together crosses and shrines, almost uniformly painted white, with black inscriptions. Pancho Segura's parents are buried there.

Pancho was the first of seven children born to Domingo and Francisca. Two more boys and four girls came later, There was also a daughter from Domingo’s first marriage.

Nothing came easily to them. But the eldest son, Francisco, had the most difficult challenges. His childhood was riddled with sickness. The first major illness he suffered was a double hernia, an affliction fairly common in baby boys.

A pediatric hernia is related to the development and descent of the testes and causes acute swelling and pain in the groin. It is likely that Pancho’s parents did not immediately recognize the problem, and allowed it to go untreated.

By the age of ten, Pancho remembered being almost unable to walk, the pain and swelling were so great. He was finally operated on and the hernia was removed.

Another hazard for those living in the Ecuadorian climate was Malaria. Mosquitoes were a permanent threat in Guayaquil, both outside and in, for with no air-conditioning, windows had always to be kept open to capture the faintest breeze.

Pancho caught malaria when he was eight or nine, and suffered from it intermittently until he was twenty. Malaria brings debilitating fever and weakness in the patient, and Pancho was often in bed with this recurring illness. Once he had to go to the hospital for a "quinine cure," where he lay ravaged by "the shakes," his mother sitting by anxiously.

But the most serious affliction endured by the young Ecuadorian was rickets. Rickets is a childhood disorder caused by malnutrition, in particular the lack of vitamin C, calcium, and phosphate.

Mercifully rare in developed countries, rickets causes skeletal deformities, most commonly bowlegs. Pancho had rickets because as a young child he did not have an adequate diet, and his body never forgave him.

Pancho's father, Domingo Cano, provided as best he could for his growing family. A handsome, strong man, six-feet-two-inches tall, he worked as guardian to the property of one of the wealthiest men in Guayaquil, Don Juan Jose Medina.

Medina, who had been educated in England and was an important banker in town, became godfather to Pancho. Medina was very concerned about the boy's development and thought Pancho should take up an activity that would strengthen his bones, fill out his muscles, and add much-needed bulk to the child's stunted frame.

The Godfather

Medina decided that that activity should be his own favorite sport, tennis. Senor Medina was on the board of the Guayaquil Tennis Club, a small, elite club that consisted of only five hundred members. In Ecuador, indeed all over the world, tennis was considered an upper-class sport, a rich man’s game, available only to those who could afford to spend their leisure time using expensively made rackets to hit expensively produced balls at each other across expensively woven nets on expensively cared-for surfaces in expensively maintained clubs while wearing expensive, long white trousers with expensive white sweaters and expensive shoes.

Medina decided to hire Domingo Cano to be caretaker of the Guayaquil Tennis Club. This position gave Cano not only a regular salary but also lodging. The family was given a small house on the tennis club grounds. In return, Cano was to look after the courts, maintain the grounds and the clubhouse, and provide services for the members including ball boys.

Panchito would become, in effect, assistant to his father, and at the same time start to play tennis. It was an entirely private arrangement, of course. The club members did not see or think much about their staff.

As long as the club and the courts were kept in tip-top shape, and there were ball boys to pick up the balls, who actually did these jobs was not of much concern. Pancho, like three or four other little boys hired by the club, scurried about collecting balls and throwing them when required to the players, otherwise making themselves as invisible as possible. Pancho was the youngest of these ball boys.

"My dad had me picking up balls, brushing the lines, fixing the net, handing towels to members," Pancho recalled.

The club had four courts, all cement, which were mostly busy on weekends when the members were not at work, but Pancho would come every day after school to help his father.

In elementary school in Guayaquil, Pancho was a good student, particularly in mathematics. "I was good at numbers," he said. He had good teachers. But he was lonely.

Isolation

Because he was so frail and undersized, his schoolmates teased him unmercifully and called him mancan, fairy. Every day after school, instead of playing sports or simply hanging out with friends, he went to the tennis club, a place off limits to his classmates. It was an isolated life for a child.

One day, inevitably, he picked up a tennis racket. It was old, abandoned, thrown out by one of the members. It was far too big for him. He had to lift it with both hands. But Pancho put his hands round the handle, bounced a ball, and swung.

In the beginning, I wasn’t interested," he remembered. “My friends at school played soccer. But when I hit the ball against a wall, I liked it."

Tennis, this mysterious game that his school friends knew nothing about, was something Pancho could learn privately, with his father, at the club. When the courts were empty, his father would pick up a racket and take his son to hit with him. "We'd sneak on to the courts," Pancho recalled.

His mother, however, was the real athlete in the family. Pancho's sister, Elvira, became a national champion basketball player. His mother would also play tennis with Panchito, and for a while, she beat him. "He hated it so much, finally she let him beat her," Elvira remembered.

But tennis was not what Francisca wanted for her son, nor was basketball what she wanted for her daughter. She expected her five girls to stay home, to help in the house, and prepare for good marriages. Pancho's mother felt uneasy about his growing passion for tennis.

It kept him away from the house, away from her. Both his brothers grew to be over 6 feet tall. But her firstborn was precious to her because of his frailty. She nurtured him, cared for him, and prayed for him. Being the most vulnerable, he was perhaps her favorite.

Very religious, Senora Cano wanted him to be religious also. She insisted that every time they passed a church he go in and take the holy water.

She was also the disciplinarian in the family. "She used to give us the belt," Elvira said. "I remember Pancho objecting, saying 'Mama, you're going to hit a tennis champion?'"

Pancho’s mother would go to the courts with her son, but she often found it distressing. He did not have proper tennis shoes. They were made from rubber tires. His socks were not long and white, like those of the other players. She could not afford those luxuries.

Endemic Prejudice

Worse she saw how her boy was treated by the club members when he was working as a ball boy, telling this story near the end of her life.

"I remember one time when he sat on the chair of one of the members. “What the hell are you doing sitting there?" the member asked. “You have to sit over there, on the stairs." And so her son left quietly to sit on the stairs. He was also forbidden to use the member’s bathroom.

But already showing the sense of humor and the confidence he was later famous for, he would tell his mother: “They tell me not to use their chairs or their bathroom, but when they are not there I sit on their chairs and I shower as many times as I want, and someday I will be sitting in those seats right in front of all of them."

So his mother grew to accept her son’s ambition and passion for the game. As he grew older, she was drawn into his obsession and began to encourage him. She would come to the club at twilight, after all the members had gone home, and take Pancho on to the empty courts, hitting back and forth with her tireless son.

Once he became a teenager, there was no question of who was beating whom. They would play until it was too dark to see the ball. How he resented that coming of darkness. "I remember he would cry because he couldn’t play in the daytime," his sister Elvira said, "Only at night."

Pancho was the eldest child and favorite of his mother. But he was also the most responsible. As is often the case with the eldest son, he was acutely aware of his position in the family.

As a child, he would take a burro into the hillsides outside the city and bring back firewood. There was nothing he would not do to help his parents, brothers, and sisters. He left school to work for his family. It was a painful decision. He was twelve years old.

He admitted later that his childhood was sad, because his life at the club, and leaving school early, separated him from his friends.

"They weren't allowed there. It was a private club, and we were just servants. I couldn't get them in." The lack of money also isolated him. "I never had a bike. I couldn't go anywhere, not even to the beach."

"In those days," he said, laughing at the recollection, "if we saw a plane we thought it was a bird!" He would look longingly at the magnificent Grace Line ships that sailed in and out of the port of Guayaquil.

Boat to Somewhere

"Someday I will go on a boat like that away from here," he would promise himself. "One day I will become somebody." Meanwhile, there was no alternative for him except to go on hitting balls against the wall at the Guayaquil Tennis Club.

He began to commit himself more and more to learning about the game. Although he saw that all the grown-up players at the club used one-handed forehands and backhands, he found he could hit more powerfully by continuing to use both hands on his forehand.

He watched the better players, analyzing their technique, and then copied it later by himself, playing against the wall. He learned from the movements of the highly regarded, left-handed player Don Nelson Vraga, who had a tenacious fighting spirit that Pancho admired. He worked on abandoned old rackets as though they were priceless, binding the disintegrating strings with tape to make them last longer.

He began to improve. "By playing against the wall all the time I knew the ball came back fast, and I learned to hit the ball early." Born with instincts and coordination in spite of his physical disadvantages, Pancho began to develop incredible timing.

He also started working out on a rowing machine, a new addition to the club. His godfather, J. J. Medina, saw to it that his godchild was smuggled into the hallowed exercise room when nobody else was around. By about the age of eleven, the relentless practice, the intense concentration, and the focused mind started to pay dividends.

Top Flight

He acquired a proper racket, a well-worn Spaulding Top Flight, abandoned at the club by a visiting Brazilian. "He looked at it with pride," recalled his mother, "as if it were a treasure, and he used it for many years."

People began to take notice. "Soon," Pancho said with a glint in his eye, "I began beating the big boys." Working at the club, he would sometimes be invited by members to hit with them.

His consistency made him almost like a ball machine. “I was a ball hitter for them and they would pay me thirty cents, fifty cents, to play with them."

Fifty cents for Pancho and his family was a small fortune. His parents' struggle to provide for such a large brood remained a constant anxiety, particularly for his mother, who often could not pay the bills.

His father's attitude toward money was more pragmatic. "Don't go out in the rain, we have no raincoats," was the kind of advice he offered his children. Or, "If you must buy a suit, buy a black one that you can wear to wakes and get free food."

For their son to bring home money was a lifesaver. To discover that tennis was a way to provide funds for the family was a revelation.

"Playing tennis brought money to the house, and so my parents encouraged it," Pancho said.

But some members would not pay what they promised. "I would wait outside while they changed and then ask for my thirty cents!" This was Pancho’s first exposure to the thoughtlessness of the wealthy.

Soon the club members were all aware of this determined youngster always hanging around the courts. By playing with the big boys, Pancho developed his game and learned from them, revealing an intense competitiveness that surprised his opponents.

In 1935, when Pancho was thirteen, an important visitor came to the club. He was Francisco Rodriguez Garzon, a well-known journalist and editor of the sports section of the local daily newspaper. He saw Pancho play, and a few days later, the newspaper published a story about him that caused a minor sensation.

As soon as I saw him," Rodriguez wrote, “he entered deep in my soul. He was afraid that the members would get upset and he did not want to say much of his passion for tennis, of his abilities, and of what he could do. But upon talking to the members of the tennis club I began thinking about what a young man with his talents, could achieve."

National Hero of the Future

Thus began a lifelong love affair between that local newspaper and the new young star. The article announced to the world for the first time that Guayaquil had someone who might one day become a national hero.

The members of the Guayaquil Tennis Club could no longer ignore him. Pancho began to beat their best players on a regular basis. "They did not always like it," he grinned.

On one occasion a well-known North American player came to play at the club. He had heard about the ball boy with the remarkable flair for tennis and was intrigued enough to ask the club if he might play the kid. The club officials reluctantly agreed. Pancho won the match with ease.

The visiting Gringo was very impressed, told the club they had a seriously gifted player on their hands, and urged them to stop employing him as a ball boy and allow him the opportunity to make a career out of tennis.

"This boy, when he is seventeen, will shine, and will make his country shine."

Some of the club members still found it difficult to accept that the little Indian might be a serious contender as a tennis player.

But one family began to take an interest in this exceptional talent in their midst. In 1937, Luis Eduardo Bruckmann Burton and his wife, Angela, decided to take personal charge of the club's prodigy.

They invited Pancho to spend time with them in their summer house in Quito. They did not know then that he would become a great player, but they had heard the stories and understood that they could help him by taking care of him for a while.

Quito, the capital of Ecuador, is a beautiful city situated high up in the mountains, where the air is much better and clearer than in Guayaquil, and where those who can afford it prefer to spend the less attractive months of the year.

The Bruckmann Burtons offered Pancho a generous deal. They would feed him nourishing food, see that he had proper sleep, and allow him to breathe good air in a healthy environment.

In return, he would teach tennis to their two teenage daughters, IIse and Olga. It was a splendid opportunity, and Pancho seized it with gratitude.

The Bruckmann Burtons kept their promise. In Quito, he became stronger, adding muscle. Pancho returned in far better shape than when he had left. He was now sixteen years old, and his first big test as a tennis player was about to take place.