How World War II Transformed

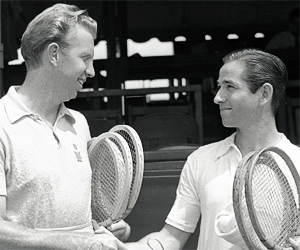

Bobby's Rivalry with Don Budge

Tom LeCompte

In 1941 Bobby Riggs regained the U.S. National crown he had lost the year before, defeating his bitter rival Frank Kovacs in the final. (Click Here.) But World War II was raging in Europe, and then on December 7 the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Suddenly no one cared much about tennis.

There was an abbreviated, sparsely attended pro tour in 1942 with Bobby, Don Budge, Frank Kovacs and Gene Mako. Due to lack of ticket sales many events were cancelled. Budge won the overall tour. He defeated Riggs 15-10 in head to head matches, and so maintained his position at the top of the pro game.

The next year pro tennis came to an end for the duration of the war. Bobby was drafted into the Navy. Budge had already joined the army, and virtually every other top player was in uniform as well.

It was three years before matches resumed. But when the war ended, Bobby emerged as the top player in the game. To the surprise of the tennis world, he reversed Budge's dominance over him, decisively defeating Budge in two newly created professional tourneys.

How did this reversal occur? The explanation lies in the untold story of the tennis that Bobby played during the war, including 5 matches with Budge, in an event staged by the armed forces on the island of Guam.

Navy Life

Used to the free-and-easy life of the tennis circuit where he bent or broke the rules to get his way, Navy boot camp in Waukegan, Illinois was an awakening for Bobby. An immediate request for a weekend pass to see his wife and young son was viewed as borderline insubordination.

Life in boot camp was a monotonous routine of menial tasks and petty rules for Bobby. Then, miraculously, Bobby was invited to play tennis with vice president Henry Wallace in Chicago. Being Bobby, he parlayed this knowledge into a series of sucker bets with his fellow servicemen who had just seen his weekend pass request turned down.

To Bobby's surprise, the vice president turned out to be a very good player. The 55-Year old vice president was a longtime tennis enthusiast and one of the best players among high-ranking Washington officials. He told Bobby, "I want to see if I can handle your serve."

Bobby expected to report the next day for another session, but the vice president said he wouldn't have time. So with a three-day pass in hand, Bobby spent the rest of his weekend at home with Kay and Bobby Jr.

Tennis in the South Pacific

Upon graduation from boot camp, he was shipped off to Pearl Harbor. Again fate turned his way. While many of his tennis friends and rivals saw hard action in Europe or the Pacific, Bobby spent the war giving tennis exhibitions and clinics to the troops. As for his gambling, it was an ideal environment--lots of men with free cash and plenty of spare time.

Bobby put on between three and five tennis exhibitions a week at hospitals, recreation centers, camps, and clubs, his opponents rotating among those near the top of the base tennis ladder, including Norman Brooks, the fourth-ranked player in Northern California, and Jack Rodgers, the second-ranked player in Texas.

The game proved incredibly popular on base, with long waits for courts and most play limited to just a single set. A base tournament in 1945 drew 158 singles players and 67 doubles teams.

Bobby's charmed run continued when Admiral Chester W. Nimitz transferred him to his new headquarters on Guam, where Bobby became Vice Admiral John Hoover's permanent doubles partner.

In 1945, with the war winding down, the .Army and Navy brass decided to stage a series of Davis Cup-style matches between the Army and the Navy. Guam was now home to four of the best tennis players on the planet. Don Budge and Frank Parker were both stationed at the Army compound on Guam, while the Navy had Bobby and his old doubles partner Wayne Sabin.

Path From the Shadow

Bobby knew that once the war was over he would have to fight it out to stay in the pro ranks, and that his stiffest competition would likely be Donald Budge. Three years older, Budge had so far dominated Bobby in numerous matches. Like everybody else, Bobby stood in awe of Budge's power and had lived under Budge's shadow.

If Bobby was to wrest the tour away from the great Budge, he had to prove to Budge that he could beat him. Moreover, he needed to prove it to himself.

He began devising a plan of attack. Bobby knew Budge had a terrific all-around game, but he also knew from experience that if there was a single weakness in Budge's arsenal, it was his forehand. Unlike his beautiful, flowing backhand, Budge's forehand was not a natural stroke, but an "educated" shot he adopted later under the coaching of Tom Stow in Oakland. Because of this, Budge's forehand was apt to break down under stress.

Bobby also knew Budge was vain about his game, and that he would never admit---even to himself--to the possibility he could lose. Because of this, Bobby suspected he might have let his training regimen slip while in the Army.

"I said to myself that the difference between Don Budge and me is who is going to come out of the service fit. So I said that I am going to work on my game and become a better player than I was before."

Bobby decided he had to quit looking at Budge as if he were invincible. He also had to improve his conditioning so he could endure a long match with Budge.

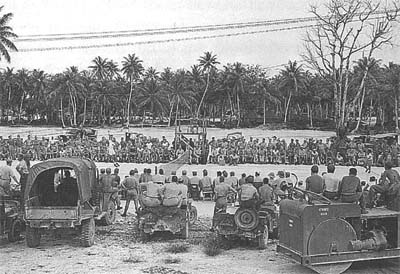

Given the rivalry between Budge and Bobby--the two best players in the world--and the rivalry between the two services, the matches took on the atmosphere of a heavyweight prizefight.

Thousands of dollars were bet. Thousands attended the matches, with many more listening to play-by-play broadcast over military radio.

The conditions for the matches were brutal, played under a blazing sun on courts carved from the island coral and surfaced with a mixture of broken rock and sand.

Because of the intense heat and humidity, Bobby and most of the other competitors played shirtless and in shorts, but the ever-proud Budge insisted on playing in the traditional white shirt and white flannel pants.

In the first match, Budge picked up right where he left off before the war, cracking his serve, hitting blistering groundstrokes, especially off the backhand side, and pushing Bobby all over the court. Near the end, Bobby simply shook his head and muttered, ''Ah, you're too much." Budge won 6-2, 6-2.

The next match was closer, but Budge won again, 6-4, 7-5. A disheartened Bobby came off the court thinking he'd had some chances, but simply could not capitalize on them.

But Bobby won the next two matches, 6-1, 6-1, and 6-3, 4-6, 6-1. Afterwards, Budge was in disbelief at losing two in a row to Bobby. The fifth and final match now had broader implications than just the pride of their respective services or entertainment for the troops. Whoever won would have a psychological edge over the other in any postwar contest.

"If I beat him today," Bobby said, "I'll know for sure I can beat him any time." On a brutally hot and steamy day, the two went at each other in a tense, seesaw affair. Knowing that he could not outgun Budge, Bobby took advantage of the conditions, working to make the points long to wear Budge down.

The two split the first two sets. As Bobby had predicted, he started to benefit from errors off Budge's forehand side. After more than two hours of chasing down balls, reaching for overheads, and dashing after dropshots, Budge could barely move. Bobby won 8-6.

For the first time, Bobby had beaten Budge in a series of matches he knew the great man badly wanted to win. Bobby had proven that Budge was human, that he did make mistakes. The matches with Budge, he would later write, gave him much needed confidence that carried over when he returned to the States.