Bizarre Rivalry:

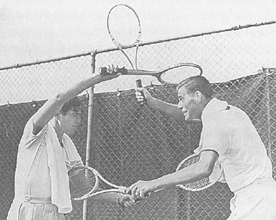

Bobby Riggs and Frank Kovacs

Tom LeCompte

After his devastating loss to Don McNeil in the 1940 Final at Forrest Hills, Bobby Riggs was determined to regain the title in 1941. But McNeil was not the only player or even the most challenging player standing in his way.

That was Frank Kovacs, the man the press called the Clown Prince, but who according to contemporaries, had a much darker side. (Click Here to read more about Kovacs game, personality, and gamesmanship.)

Dealing with Kovacs' dazzling shotmaking was one thing. Contending with his bizarre and even potentially criminal behavior was another.

How far would Kovacs go? If the accounts of witnesses can be believed, Kovacs drugged Bobby Riggs before a national final in hopes this would cause him to default.

Litany of Outrages

Everyone knew that, in general, if things were not exactly to Kovacs' liking, or perhaps even if they were, he was liable to simply walk off the court.

Gardnar Mulloy recalled a match in which Kovacs was having a difficult time against a low-ranked player. Playing in ninety-degree-plus heat, Kovacs suddenly decided he'd had enough.

He dropped his racquet, held his head in his hands, and claimed to be suffering from sunstroke. Defaulting the match, Kovacs was carried off the court into the dressing room, where he was laid down.

He immediately sat up and quipped, "Thanks for the lift, boys," and left the grounds.

And it seemed that whenever Bobby and Kovacs faced each other, Kovacs went out of his way to devise ways to upset Bobby. In Miami, for example, Kovacs and Bobby were set to face each other in a best-of-five-set final.

A shaggy-looking Kovacs, who decided to let his beard grow during the course of the tournament, goofed off initially, mugging it up for the crowd, hitting trick shots, and basically handing Bobby the first two sets. After deciding to play seriously, Kovacs put up a fierce struggle to pull out the third set, 8-6.

At this point the players were given a 10-minute rest break. As they walked off the court to take their break, Bobby, wary of what Kovacs might pull, warned the umpire, "I'm going to stay right here during the rest period. This tournament has a ten-minute rule for intermissions, and I'll be ready to play in exactly ten minutes. You'd better tell that to Kovacs."

The umpire leaned over and notified Kovacs that he had to be back on court in 10 minutes. Kovacs listened carefully and nodded, then walked off the court, presumably to go to the locker room.

Ten minutes passed and Kovacs was nowhere to be seen. Bobby reminded the umpire of the rules, but was convinced to wait.

More time passed and there was no sign of Kovacs. Someone in the gallery actually came forward to say he saw Kovacs get in a car and drive off.

Fuming, Bobby turned to the umpire to ask for a default, but was asked to be patient. "All these people paid a lot of money to see you two play."

After half an hour Kovacs bounded onto the court. "We'll I'm ready!" he announced cheerfully, bowing apologies to the gallery. A seething Bobby refused to acknowledge Kovacs and his anger negatively affected his game.

When Kovacs jumped to a lead in the fourth set, Bobby briefly fought back, but Kovacs' fierce hitting prevailed, 8-6. In the fifth set Bobby ceased trying and let Kovacs run away with it 6-1.

Escalation

The one-upsmanship between the two players now spilled off the court. Bobby began needling Kovacs over his feigned "heat stroke." For weeks he taunted Kovacs saying that he, Bobby, would never abandon a match under any circumstances.

The rivalry reached a shocking low point at the National Indoors in Oklahoma City, including what might have been dangerous criminal behavior by Kovacs. As recalled by Gardnar Mulloy, all week Kovacs keep telling Bobby what a great player he was and how wonderful it was that he would never default no matter how ill or injured.

The two players reached the final, and at dinner the evening before Kovacs continued his effusive flattery. Suddenly Bobby became violently ill and immediately left the table to return to his room.

He was up most of the night in pain, and woke up the next day with a splitting headache. Still he was determined to play.

Before they went on court, Kovacs began telling Bobby how sorry he was, telling him it was too bad he would need to default, and wasn't it a shame to break such a splendid no-default record?

Bobby was in no condition to play tennis, but would not default. In an attempt to reduce the painful glare of the overhead lights inside the auditorium, Bobby rubbed lampblack under his eyes.

He also decided to end points as quickly as possible by charging the net at every opportunity. But Kovacs passed him at will, leaving Bobby to shake his head despondently.

On the changeovers, Kovacs solicitously asked, ''Are you sure you don't want to default Bobby? You sure are pale." Bobby never answered. By the time Kovacs won the match, 6-4, 6-0, 6-2, Bobby could barely stand.

Months later, according to Gardnar Mulloy, Kovacs admitted to him that he spiked Bobby's drink the night before to make him ill, if true one of the most malicious actions against an opponent in tennis or any sport.

Bobby, however, never made much of the incident, even though it became common knowledge among the other players. Perhaps Bobby refused to believe Kovacs was really immoral enough to do it, or perhaps he decided to take his revenge out on the court.

Whatever the case, Bobby knew Kovacs' brilliance was matched by his tendency to self-destruct. Taking careful mental notes after each match with Kovacs, Bobby prepared himself for what he expected to be an ultimate showdown.

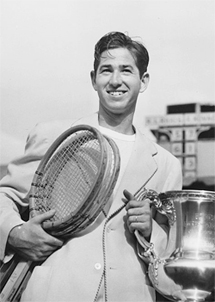

On pure tennis ability, he felt reasonably sure he could hit the ball on even terms with Kovacs. But he was dead sure he could outthink and outfight him. By summer of 1941, Bobby was playing the finest tennis of his career. He drew even in his rivalry with Kovacs at four matches apiece.

No longer considered a retriever, Bobby had turned into an all-court player. He mixed his incredible touch and finesse with power and a dead-on instinct for the kill, moving to the net without hesitation and decisively putting away balls.

Tactically, he was unequalled. He could match his opponents shot for shot, neutralize their biggest weapons, frustrate them with a mind-bending variety of shots, and surely and steadily break them down. Not only that, but Bobby could adapt to any surface.

Don McNeill, meanwhile, who had beaten Bobby in the 1940 Forrest Hills final, had started 1941 as the nation's No. 1 player, but had fallen from real contention. He lost all of his matches against both Bobby and Kovacs running up to championship in 1941.

Despite his fine play all season, and despite being the top seed ahead of Kovacs and defending champion McNeill, Bobby was far from the fan favorite.

There was, in fact, a palpable sense of disappointment when it was revealed that Kovacs and McNeill were in the same half of the draw. There would be no final between the hard-hitting McNeill and the erratic though vastly entertaining Kovacs.

A Year-Long Mission

Bobby played with grave seriousness the entire tournament, which was the culmination of a year-long mission. There was no mugging it up for the crowd, no all-night poker marathons. Nothing was going to distract him from his goal. During his first three matches, he did not drop a set.

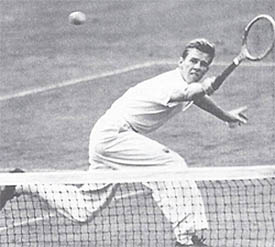

In the quarterfinals, he rolled past Frank Parker, setting up a semifinal match against Ted Schroeder. Bobby had never lost to Schroeder, and twice that season had defeated him without dropping a set. Unlike their previous meetings, this match was a dogfight, but still Bobby eked out a victory in five sets, 6-4, 6-4, 1-6, 9-11, 7-5.

In the other semifinal, Kovacs dismantled McNeill, and most experts predicted he would go on to win the tournament. On a blustery day at center court at the West Side Tennis Club, Kovacs wasted no time trying to get under Bobby's skin.

"Does the wind bother you, Bobby?" Kovacs asked as the two walked onto the court, remembering his straight set win over Bobby at Southampton a year before on a windy day. "No, I love it," Bobby answered, throwing Kovacs' provocation back at him.

Actually, Bobby hated the wind. He struggled to adjust, and Kovacs took the first set, 7-5. After settling down, Bobby started mixing slow, spinning floaters with deep, groundstrokes and acute angles to disrupt Kovacs' rhythm.

The tactic worked. Kovacs' game began to come apart. After each miss, Kovacs pressed harder, but his forehand kept missing, and he couldn't get to net without it.

Meanwhile, Bobby started taking advantage of Kovacs' short, undercut shots to come into the net himself, where he cut off Kovacs' pass attempts with unbeatable volleys. The crowd, which had backed Kovacs from the outset, started to get more vocal, but the cheers did little to help him. Bobby ignored the gallery and calmly won the next two sets 6-1, 6-3.

The umpire then called for the customary 10-minute intermission before the fourth. Bobby knew if Kovacs went to the locker room his coach, George Hudson, would have a chance to advise Kovacs to slow down his game and reduce his errors.

Bobby knew Kovacs was high-strung, but that given a good rest and a quiet talk with Hudson, he likely would come out a different player. While Kovacs sipped from a bottle of soda, Bobby picked up a towel and dried his hands and face.

"You look tired, Frankie," Bobby said pleasantly. "Probably want to go in and lie down a while, don't you?"

"Who's tired?" snapped Kovacs. "Not me. Let's get out there and finish this."

The ploy worked. Back on court, Kovacs' game continued to unravel. Occasionally, the "Clown Prince" pulled off an incredible pass or world-beating drive, but most of the time Kovacs seemed bewildered and dejected.

He struggled to hold his serve, and Bobby kept him constantly under pressure. With Bobby serving up 5-3 in the fourth set, Kovacs fell behind love-40. Tired, frustrated, and desperate to end the match, Kovacs hit his next return far up into the stands, conceding the title.

Bobby had finally gotten the best of Kovacs. It was also a turning point in Kovacs career. It was his first and last Grand Slam final.