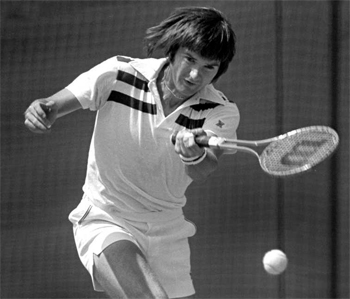

Gonzalez and Laver

Doreen Gonzales

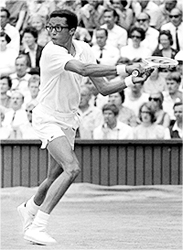

After his amazing 2-day, five set win over Charlie Pasarell, the 41 year old Richard Gonzalez advanced in the tournament until he lost to Arthur Ashe in the fourth round of action. Rod Laver won the tournament.

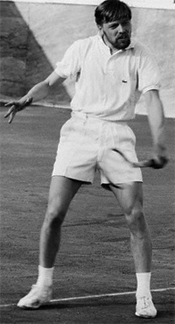

Laver's win was as remarkable as Gonzalez's victory over Pasarell. It was Laver's second win in a row at Wimbledon, and Laver was on his way to becoming the first player ever to win the Grand Slam twice.

His first Grand Slam had been in 1962. By winning Wimbledon in 1969, he had three of the four victories necessary to do it again.

But Laver's amazing accomplishment at Wimbledon in 1969 was overshadowed in many news reports by Gonzalez's victory over Pasarell. Laver was not surprised.

He commented, "That's Pancho for you, always stealing the show." Even today when play at Wimbledon is stopped due to rain, audiences are often entertained by a broadcast of the Gonzalez-Pasarell match.

Laver completed his second Grand Slam by beating Tony Roche in the 1969 U.S. final at Forest Hills. No other player has ever won two Grand Slams. As a result, many consider Laver to be the greatest player that ever lived.

Slam Titles?

Yet many experts believe it was the rules rather than skill that kept Gonzalez from accomplishing Laver's feat. As a professional, he could not compete in Grand Slam tournaments for almost twenty years. The amazing reality--hard to fathom in our day--is that Gonzalez only played Wimbledon twice in over 20 years.

Many people feel that if open tennis had come earlier, Gonzalez would certainly hold the record for the most Grand Slam titles won. As proof of their claim, they note that when he did face Laver in competition, Gonzalez was well past his prime.

Nonetheless, he often beat Laver, even when Richard was in his forties. Try to imagine a player over 40 today capable of competing with, much less defeating the top player in the world, and one of the game's all time greats.

After Wimbledon, Gonzalez went into training for the 1969 U.S. Open. He smoked less, watched his weight, and played tennis all day long.

He also rested. This was a much more conscientious approach to conditioning than Gonzalez had practiced in his younger years. But Gonzalez knew that his age demanded better physical preparation.

One writer wrote that the most important part of Gonzalez's training program was getting himself in the mood to fight. Gonzalez retreated, the writer said, "to dwell on his resentments and work himself into a mean, sullen mood, because that's the way he plays best."

Gonzalez responded by saying, "I've always fought, because I've always been pushed around."

Although age was affecting Gonzalez's physical prowess, it was not dulling his determination. In fact, it seemed that Gonzalez fought harder now than ever before and that winning had become an obsession.

Competition and Charisma

But Gonzalez explained his attitude differently. He said that open tennis had brought new competition to tennis, and he wanted to be a part of it.

Age had not detracted from Gonzalez's charisma either. His jet black hair was graying, but he was still slim and fit. His court presence remained overpowering.

As one writer observed, "Women find him fascinating when he steps on the court, gaunt and sinister, and begins stalking his prey. Men are intrigued by his hoodlum appeal, his angry and sullen manner." Not to mention his tennis.

The organizers of the 1969 U.S. Open were fully aware of Gonzalez's crowd appeal. They expected Gonzalez to draw large numbers of spectators, so they scheduled his matches in the stadium where there was the most seating. In the meantime, higher-ranked players competed on the outside courts.

Gonzalez easily beat his opponents during the first two rounds of play. In the third round he was trailing Torben Ulrich two sets to one, when the players took a break, customary in those days between the third and fourth sets.

Gonzalez's feet hurt and his legs ached. For a few moments, he thought about retiring, saying he felt a hundred years old. Then he walked back on the court and won the match.

But Gonzalez lost in the next round. He was forty-one years old, and his age could not be denied in the physically grueling world of championship tennis. His back became stiff and his nervous energy gave him stomach aches. In addition, his eyes seemed to be getting worse.

Gonzalez wore glasses for reading and watching television, but he would not wear them for tennis. When he did, he said he had difficulty telling exactly where the ball was.

Instead he took mineral tablets that he felt helped his vision. When a reporter asked him why he kept playing, Gonzalez replied, "Because I'm not smart, that is why. I like to punish myself."

Overcoming Age

But Gonzalez was not about to quit playing because of aches and pains. Instead he found ways to overcome them. He practiced daily to keep his body in condition. He used an aluminum racket because it was lighter than wood. This enabled him to gain fractions of a second in speed.

He cut the pockets out of his tennis shorts to get rid of the extra weight they created when they were wet with sweat. Gonzalez also stayed calmer on the court, knowing that anger burns up energy.

Gonzalez's most powerful weapon, though, was his mind. Hoping to wear down an opponent, he looked for each one's weakness and played to it.

He had always outsmarted opponents before. Now he honed strategy to an art form. Many players described Gonzalez as having the best tactical expertise of anyone in the game. As for Gonzalez, he said he would rather have the energy of a youngster than all the knowledge in the world.

Yet he won the 1969 Pacific Southwest Tournament. Next came the Howard Hughes Open in Las Vegas, where Gonzalez conquered the world's sixth ranked John Newcombe and third ranked Rosewall to work his way to the final.

Opposing Gonzalez for the title was the second ranked Arthur Ashe. Gonzalez seemed to be on fire during this match. He made one perfectly placed shot after another.

Ashe even applauded Gonzalez after one outstanding stroke. Gonzalez defeated Ashe 6-0, 6-2, 6-4 to win the tournament. Again this was an almost incomprehensible achievement. At 41, Richard had beaten three hall of fame players in succession, all of whom where 10 to 20 years younger.

(To see an amazing documentary on this event, and Richard's life, Click Here.)

At 41 his ranking was moving up! Gonzalez had begun that year ranked tenth in the world tennis standings. He finished it ranked number six.

Retirement?

Then Gonzalez announced another retirement. During the past decade he and Madelyn had been divorced. Now the two were remarried.

Gonzalez wanted to spend more time with her and their children. He also wanted to devote his energy to developing a tennis camp at his home in Malibu.

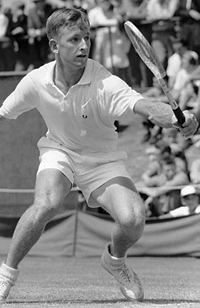

Even so, Gonzalez entered a series of "winner-take-all" matches in 1970. In the first contest he faced the now two-time Grand Slam winner, Rod Laver. More than 15,000 fans came to Madison Square Garden in New York City to watch.

Gonzalez knew strategy would play a major role in this match. Laver was only five feet seven inches--not very tall as tennis players went. Gonzalez decided to use this to his advantage.

As often as he could, when Laver advanced to the net, Gonzalez lobbed the ball over Laver's head and out of his reach. During the final two sets, his game plan began to payoff.

After hitting lob after lob that dropped just inches beyond Laver's reach, Gonzalez surprised him with powerful low drives across the net. Using this strategy, the old warrior was able to beat Laver in five hard-fought sets and earn the $10,000 winner's purse.

A week later Gonzalez won another $10,000 by beating John Newcombe who would win Wimbledon later that year. These are some of the facts that lead experts to believe Gonzalez's Grand Slam potential could have been almost unlimited.

In 1971, Gonzalez entered the Pacific Southwest Tournament where he worked his way to the final. There he met up-and-coming young Jimmy Connors. But youth held no advantage, and Gonzalez beat the seventeen-year-old to win the tournament.

Gonzalez was forty-three years old and supposedly in the twilight of his career. Yet he had beaten another future all time great less than half his age.

One writer observed of Gonzalez "somehow the sun never quite sets." But not even Richard Gonzalez could keep the sun from setting for ever.