The Shadow

Caroline Seebohm

While Francisco Segura was striding through tournaments as the highest ranked pro player, a shadow began to haunt his progress. At the end of I953, perhaps the greatest of Segura's three great years on the tour, that shadow turned into a reality.

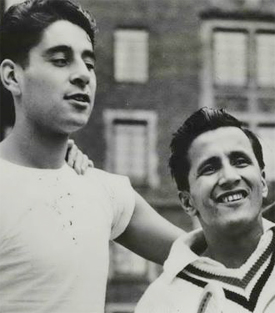

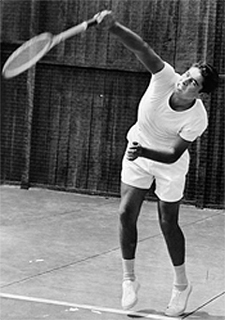

Richard Gonzales had paid his dues was about to claim the crown from his compatriot. In I954, Gonzales seized the limelight and never let it go. For a long time now Gonzales had also been known as Pancho. Like Segura, he was a Latino, dark-skinned, from a family born across the border. Didn’t all gringos call people like that Pancho? He was "Big Pancho" and Segura became "Little Pancho."

But while Segura did not mind the name, Richard Gonzales minded a lot. He thought it insulting. It epitomized the attitude whites had toward him and all Latinos. Beneath the condescending name, he saw hostility and mistrust. He was not wrong. The first year of Gonzales's pro tour, he was traveling in a car with his brother, Manuel, plus Segura and Dinny Pails from a tournament in Dallas.

He had just learned that his son Michael had been born. A celebration was in order. They picked up some beer and started the long trip to Shreveport, Louisiana, where they were to play next. A few miles outside Dallas, Big Pancho wanted to stop at a small roadside diner. The four men went inside to eat. The waitress ignored them. Unaware of the three white men sitting at the counter, Gonzales called out to her for service.

"We don’t serve your kind here," drawled a deep Texas voice. Gonzales turned and stared. His brother grabbed his arm and urged him to stay calm. While Segura and Pails quickly scrambled to get out of the diner, Gonzales moved slowly, in his loping walk, toward the exit. One of the Texans stood in his way, and as he continued to move to the door, another one called out, "You colored wetback spics, go home to your greasy mamas." They laughed and went on jeering, "You spineless yellow-skinned wetbacks!"

Gonzales turned on them and within seconds they were fighting viciously. Gonzales was out numbered, was hit hard, and knocked to the ground. He staggered out into the road toward the car. "Get my gun," he yelled to Manuel, "it's in the car!"

Suddenly an old black man appeared and told them to get out. "They've hung people for what you've done," he warned them. Still furious, Gonzales got into the car and they drove away. "In those days, Mexicans weren’t too welcome in Texas," Segura said later in a wry understatement. "We had to keep him from fighting. He had no fear. He'd challenge anybody."

That incident was only one in a year that humiliated Gonzales from start to finish. At a too young age, he had turned professional in a fanfare of publicity, only to find he could not work with--or defeat--Jack Kramer.

Hate

What was submerged under all these defeats was something more insidious. Without anyone saying it, it was clear that Kramer's favorites were the big, white, attractive all-American players who had been playing with him over the years, such as Ted Schroeder, Frankie Parker, Frank Kovacs, and later Tony Trabert. They were the stars in Kramer's hierarchy and were treated accordingly, as were the glamorous Australians who joined the tour in the early fifties. Kramer argued that his strategy was simply about squeezing money out of the increasingly unsuccessful tour.

After losing the head to head tour badly against Kramer, Gonzales was dropped at the end of 1950. To add to the insult of women being brought in to replace him on the court, he went home to Los Angeles to find his wife, Henrietta, now the mother of two boys, living in squalor, with the house full of soiled diapers and dirty dishes.

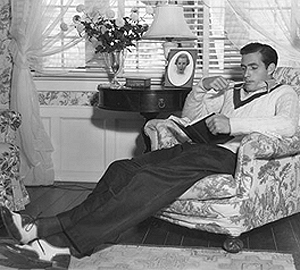

Soon Big Pancho found himself trying to be a family man instead of a world-famous athlete, and he hated it. He was twenty-two years old. He played with his dogs, gambled, tinkered with cars, became involved in drag racing. What had happened to his tennis? The newspapers were already saying that he was washed up. "The beating he had taken from Kramer had undoubtedly broken his spirit," columnist Arthur Marx wrote.

From 1952 to 1953, while Little Pancho was wowing audiences all over the world with his amusing shenanigans and brilliant tennis, Big Pancho played a few limited events. In 1952 he beat the legendary Bill Tilden 6-1, 6-2 in an American tour event, and later, at Wembley, he defeated Kramer in a dazzling display, after being two sets down, 3-6, 3-6, 6-2, 6-4: 7-5.

But 1953 was another hard year, with Sedgman beating him in the French Pro Champs. Choosing not to travel to Europe that summer, he came back strongly at the California Pro Champs in Beverly Hills, where he won the title against Don Budge and at the Canadian Pro Champs, easily defeating Bobby Riggs in the final. These victories paved the way for his real comeback in 1954. But to reach the top, he had to unseat the current champion, his traveling companion and amigo, Pancho Segura.

Outsiders

In those days, they were both outsiders, dark-skinned strangers on the court, noticeable for their ethnicity, in contrast to Kramer’s favored white stars. Little Pancho had learned to live with it, even enjoy it, playing to the minority fans, teasing the big boys, making the most of his Latin background. But Big Pancho was different. His violent childhood, rebelliousness, and sensitivity to slights made him vulnerable.

"Prior to the tour," Gonzales explained, "Kramer had set the tone for our relationship by his obvious dislike toward me. During the tour that dislike grew to hatred and I grew to hate him as much as he hated me.

"The hatred and anger inside of me emerged as a driving force that would eventually make me a dominating figure in professional tennis." As the tour continued, Segura watched his friend get better and better at the game of tennis. He also watched him off the court, getting angrier and angrier at his treatment from the authorities. Unrepentant, Big Pancho found it hard to deal with the elitist culture of tennis.

He was used to street life, gambling, smoking, drinking, living on the edge. People called him "pachuco," a street kid. He resented the name, but it was not far from the truth. Now he was supposed to train, to care for his body, to avoid trouble, to talk politely, to wear suits, and show up at publicity events. He was never able to fully accept it.

When Gonzales was invited to visit Europe after winning his big amateur titles in 1949, he was approached by an acquaintance called Neil McCarthy, who saw that the young Mexican-American needed help. McCarthy was an elderly attorney with a passion for tennis, and after he learned that Gonzales was going to France, Germany, and England, he decided he would try to help. He took Gonzales shopping and bought him suits and shirts and evening clothes for the trip.

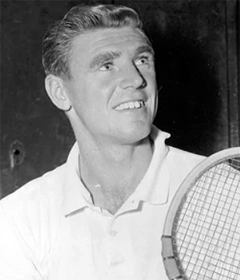

Another such patron for Gonzales was Frank Shields (grandfather of actress Brooke Shields), who was a fine Davis Cup player, and well-connected socially. Shields also took Gonzales under his wing when the Mexican-American was at the beginning of his career and tried to make him eat better, dress better, and gamble less in order to prepare himself for the arduous life of a professional tennis player.

There were many similarities between Segura and Gonzales. They both had strong, ambitious mothers who worshiped their eldest sons and wanted to see them succeed. They both came from large families, with never enough money. They were both ferociously competitive and determined to improve their games to try to win titles.

They were both very intelligent, although Gonzales never exercised his mind the way Segura did. "He was never curious about anything," Segura recalled. "He never wanted to know anything. I used to say to him, "You should buy Time magazine and see what's going on in the world. And he'd say, 'What the hell do I need that for? I have you!'"

Little Pancho laughed uproariously at Richard's carefree responses, although he knew there was a destructive side. Particularly in his financial dealings with Jack Kramer, Gonzales was like a mad bull, charging again and again into Kramer's stonewalling tactics.

Segura knew he couldn't help Gonzales in these battles, which became increasingly bitter, and damaged both men's careers. Gonzales called Kramer "Czar" Kramer, and fought to the end about his right to bigger percentages and better contracts. Kramer forced him to play places and make appearances that Gonzales felt were not contractually binding, and finally in 1960 he brought a lawsuit against the Czar. He won the arbitration, and with that Gonzales turned his back on Kramer for good.

"He was a nice guy if he liked you," Segura said. "If he didn't like you, it didn't matter if you had money or power, he didn't give a damn."

As the two got to know each other better, Segura and Gonzales paired up against the gringos. One of Kramer's tour routines involved a seeding system, reevaluated every ten matches. If there were four players going out to play, the first seed played the fourth seed and the second seed played the third. The two winners then played each other the second night.

The man seeded fourth had the hardest draw, playing the first seed on the first night. The players called this position "the cellar," and they worked mightily to avoid being there. Gonzales and Segura found ways to stay out of the cellar.

"Segura was a master at working angles. I enjoyed his manipulative escapades," Gonzales recalled. He gave the example of how Segura planned to help Gonzales to beat Sedgrnan.

One night Big and Little Pancho were watching an Ice Follies performance in Philadelphia together, and they started talking about the Sedgman problem. "We gotta keep him in the cellar," Segura said. Big Pancho asked what Segura had in mind. What Segura had in mind was simple. Take Sedgman to the party being held later that night, make sure he had a few drinks, and leave him there.

The plan worked like a charm. Sedgman stayed all night at the party and didn't recover for a week, meanwhile losing all his matches and staying permanently in the cellar. Gonzales appreciated that kind of strategy from his tennis amigo.

People who doubted the competitiveness of the tour greatly underestimated the players' desire to win. Little Pancho recalled one occasion when Bobby Riggs was sick and asked Jack to "carry" him, meaning, "Don’t beat me too badly." Segura shook his head at the memory and laughed.

"Jack beat the crap out of him. Jack was tough. If you beat him, he wouldn’t talk to you for two or three days."

Despite his competitive desire, Gonzales often let his weight balloon up, would stay out late, or would not show up. And yet he famously hated to lose. Several players remembered occasions when they beat Gonzales and he would not speak to them for weeks.

Better and More Volatile

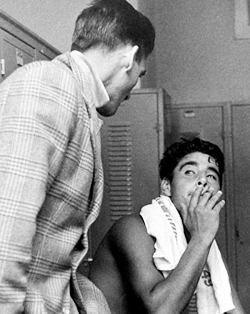

The better Gonzales became at tennis, the more unreliable he became. He knew he was a star, and behaved like one. He would explode on the court, like John McEnroe twenty years later.

He frequently threw his racket on the ground. He would shout at linesmen, "You need a Seeing Eye dog!" Or, "When was the last time you saw an eye doctor?"

People began to expect fireworks from him, and they usually got it. "He got mad but he was funny, he made them laugh," Segura said. "He created excitement, you know, because in those days tennis was very quiet. You couldn’t talk."

Like Segura, with his self-encouragement, "Ahora, Pancho, Ahora, Vamos!" Gonzales made a lot of noise on the court.

If he created excitement, he also aroused anger among his fellow players. One time the group was in Paris, about to fly to Copenhagen, where they were to play on the weekend . "Gonzales suddenly decided to go from Paris to Los Angeles on Sunday night," Segura remembered, "Then fly on Thursday to Copenhagen," said Segura.

"The promoter in Copenhagen is dying because Gonzales is the marquee name, and we are all dying because we need him there for the publicity and practice." In the end he showed up, but this was not the first or the last time he played games with his tour mates, and they did not like it.

Little Pancho, was not personally immune to Gonzales's erratic behavior. After they had both left the tour, they were due to play doubles together in an over forty five tournament at Wimbledon. But Big Pancho got upset about something and took off to California. "He dropped me. I had to default."

They used to go out together in the evenings, but Gonzales was difficult to please, often ignoring the women who consistently threw themselves at him. Little Pancho laughed and confessed he got sick of going out with him, since Gonzales was always the target of all the females.

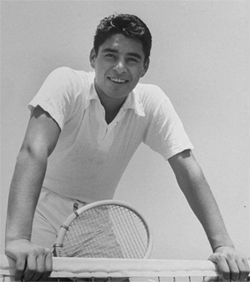

The dark-eyed, dark-skinned, six-foot-three tennis god, with the mysterious scar and the panther-like body, was a magnet to the opposite sex.

"He could have been a movie star," Segura said. "I remember Jack Warner sending an agent to get him to sign a contract. They were going to train him, teach him how to walk, how to handle a knife and fork. But he said no. He didn’t like it."

"Women were his downfall," Segura said. He had seen Gonzales fall for the wrong women at the wrong time. He knew about his troubles with his first wife, Henrietta, his divorce and marriage to Madelyn Darrow.

Darrow aspired to higher social standing and tried changing the spelling of Gonzales back to Gonzalez with a "z" because that's how it was spelled in Castilian Spanish. They divorced and then briefly remarried.

Segura sighed over his friend's passion for a dental assistant whom he impulsively married and then abandoned with their baby in a hotel room in London while he played at Wimbledon.

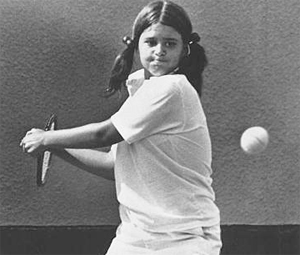

Big Pancho’s last marriage was to Rita Agassi, the sister of Andre Agassi. Gonzales had coached Rita when she was a thirteen-year-old at Caesar's Palace in Las Vegas. After living together for three years, they married in 1998. He was fifty-five, and she was twenty-three. They had a son, Skylar, and divorced after ten years. In all, Richard Gonzales had six marriages and eight children. Segura once joked that the nicest thing Gonzales ever said to his wives was, "Shut up."

"He was a loner," Segura said. "He would go out at night alone. He liked tinkering with cars and would drive off into the mountains for hours. Or go hunting by himself." If the lone wolf had a friend in this cutthroat world, it was Pancho Segura.

"Segura is like a very close older brother to me," Gonzales once told author Joel Drucker.

"He has such energy and love for life that I would listen to him talk about anything--tennis, events, politics, poverty. He seemed aware of the world at a young age."

As the 1950s progressed, Gonzales began to beat Segura on a regular basis. In Mexico and later in the U.S. pro Hard Court Championships, Gonzales twice beat Segura.

No longer was Segura the top-ranked pro in the world, or even in the United States. Richard Gonzales claimed those titles for himself, and he earned them. In 1954 for the first time Gonzales won the pro number one ranking.

In October Gonzales beat Kramer twice, in Manila and in Hong Kong, and at the end of 1954, he won the Australian pro series over Sedgman and Segura. From then on, Gonzales totally dominated the game until 1962.

But Segura loved playing Gonzales and continued to have a few wins. In conversations with Joel Drucker, Gonzales and Segura relived a memorable match in Sydney, Australia, in 1957, that Drucker later described.

Down two sets to love in his quarterfinal versus Australian Rex Hartwig, Segura heeded Gonzales's advice to put on spikes to gain better footing. Playing brilliantly, Segura fought back to win, but his wrist was throbbing. Gonzales helped out, massaging his friend's wrist, getting him treatment from a trainer in advance of Segura's next match-a semi-final against Gonzales.

The next day, on the fast grass court that had bedeviled Segura back in 1940, Gonzales sprinted off to a big lead, taking the first two sets. But Segura dug in, winning the last three sets.

"Boy, I was ticked," said Gonzales, laughing. "I'd helped him recuperate and then he beat me."

The next day Segura whipped Australian Frank Sedgman in three straight sets. But it's the win over Gonzales that he cherished the most. "Gonzales is the player that I wanted to play all my life," said Segura. "It's that simple."