Forest Hills and

the Dream of the Tour

Tom LeCompte

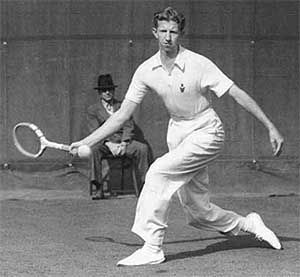

Bobby Riggs came to Forest Hills in 1939 as the Wimbledon champion. As the top seed, the U.S. Championship was his for the taking. Bobby roared through his half of the draw, dropping two sets en route to the final.

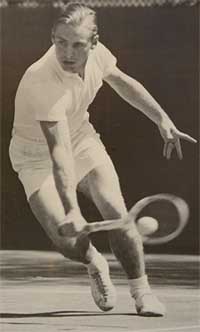

Meanwhile in the bottom half, a hot newcomer had emerged over the summer: Welby Van Horn. The youth's thundering serve and powerful volleys were drawing inevitable comparisons to Ellsworth Vines and Don Budge.

Van Horn slugged his way through his half of the draw, with three five-set matches including a comeback against John Bromwich in the semifinal, recovering from two sets down to win, 2-6, 4-6, 6-2, 6-4, 8-6. (For Welby’s amazing teaching system articles, Click Here.)

Despite fans' hopes for a new young gun to take the place of Budge, in the final Bobby had the answers to Van Horn's power. Van Horn's cannonball serves seemed to come back harder than they were delivered. When Van Horn rushed the net, Bobby passed him, and when Van Horn hung back Bobby came in on the attack.

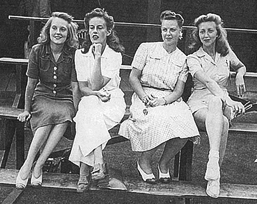

Bobby was in his words "able to control the match at will," winning 6:4, 6-2, 6-4. On hand to witness Bobby's achievement was his new girlfriend Kay Fischer. It should have been a triumphant victory for Bobby, capping a truly great year.

But, with attendance off because of competition from the 1939 World’s Fair (ironically held at the site of the current U.S. Open) and growing worries over the war in Europe, Bobby's first singles title at Forest Hills went virtually unnoticed. Sadly, wrote Allison Danzig, this "was probably the last big national tournament of international representatives until the roar of cannon shell no longer drowned out the ping of racquets in the Old World."

In October, Nazi bombs crashed down on Wimbledon, blowing a hole through the Centre Court roof and taking out a section of seats. There would be no tournament there until 1946.

For a time, Roland Garros in Paris was used by the occupying Nazis as a concentration camp for Jews being shipped to camps in the East. In Australia, the Davis Cup was stored in a bank vault, not to be seen for six years.

Bobby later joked that he was the world's longest reigning Wimbledon champion, but truly the timing of world events could not have been worse for his career. In all sports, the careers of an entire generation of players were cut short by World War II.

Despite all the criticism and ridicule of his game, Bobby was now the No. 1 amateur player in the world, earned legitimately through hard work and determination. He was 21 and had been training since he was 11. He had achieved everything he set out to do.

On Dec. 9, 1939, Bobby and Kay married in Chicago in a small ceremony at Kay's home. Bobby loved Kay. She was someone willing to completely dedicate herself to him and his goals.

Whatever personal goals Kay may have had were subordinated. The day after the wedding, she learned exactly what it meant to be married to Bobby. Bobby was back on court, competing in the Chicago Indoor City Championships.

He played a total of 15 sets in singles, doubles, and mixed doubles. Outside, It was bitterly cold. Inside, it wasn't much warmer. Kay sat huddled in a fur coat inside a freezing armory, watching her new husband.

Now that he was the No.1 player in the world, it was time to cash in on his standing as the leading gate attraction. Following his wins at Wimbledon and Forest Hills, he played more tournaments and exhibitions than nearly any other top player.

The winter circuit offered a good opportunity to pick up some extra cash, and no player was more adept at exploiting the expenses system and wringing money from tournament directors--in many cases setting the standard for other top players to follow.

In fact, for Bobby it was a point of personal pride. If another player managed to extort a given sum from a tournament director, Bobby made sure he got at least the same deal. Gardnar Mulloy recalled one tournament in Florida in which Bobby sat at the gate collecting the money from the ticket-seller every time an admission was sold.

After a few short weeks, Bobby built up a respectable bankroll. His goal now was to turn professional. The best players were in the professional ranks--Don Budge, Ellsworth Vines, and Fred Perry-and Bobby wanted a shot at them.

With Wimbledon, the Davis Cup, and many other major international events suspended because of the war, Bobby figured all he had to do was successfully defend his title at Forest Hills to gain an invitation to join the pros.

Bobby and Kay drove in their Buick 15 tournaments, with Bobby winning nine. But the hottest player that year was Don McNeill, the hard-charging collegian from Oklahoma. He and Bobby had played against each other four times that season, with each man winning twice.

In the Forrest Hills semi-final Bobby played Joe Hunt winning after five long, hard-fought sets, 4-6, 6-3, 5-7, 6-3, 6-4. But it had taken nearly everything out of him.

Earlier in the week, Bobby had come down with a chest cold, and as the tournament progressed it had gotten worse. Meanwhile McNeil defeated Jack Kramer in the other semi-final.

A doctor advised Bobby not to play the final. The night before, Bobby was running a fever, Kay recalled. She put Bobby to bed early and opened a window in their hotel room to let in a breeze.

Overnight, it started to rain and became very cool. When Bobby awoke the next morning, he felt even worse.

At the West Side Tennis Club, a decidedly pro-McNeill crowd was on hand, eager to see the rangy Oklahoman beat the puckish Bobby, whom one reporter characterized as "a dead end kid from the wrong side of the Los Angeles railroad tracks."

It was windy, and the rain from the night before made the court slick and slow. Minus his usual cheerful demeanor, the defending champion gravely took the court. He had defeated McNeill just a couple of weeks earlier on grass, but in a long battle.

Bobby surprised himself at how well he played this day, or rather, how well he felt and playing his usual game, hanging back, he won the first set, 6-4.

Given his flu, Bobby dug in and gave it everything he had, winning the second set, 8-6. But the effort clearly drained him. His game fell apart, and McNeill blasted his way to win the third and fourth sets, 6-3, 6-3.

By now, the crowd was completely involved in the match, shouting and clapping at the efforts of both players. At 4 all deuce in the fifth, McNeil served and rushed the net, hitting a sharply angled crosscourt volley into Bobby's forehand court. At first, the linesman indicated the ball was out, and a simultaneous cry from the gallery followed: "Out!"

But then the linesman held down the "safe" signal, indicating the ball was good. Unbelieving, Bobby walked up to the linesman and cried out, "For the love of Pete!" This was the harshest language fans heard from Bobby on court. But the linesman held firm, and Bobby, without any show of disappointment, accepted the decision and walked back to return serve.

After Bobby held serve to knot things at 5-all McNeill saved a break point and held. With Bobby serving at 5-6, McNeill returned serve with a drop shot just over the net with lots of backspin.

Bobby rushed to the net and managed to put the ball back in play, but it was so close to the net when he hit it that he had trouble stopping in time. He used body English to keep his shorts from grazing the net, but umpire Dwight announced the point was McNeill's because Bobby's foot had touched the net.

McNeill saved a game point by running down a volley to his forehand side, catching it just before it hit the turf and flicking it for a brilliant crosscourt pass. It was, recalled McNeill, an "impossible" shot, "the best I'd ever hit in my life."

At match point Bobby hit a half volley off his shoes that caught the tape and fell back to Bobby's side. Game, set, and match. Beaten and exhausted, Bobby managed to leap over the net to congratulate the new champion.

Bobby never made excuses, he never complained publicly about the two calls that may have cost him the match, or about his illness. With nothing but sincere congratulations for the man who vanquished him, he said, "Don played great tennis that day, and deserved everything he got."

The match was trumpeted as one of the finest ever at Forest Hills. Wrote one writer: "Never did a champion lose his crown more gracefully than did Bobby Riggs."

It was a bitter loss as it cost him a spot on the pro tour against Budge. But his heroic effort and the complete dignity with which he carried himself had earned him something perhaps greater, something he had never had up to that point: respect.