The Sissie Game

Tom LeCompte

Bobby's father, Gideon Riggs, Jr was a fundamentalist minister who moved with his wife Agnes from Tennessee to Southern California. He took a single, struggling congregation in a revival tent and grew it into a prominent church with dozens of congregations across the state.

Although his father lived most of his 84 years in Los Angeles, Gideon never really left his boyhood home of Tennessee. A farm boy at heart he belonged to a different time and place. Bobby, born and raised in Los Angeles, came to embrace all the city represented—the energy, the newness, the opportunity, the narcissism. The chance to create yourself.

Unlikely

Bobby was not tall, handsome, and glamorous. Short, cocky, disheveled, with a gait often compared to a duck's, he never cut the figure of a world-class athlete.

As one friend put it, "If you were in a restaurant and someone pointed over to Bobby and said, 'See him? He's the number one tennis player in the world,' you'd say, 'Sure. Have another drink.'"

Bobby admitted as much. "People have said to me that I must have been a miIlion-to-one shot to become a world champion."

With his mother busy cooking, cleaning, and washing, and his father preoccupied with the church, much of Bobby's upbringing fell to his older brothers. "They handled some of the authority," Bobby said, "but what they mostly handled was my whole athletic program."

The house was off limits to noisy youngsters. The family's social activities revolved around the church, so athletics became the boys' primary outlet. A converted garage behind the house became their clubhouse, with a basketball hoop outside and a Ping-Pong table inside.

In the plentiful California sunshine, sporting overalls and bare feet, the Riggs boys spent nearly every waking moment engaged in contests of one kind or another: foot races, table tennis, boxing contests, shooting baskets. The constant activity also made it a headquarters for children in the neighborhood.

Bobby's brothers, particularly Luke and John, seven and eight years older than Bobby, taught him how to punch and jab, how to run and jump and to shoot tops and marbles, how to go out, cut left, cut right, come back, and catch a pass, and how to swing a baseball bat.

Though small for his age, Bobby had natural gifts of speed, agility, strength, and coordination. Bobby's earliest memory was of running a race set up by his brothers against a neighborhood boy a year older than him.

Things changed for Bobby in 1924, when his eight-year-old brother, Frank, died in a freak playground accident. As Bobby recalled, Frank was halfway up a slide when the class bell rang. Frank ran to the top of the slide, toppled off, and hit his head.

His brother John, then nine years old, was called out of class by the school principal, who told him about the accident. Frank was conscious and seemed okay, but the principal wanted John to walk him the few blocks home, just in case.

About halfway home, Frank passed out and John carried his younger brother the rest of the way. Agnes put Frank to bed and called the doctor, who did not insist on seeing the boy immediately.

"Why can't Frankie come out and play?" young Bobby asked after school, wondering why Frank was in bed so early. Overnight, a blood clot formed in his Frank's brain and he never regained consciousness.

Frank, tall and strong, had been expected to be the star of the family, John said. With his death, attention eventually turned to young Bobby.

Bobby was spoiled as a result of the tragedy. "I guess because of Frank they gave me more attention and love and affection than they normally would have," he said. Being the baby of the family also meant Bobby inherited everything the others outgrew, from clothes to athletic equipment.

The True Education

But if Bobby felt spoiled it wasn't all by his parents. Frank's death meant the attention given to Frank by his older brothers now turned to Bobby.

In the clubhouse, Bobby received his true education. His brothers taught him how to compete-how to be faster, tougher, smarter, and more athletic than his peers. They'd test his ability, offering incentives--a piece of candy or a ticket to a baseball game--and then pit him against older, stronger kids.

They might give his opponents a handicap, allowing them a few yards head start in a footrace. "Never give up;' they told Bobby. "It's all right if a better man beats you, but it isn't all right if you quit."

As another reward, his brothers would sneak him into University of Southern California football games, where John and Luke ran a hot dog stand. They would hide tiny Bobby inside a cardboard box, telling the ushers it contained extra supplies.

Bobby relished the attention he received, and actually enjoyed his brothers' gladiatorial challenges. He was a whirlwind of energy, always in motion, always looking for something to do, something to play. He was also a nonstop chatterbox, a natural ham who loved being the center of attention. The fierce desire to win that his brothers instilled in Bobby became a life force for the young boy.

Competition drove him to develop an intensity few could match. No matter what the sport or contest, Bobby would master the basics of a game as well as the subtleties and strategy required to win.

One year, his brother John taught him how to toss cards into a hat. Bobby spent hours perfecting it, to the point where he could sink 20 out of 20.

When he wasn't competing, he'd practice by himself, honing his technique or figuring out different ways to win--even devising entirely new games he might play. Each year he'd add to his repertoire, learning new games, perfecting old ones.

Early Gambling

Bobby loved all games--marbles, dominoes, pool, backgammon. Early on he also picked up a penchant for gambling, beginning with pitching coins to a line and playing penny-ante poker with his brothers in the shack.

"Every once in a while, Dad would catch us with the cards and would tear them up and give us another lecture on the evils of gambling," Bobby wrote. "But I'm afraid the lesson was lost on me."

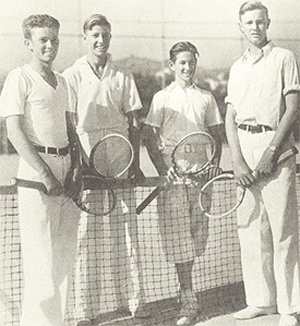

When Bobby was 11 his brother John tried out for the high school tennis team, a team Bobby would play on himself in a few years.

Bobby became fascinated with the game and begged John to let him try. As John tried to give Bobby his first lesson, a young woman playing on another court stopped to watch. It was Dr. Esther Bartosh, an anatomy instructor at the University of Southern California and the third ranked female player in Los Angeles.

"How old is your brother?" she asked John. "Eleven," John said.

"If he'd like, I'll be glad to try to teach him how to play." John knew who Bartosh was and accepted on Bobby's behalf.

John made sure Bobby understood his good fortune. "She'll be able to teach you a lot. You're a lucky kid."

The only problem was that Bobby didn't have a racket. The next day watching his brother practice, he saw one of his old teachers playing fetch with his dog with an old racket.

On one throw, Bobby beat the dog to the racket. He cheerfully approached the man and pleaded, "I can use the racket better than the dog can." Amused the man gave it to him. The racket was great at first, but since the dog had chewed up the wooden throat, it broke in two weeks.

The next move was vintage Bobby and his first recorded hustle. Bobby knew a boy on the block with a racket who never played because tennis was a "sissy" sport. Bobby traded it to him for 100 marbles. Then he and Bobby kneeled down to play and Bobby won all the marbles back.