The Second Slam

Peter Underwood

In December of 1967 the British LTA endorsed Open Tennis. For the whole 1968 season, at least in Britain--including Wimbledon--it was decided there would be no reference to "amateurs" or "professionals."

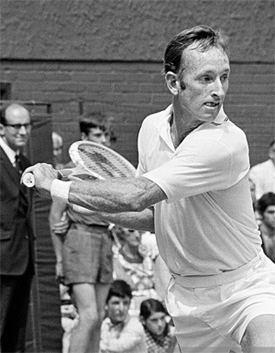

What were the feelings of the unassuming player who was expected to acquire the official--and true--title of World Champion? Rod Laver, the man who fervently believed that drama is best reserved for the tennis court, responded simply: "This will raise the quality of the game and clear it up a bit."

As an amateur, Laver had already won the Grand Slam in 1962, but now he saw a chance for a first in the game's history. He planned to become the first winner of a second Grand Slam, with the difference that now it would be also be a first Open Grand Slam.

Laver knew that this time it would be much harder: the field was tougher and deeper. From beginning to end it was a battle, and one that required his Houdini escape act several times.

Australia

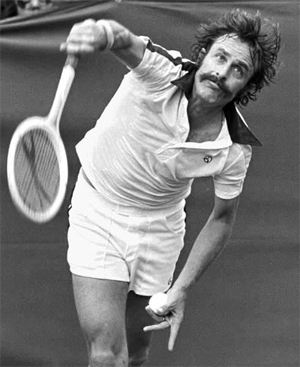

At the beginning, in Australia, the biggest hurdle turned out to be Tony Roche in the semi-final. Roche was another tough butcher's son from the outback and a fellow left-hander who could serve, volley and hit topspin from the ground.

It took four and a half hours on a dreadful grass court in Brisbane's tropical heat, as well as a stroke of luck, for Rod to pull through. For the first time in years--after all he was back in boiling Queensland-- to cool down he'd filled his hat with wet cabbage leaves.

The conditions were so bad and both players so exhausted that Laver admitted it was not The Rocket that got him through, but defense. He won by getting everything back, chipping and slicing, forcing Roche to return yet another slithering ball.

Afterwards he called it the hardest match he ever played. After that marathon test, the final against Andres Gimeno was no trouble at all.

French

Next in line was the French, the only leg of the Slam played on clay, and slow clay at that. Although this looked potentially the roughest of the four legs of the Slam, Laver felt he had at long last worked out how to play on the demanding surface.

Yet in the second round, he was down two sets to love to fellow Australian Dick Creely. He pulled that match out of the fire, but faced more battles in the three final round matches.

In the quarters he faced Gimeno again but this time on Andres' favorite surface. Laver disposed of Gimeno, but appeared to be faltering against an inspired Okker in the semifinal. But after losing the first, Laver lifted his game and won the last three sets 6-0, 6-2, 6-4.

Then it was Ken Rosewall in the final. Rosewall had beaten Laver convincingly in the French final the year before. Nevertheless, in what he said was his finest demonstration of clay court tennis, Rod became champion in straight sets.

Wimbledon

Next Wimbledon. In an early round, he was forced to the fifth set against Stan Smith, a serve-and-volleyer playing the game of his life on fast Wimbledon grass. After that he had to face difficult challenges from Cliff Drysdale and Arthur Ashe.

Drysdale had learned from Gonzales and Rosewall to chip everything he could at Laver's feet. That had produced a win in a warm up tournament.

To counter the strategy, Laver broke the then almost inviolable rule of fast grass--to follow serve to net. When Drysdale woke up, the match was over.

In the Semifinal, Laver faced Ashe. The tall American was a player capable of extraordinary streaks--and he was on one. Jack Kramer said that the first two sets of the match had been the most superlative tennis he had ever seen.

With his opponent hitting out of his mind Laver had at first fallen behind. But, after leveling the match in the second set, he took the third.

At the beginning of the fourth set, the match was still in the balance. Then Laver flashed another piece of magic.

During a rally in the first game, Ashe forced Laver back and way out of court, then went to the net with the whole court open and hit a cross-court drop volley. Laver was about thirty feet from the ball but had anticipated Ashe's shot.

With his backhand, he scooped up the dying ball--and lofted it over Ashe's head into the open court. Against a now demoralized Ashe, Laver went on to win the set 6-0 and therefore the match.

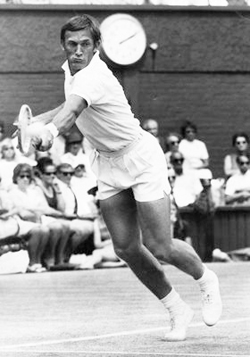

After that, came the triumphant final against Newcombe. Newcombe had one Wimbledon title and he relished the fast true grass.

At 25 years he was approaching the peak of his powerful and intelligent game. Newk had thought hard about his strategy against Laver. He had spent hours sitting in the stands studying the old masters Laver and Rosewall.

Aware that Laver liked pace, Newk decided he wasn't going to offer him any. He chipped returns and when Laver came in he lobbed.

The first set was tough, but Laver held up to take it. Nevertheless, Newk's defensive strategy had started to work: already, many times Laver had been forced to jump for lobs, and the older man was beginning to show it.

Laver began missing a few smashes, and more than a few first serves. The challenger was playing very smart and very well, and his great serve was on. Newcombe took the second set 7 -5 to make it one set all.

In the third set, Newcombe made a crucial service break, and he was up 3-1. He then held serve for 4-1. At this point, to most observers the young gun was playing the game of his life: if he won this set, as he looked almost certain to do, he could take the championship.

Laver explains that it was then that something happened within him. The crowd was getting excited. Here was an old champion in trouble and facing a challenger who was young and brave.

Laver sensed that the spectators were hoping things would get even tougher for him. But he was far from being put out by this. To him, their sentiments were "all right." In the space of a few seconds, the anxiety and fear that he had faced in reaching this point of crisis dissolved. "I was on my stage, one that I knew and loved, and it was up to me to strut like a proud player and do my act."

At 1-4, and 30-all, Laver was serving in a game he had to win. Newcombe threw up one more lob. It was pretty good--but not good enough. Laver buried a glorious smash for 40-30.

Then Laver stepped to the line and cracked an ace. "It felt fantastic." Suddenly he believed he could do anything.

It was now 4-2, with Newcombe still a service break ahead and serving. After Laver won the first point of the game for 0-15, a rally developed on the second point.

Newcombe hit a forehand crosscourt wide to Laver's right. Newcombe edged a bit to his left, figuring all Laver could do was go down the line.

Although everybody knew that Laver's favorite shot was the down the line backhand, struck hard with topspin, he made up his mind to go the other way. He sliced a low, softish crosscourt skimmer.

The ball, invested with a life of its own, was running almost parallel to the net. Then it crossed and dropped within an inch of the sideline. Laver later said he couldn't believe the angle. Neither could Newcombe. He was shocked.

After that one shot, the match was more or less over. From then on, Laver was playing out of his mind. He won the third set easily --and then the fourth for the championships. "You don't plan a shot like that," Laver said. "I had a general direction in mind and the rest just happened."

US Open

For Laver to win the fourth and last leg of the Slam, the US at Forest Hills, he needed to come up with more than great shots. Early in the tournament he struggled in five sets against Dennis Ralston, and then had to survive another battle against his old foe Emerson.

The Final turned out to be once more against Roche, who had an overall 5-3 match advantage over Laver for the year. The Forest Hills grass was always suspect, and conditions had been made worse by heavy rain.

In response, Laver tempered his aggression, and exploited his speed and wicked spin, made even more devilish on the uneven surface. At key moments Laver had reached tough shots, then found the balance to hit running lobs over his younger but slower, opponent.

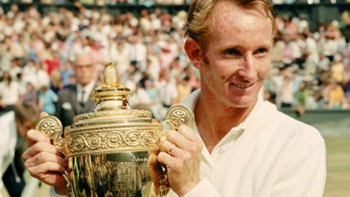

After losing a hard first set, the ruthless Laver took the next three, 6-1, 6-1, 6-2. Unlike 1962, Laver had got there without an attack of nerves like the one that had nearly downed him in the final match of the Slam seven years previously.

When it was all over, the winner of a second Slam stood facing Roche and did for him a crazy thing.

"I was in the air. What's this? I was leaping the net in classic fashion." Now this man felt a special aversion to show-offs, "bloody gloating high jumpers." But for once, Laver found that his built-in restraint had been released, and he was air-born.

It took some moments for his heart and brain to take in what he had done. By the end of the second Grand Slam, in greater and lesser tournaments, Rodney George Laver had won a record of 30 consecutive matches.

Though Laver was thirty-one when he won the second Slam, and was to keep the No. 1 world ranking for a further two years, he was never to win another Grand Slam title.

Laver's Game

What were the factors in Laver's game that led to two Slams, and in between, dominating pro tennis in the pre-Open era?

The power and flair of Laver's strokes were backed by flexibility of game plan and a quiet--and often underrated--court intelligence. This allowed him to play with all court strategy.

He had the uncanny ability to hit winners off winners. Richard Gonzales said the greatest difficulty in playing Laver was that he hit his best shots when you least expected them.

But he could become a Rosewallian brick wall, and hack and scramble with the best of them. Don Budge put it simply. The mature Laver had every shot and no weaknesses. But it was more than just the shots. Whenever, Rod Laver walked on to a tennis court, he felt that he'd nothing to lose. "Tell yourself to hit the ball," Laver later said. "You can only lose, and losing isn't the worst thing that can happen to you."

He knew that the game he loved was just a game, and his ultimate challenge was to retain the humility with which he started playing it. In the strangest way his success at that task explains much of why he became possibly the best player who ever picked up a tennis racket.