Pancho Gonzalez:

Outsider Champion

Doreen Gonzales

After winning the U. S. Nationals in 1949, suddenly, Richard Gonzalez was the most popular tennis player in the nation. (Click Here for how that happened.) Articles about him appeared in The New York Times newspaper and in Time and Life magazines.

Each article emphasized that no one had ever risen to the top so quickly. As Times tennis writer Allison Danzig put it, "The rankest outsider of modern times sits on the tennis throne today."

Gonzalez was unique in other ways, too. He had a distinctive playing style that many writers compared to the movements of a jungle cat. He crouched low in preparation for his opponent's shots. When one came, he pounced on the ball with great fury.

But it was Gonzalez's serve that received the most attention. Enthusiasts described it as a rocket.

Gonzalez's style created excitement among spectators. For years, tennis fans had been watching the same players compete in matches that often seemed routine. But no one could tell what would happen in a Gonzalez match. Wondering if he would make an inexplicable error or hit a brilliant shot, people leaned forward in their seats to watch him play.

|

Unpredictable, charming, handsome. |

After he won the National Championships in 1948, Gonzalez rose to fame. Many tennis fans were charmed by his intensity on the court and by his good looks.

Gonzalez himself called his game unpredictable. "Sometimes my forehand is my weakness," he explained, and, "sometimes my backhand. It all depends on how I'm feeling that day."

Fans also found the new champion's background intriguing. Some writers characterized him as rebellious and emphasized his truancy during high school. This soon earned him the title of the bad boy of tennis.

In a world that presented its champions as well-mannered young men, Gonzalez became characterized as a rebel from a poor Mexican-American family. Some writers called him "the kid from the other side of the tracks."

Gonzalez felt that this description was an exaggeration of the working-class home in which he grew up. But the image stuck and many people found it fascinating.

In addition, Gonzalez had a tremendous charisma that drew people to him. He was confident and easygoing on the court. He was handsome. Writers noted that groups of young ladies often came to watch Gonzalez play.

Fans also found Gonzalez's heritage intriguing. He was the first person of color to win the national title. Some reporters emphasized his Mexican background by calling him Pancho, Chuck Pate's nickname for his friend. But the name felt different coming from the press, and Gonzalez hated it.

|

Avid fans and many of them women. |

Pancho was a name some people used to address Mexican American males without bothering to learn their names. It was sometimes intended to refer to a person of low social status. Many Mexican-Americans, in fact, considered the nickname to be a racial slur. It reminded them of the negative stereotype some people had about them. This stereotype unfairly portrayed Mexicans as stupid and lazy.

Indeed, writers continued reporting that Gonzalez had a lackadaisical approach to life and tennis. One wrote, "Next to eating Mexican food, the thing California-born Richard A. Gonzalez probably enjoys more than anything else is taking life easy. When the mood hits him, 'Pancho' plays tennis."

While the press called Gonzalez "Pancho," the people closest to him respected his wishes and called him Richard. No matter what people called him, though, people did call him.

He was suddenly in demand for radio, newspaper, and magazine interviews. His social calendar filled with parties and dinners in his honor. He was a frequent guest of wealthy tennis fans.

|

Richard, a champion most comfortable in company of old friends. |

Gonzalez was completely at home on the tennis court. But the off court world of championship tennis was not as comfortable. This was a world of the rich and the privileged. Most tennis stars were at ease in this environment. Gonzalez was not.

His working-class background had given him no exposure to this world. He was keenly aware of this and felt out of place at many tennis functions. He much preferred the company of his old friends at Exposition Park.

In fact, Gonzalez still frequented Exposition Park and played tennis with his friends there. Some people commented that this habit would ruin Gonzalez's game.

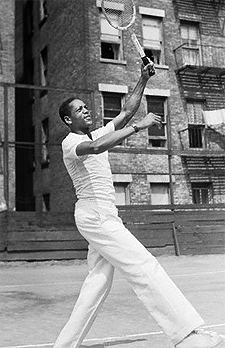

He felt differently. Exposition Park was a unique environment at the time. Many talented players, including those of color, congregated there.

Two of the most well known were Jimmy McDaniels and Oscar Johnson. In 1940, McDaniels had been the Negro National Champion. As for Johnson, he had recently won the National Public Parks Championship in the eighteen-and-under division.

Consequently, competition and expertise at Exposition Park were plentiful. Gonzalez knew his game would not suffer from play there. More bothersome to him were the comments that questioned his status as the top U.S. player.

|

Jimmy McDaniels: a great black player who never reached the mainstream. |

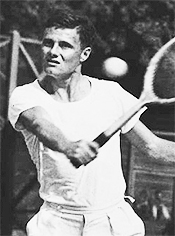

Many people did not see him as a true champion. They believed that if Ted Schroeder had entered the 1948 U.S. National Championships, he would have beaten Gonzalez. Therefore Gonzalez felt he had something to prove when he met Schroeder in the Pacific Southwest Tournament that fall.

Gonzalez stepped up to the task in front of a capacity crowd at the Los Angeles Tennis Club and failed. Schroeder beat him in the tournament's semifinals. In Gonzalez's words, Schroeder "showed no respect at all for the new crown that had been placed on my head."

There would soon be a new joy in Gonzalez's life, though. In December, Henrietta gave birth to a baby boy. They named their new son Richard Alonzo, Jr.

Soon, between fatherhood and socializing, Gonzalez found little time for training. He gained twenty-five pounds. The extra weight hurt his tennis game.

In February, both Gonzalez and Schroeder entered another California tournament. Gonzalez looked forward to another chance to prove he deserved the national title. Then, the day before he was to play Schroeder in the final match, Gonzalez's partner in a doubles match accidentally smashed him in the face with his racket. The blow broke Gonzalez's nose.

Nevertheless, Gonzalez was determined to keep his appointment with Schroeder. The next day he arrived at the court with a bandaged nose. Although he had to breathe out of his mouth, he managed to beat Schroeder 6-2, 6-8, 9-7. Gonzalez later said he would happily break his nose every day of the week if it meant playing that well.

|

Ted Schroeder: no respect for Richard's accomplishments. |

In May, Gonzalez faced Schroeder again in the Southern California Championships. This time Schroeder won in less than forty minutes. One observer noted that the contest was over before Gonzalez had even warmed up. Four days later, Gonzalez played in the French National Championships at Paris where he lost to another American, Budge Patty.

By June, Gonzalez was again feeling the need to prove himself worthy. Wimbledon loomed ahead, the most important amateur tennis tournament of all.

Even so, Gonzalez turned down offers of instruction from the best coaches around, people who might have helped him gain consistency in his shot making. "My game has to be careless," Gonzalez said, defending his decision. "That's the way it's built."

The tension was mounting. Schroeder and other world-class players would be at Wimbledon. Even Gonzalez's mother noticed an uncharacteristic seriousness in her son as the tournament approached.

"Something is happening to Richard," she said. "When he had his picture taken for the passport, I asked the photographer to take four extra pictures. In only one picture was he smiling. He is not so happy any more playing tennis. I do not like that."

One writer put it another way, "Gonzalez knows he must win at Wimbledon, and the knowledge is forcing him, somewhat against his will, to grow up."

|

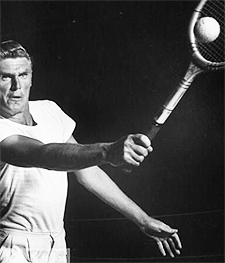

Schroeder with a Wimbledon victory over Drobny. |

In late June 1949, Richard Gonzalez walked onto a Wimbledon court for the first time in his life. In light of his numerous losses that year, the reigning U.S. Champion was seeded second. Schroeder was honored with the number-one spot. This seeding predicted a final match between Gonzalez and Schroeder.

But Gonzalez didn't make it past the third round of play. He was eliminated by Australian Geoff Brown. Schroeder, on the other hand, battled his way to the final where he beat Drobny for the Wimbledon title. Gonzalez did get a measure of revenge when he and Parker beat Schroeder and Mulloy for that year's Wimbledon doubles title.

Some felt that because of his erratic record Gonzalez should not be placed on the 1949 Davis Cup Team. This would have left him deeply disappointed as playing for the U.S. was one of Gonzalez's greatest desires.

When he learned he had made the team, Gonzalez was determined to show he deserved the honor. He defeated two Australians Frank Sedgman and Billy Sidwell to earn two of the three points the U.S. needed to win the competition.

|

Richard defeated the great Australian Sedgman to win the Davis Cup. |

This made an essential member of that year's U.S. Davis Cup team. The wins also boosted Gonzalez's morale, and he felt ready to again win the U.S. National Championship.

Others were not as confident. After reviewing his record, more and more tennis fans seemed to believe that Gonzalez's 1948 victory had been a combination of luck and Schroeder's absence from the tournament. Because of this, one sportswriter called Gonzalez the greatest "cheese champion" in tennis history, meaning that Gonzalez had won the U.S. title in a cheesy or cheap way. Now Gonzalez was dubbed with another nickname he detested-"Gorgo," short for Gorgonzola cheese.

Experts felt that the U.S. Championships final match would be another Gonzalez-Schroeder showdown. Most favored Schroeder. However, these forecasters did not know how much being called the "cheese champion" hurt Gonzalez. Nor did they know how determined this made him.

Something else motivated Gonzalez. A man named Bobby Riggs was looking for new talent. Riggs was the promoter of the most prominent professional tennis tour in the world.

Every year he hired a few of the best players to compete against each other in cities all over the globe. At the time, Riggs was looking for someone to challenge his latest star, Jack Kramer.

|

Bobby Riggs was waiting for Richard. |

Many people assumed that Riggs would ask the winner of the 1949 U.S. National Championships to turn professional. Riggs's touring contract could be worth as much as $75,000. This thought energized Gonzalez.

Being a top-ranked amateur was a career that needed full-time attention. It meant hours of daily training and frequent trips away from home for tournaments. These commitments made it almost impossible for a serious amateur to hold a regular job. Most amateurs, therefore, had to rely on other sources of income to pay their living expenses. Gonzalez had no other sources of income.

"As an amateur," he later reported, "I saved enough from the expense money I received to be able to practice and play occasionally in the off season. I just managed to get by when I was out of competition, but I had to escape."

In addition, Gonzalez now had a family to support. Earning money was a necessity, and doing it by playing professional tennis would be a dream come true. At Forest Hills the tournament officials seeded Schroeder first and Gonzalez second.

Both men won their early rounds of play and advanced to the final. As Gonzalez readied himself for the 1949 championship match, he knew he was playing for more than a title-he was playing for a dream.