Coaching Control:

The Measure of Success

Allen Fox, Ph.D.

When people are asked what attribute of the successful coach is the most important, answers usually include "knowledge of the sport," "personal relationship with the players," "organization," "commitment to the team," and the like. Of course all of these are valuable, but superseding all in importance is the need for control.

To be successful, a coach must, above all, be able to induce a player to do what he or she wants. Without control, a coach can have all the technical knowledge and great ideas in the world and it will do no good because it won't translate into changes in behavior. In fact, underlying much of the value of the other excellent attributes listed above is their role in augmenting the coach's degree of control.

Technical information is useless to a coach who can't make his players act on it. It is similar, in many respects, to the issues faced by parents of young children Most parents have the best interests of their children at heart and have a pretty good idea of what will help or harm them. Young children, on the other hand, are emotionally driven and simply lack the experience and judgment to make consistently correct and safe decisions for themselves. Of course they think they can, just like young athletes, but parents know they can't, and even the least knowledgeable parent usually has better judgment than a young child. It is much the same with coaches and their players. It may sound a little silly in the telling, but people of any age simply can't fathom what they don't know - if they could, they would already know it.

Tennis players are notoriously hard to move, and observing from the outside, you wouldn't think that it would be as difficult as it is. But the good ones often get as good as they do because they are strong willed. That can make them suspicious and resistant to input. This fact may not be apparent, but it is one of the things that makes coaching in tennis so challenging.

Great coaches gain control of their players in various ways, generally as a function of their personalities and particular inclinations and skills, but in all cases, they have it. However, the amount of control a coach develops or can develop will vary significantly with the coaching situation. For example, college coaching, junior coaching, and coaching on the pro tour are all significantly different. Let's take a look at what control means in each of these three coaching arenas. Afterward we'll look at some characteristics all successful coaches share. That could help you if you are a coach, or looking to evaluate or to find one yourself.

|

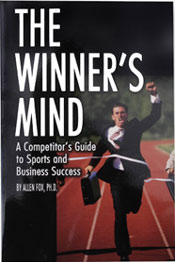

Stanford's Dick Gould: master recruiter and motivator. |

College Coaching

During my own college coaching days at Pepperdine University I watched the two best college coaches in the business run their teams in completely opposite ways. Glenn Bassett, the men's tennis coach at UCLA, was a no-nonsense disciplinarian. A former world-class player himself, Glenn had been a workhorse as a player. Soft-spoken but tough, Glenn was detail-oriented, organized, ran long, hard practices, and dominated his players with strict rules. Any player not doing as he was told immediately found himself on the bench.

Glenn did not talk much and rarely lost his temper or showed heated emotions, but his players quickly learned through his actions that he meant business. There was very little warm, fuzzy personal interaction with the players as individuals, although he did periodically work with each of them alone on court to zero in on technical weaknesses. Glenn's approach was a simple "my way or the highway." Everyone knew and understood a set of uniform, simple rules. And it worked, as Glenn's teams won 7 NCAA National titles.

Dick Gould, the tennis coach at Stanford University, could not have been more different. He was people-oriented and charm personified. With an arm around your shoulder, a warm smile, and an engaging, friendly tone of voice, Dick was extraordinarily persuasive.

He was the master fund-raiser and recruiter, raising enormous amounts of money for his program. Unlike basketball and football, tennis is not a revenue producing sport for colleges It costs the schools money, and they are somewhat tight-fisted when it comes to spending on tennis facilities. Dick used a portion of the monies he raised to build one of the finest and most lavish tennis facilities in the country. It made the players feel special and was a great recruiting tool. Gould became one of the most successful college coaches in any sport winning 17 NCAA team titles before he retired.

|

Gould built one of the finest tennis facilities in the country. |

Although he played varsity tennis at Stanford, Gould had not been a pro player and lacked some of Glenn's first hand tennis knowledge. But highly intelligent as he was, he knew enough. Compared to Glenn, Dick did not design demanding practice regimes. Nor did he set up a strictly-enforced system of rules. But Dick was the master recruiter and convinced the best players in the country to come to Stanford. With his team rosters populated by the best players, he did not have to teach them how to play tennis or how to work hard. They already did this. He just had to keep them happy and get into their minds so they would be ready to play their best in the matches.

Gould had an uncanny instinct for how to move his players around psychologically. He handled each player differently, as required by the situation and the individual's personality. For example, in the same circumstances, he might slap one player on the back and kick another in the behind. He could be as tough or gentle as the situation and player demanded.

Dick instinctively sensed how to motivate his players and entice the best performance out of each at the most important times. On these occasions, he made them want to play their best and set an emotional tone that gave them the confidence to do so. When the NCAA Championships rolled around at the end of the season, his players were invariably ready to produce their strongest performances.

At times both Bassett's and Gould's players would, as college players at any school are wont to do, grumble about their coaches. Glenn's players would complain that the practices were too hard, boring, and repetitious, and that he was too rigid in his decision-making. Gould's players, would grouse that the coach didn't know enough about tennis, and was too soft and let the players push him around.

|

The job description in college tennis: win championships. |

But, of course, the players didn't completely get it. The job description of each was to win national championships and both were unusually successful at doing just that. The heads of athletic departments may talk about character development and academics, and these issues are certainly to be found somewhere on their priority lists, but looming right at the top of those lists is the coach's ability to win. And within the constraints of morality and rules, it doesn't much matter how. Despite their differences, they were both formidable adversaries. I know because I coached against both of them many times while I was the men's coach at Pepperdine.

My experience in establishing control of my players was based on my own personality and was therefore different from either Glenn's or Dick's. My style was a "leader of the pack" strategy, to lead by force of personality from the inside. This is a tricky approach, but in pulling it off, I had certain advantages. I was already in my mid-thirties when I first started coaching and had a wide range of experiences. I had my undergrad degree in physics and my doctorate in psychology from UCLA; I had run my own investment company; I was teaching some classes in psychology and statistics at Pepperdine; and I could still play, having won the NCAA singles and doubles and been a quarterfinalist at Wimbledon.

In my early years I could still go out and, for at least for a set, beat almost all of the guys. In my mind, at least, I was a better player than any of them. And so I wasn't intimidated by guys that were playing college tennis. Most importantly, I knew a lot more than those guys in a wide range of areas. I knew it, and they could sense that I knew it.

I was just very confident intellectually. If players challenged me, I usually got the better of them by using friendly but slightly aggressive, pointed humor. They'd end up feeling silly. And the other guys would think it was funny. For this reason this most of the players chose not to mess around with me too much.

Siamese Twins

In college tennis, the leverage to establish control stems from the Siamese twin nature of the relationships between players and coaches. The players have power over the coach because the coach wants to win and needs good players performing at the peak of their ability to do it. The coach isn't going to win if he loses his better players or antagonizes them in such a way that they don't give their best efforts in matches. Moreover, one grousing, disgruntled player can set a negative tone for the team, infect the rest of the players, and do a lot of damage.

On the other hand, the coach also has his weapons. He controls the scholarships and the positions on the team. The coach can take away a scholarship, move a player down in the playing order, or bench a player. So the coach and his or her players have leverage over each other. This is quite different from junior or pro tennis as we will see.

|

Who has who in the Siamese relationship between coaches and players? |

It can become a bit of a game of chicken. Who's got who? Who's willing to go to the mat? Who believes whose threat more deeply? It doesn't usually get that far, but a coach must be prepared for nuclear war. In this case, nuclear war is where the player loses his scholarship and the coach loses the player. Fortunately, it rarely comes to that. But at the very least, as a coach you want the players to think that you're willing to explode the bomb it if pushed too far. Whether you are or not is another question.

The actual balance of power is rather close, with the coach having a bit the better of it, but on a day to day basis a strong coach is generally able to impose his will because he has a great deal more experience dealing with players than the players have dealing with coaches. In addition, the coach has more options for action, and, most importantly, a tremendous advantage psychologically.

One situation where the power struggle rears its ugly head is when, during a match, a player is losing emotional control and becomes either excessively angry or is down and negative, both of which states are ways of tanking. Watching from the sideline, the coach knows that if this continues, the player will lose for sure (These are the key negative emotions that all coaches work to control in their players.) Strangely, as much as the player might be in the process of throwing the match away, he is loath to have the coach come out and take him off the court He is intent on blowing it himself.

What is a coach to do? In many instances just coming out on the court and talking to the player can pull him out of his funk. Unfortunately, this sometimes doesn't work. My next move, in this case, was to warn my player that if he could not turn his head around, but rather continued to act in this self-destructive manner my next venture onto the court would be to default him and concede the match.

On several occasions I was actually forced to carry through on my threat. I must admit that I generally tried to do this early in the season when the matches were usually against weaker opponents and where one default was unlikely to cost us the overall team match, and, moreover, when its salutary effects on the team would have the rest of the season to operate. (On one unfortunate occasion my assessment was wrong and it did cost us the team match, but such are the risks of enforcing coaching control.) In any case, it impressed that team that I meant business when I said I was going to do something.

Junior Coaching

The dynamic is different in junior tennis. These relationships are not based on the same type of reciprocal leverage as in college tennis, at least in the early stages of the player's development. Here the coach is rather firmly in charge, since the coach is the teacher, and the junior is the novice pupil who is quite replaceable if he or she gets too far out of whack. But when the juniors reach the higher levels of national prominence and look like they have a shot at making it on the pro level the leverage shifts toward the player. Here, the bottom line is that the coach is getting benefits from the player in the form of elevated status in the coaching arena that he or she may be loath to relinquish in the event the player decides, for whatever reason, to go elsewhere.

In the beginning it can be fairly easy for the coach to establish control. If the coach simply handles himself with confidence and has a reasonable amount of knowledge, the kid will generally buy into his or her authority. As a general rule, people are attracted by certainty and are uncomfortable with ambiguity. So coaches that carry themselves with confidence and speak in a positive manner will usually have their students accept their instructions without complaint, even if the coach is not technically exact in his knowledge.

Of course the kid will rarely do everything the coach asks, but will generally follow most of the coach's directions. This is much to the pupil's benefit. Young players tend lack perspective along with technical information. The coach is, at least, a grownup. He has an outside view, and doesn't have to be the greatest coach in the world to be able to do a great deal of good.

The tug of war starts when the player starts to improve and have noticeable competitive success. This raises the coach's stock amongst his or her peers. Tennis is an incredibly hierarchical game, even at lower level junior tournaments. So if the coach has the best player in the tournament, he gets to enjoy the pleasant experience of becoming somebody (at least in that little arena). The coaches of the best players automatically have higher status than the coaches of the weaker ones. It may be unjustified in that the situation may have little or nothing to do with the coach's actual coaching ability, but that's human nature. We live amongst hierarchies and are always rating ourselves as to where we stand relative to everybody else. And most of us are looking to move up.

Thus as the player wins more matches, the coach gets something out of it besides a simple hourly stipend. And the player starts to feel that. As the coach's status rises as a result of coaching a particular player, the leverage starts to shift towards the player. And the more the player senses that the coach is benefiting from him, the more the leverage shifts away from the coach. Now the coach has some risk of loss if the player decides to go to some other coach. This is where the coach becomes tempted to pander to the player and reticent to say things that the player won't like, not particularly helpful to the player's development, but a fact of life.

The major, name coaches are in a somewhat of different position from the other coaches. They are famous and celebrities in their own rights, much of this fame having come from coaching highly ranked players in the past or having been highly ranked players in their own rights. Here I am referring to coaches like Robert Lansdorp, Nick Bollettieri, Brad Gilbert, Jose Higueras, etc. These big-time coaches have immediate credibility and leverage with their players. And as long as the coach remains more famous than the player, the balance of power remains with the coach. But even these coaches are ultimately at risk of their players deciding to move on to greener pastures.

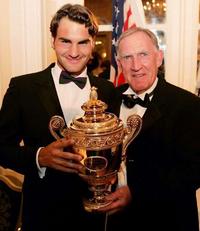

As an example, consider the development of the relationship between Maria Sharapova and Robert Lansdorp. At the beginning, Landsdorp was the bigger celebrity and had the credibility of having coached a horde of champions. Sharapova needed Lansdorp's help and wisdom. So Lansdorp was initially in firm control If he said "jump," Maria's only acceptable retort was "how high?" But that was soon to change, particularly after Maria won Wimbledon. At that time, she became a huge international celebrity. Of course Lansdorp is acknowledged, more than ever, to be a great coach, but a Wimbledon victory under a puplil's belt has a tendency to make the pupil's answer change from "how high?" to "why should I?" A Wimbledon championship and worldwide acclaim will naturally alter the balance of power, and not in favor of the coach.

|

Control can become a question of who is more famous, the coach or the player. |

There are many reasons why players make sudden coaching moves, abandoning coaches that developed them for "new opportunities." One reason is that they have heard everything their old coach has to say so many times that it no longer makes an impact. They may feel they have already learned everything their old coach has to teach them. Then again, as the player's stature increases the player becomes more attractive to "name" coaches and academies. They are tempted to think that the new coaches have ingenious tricks to show them that are beyond the knowledge of their old coach from the neighborhood. Players are always looking for any edge that they think can help them move up the competitive ladder.

In this section, I have been talking mostly about the kind of control the coach gains through credibility and leverage. In a sense there is power and force involved in this type of control. But as I mentioned earlier in the section on team coaching, there are other ways for coaches to gain control in the relationships with players other than using force. As with team coaches, the people skills and personalities of the coaches can an important factor. Some people are simply extraordinarily adept at convincing people to accede to their wishes.

|

With few exceptions the pro player has the leverage over the pro coach. |

Pro Coaching

Coaching at the higher levels of the pro game is quite different from college or the junior coaching. Here, the employer is a name player and international celebrity to begin with and has virtually all of the power. The coach has minimal leverage. He or she has a job, and a well-paying one at that, but a job that can be terminated at the whim of the player. Thus, everything the coach asks the player to do must meet with the assent of the player. The coach is in no position to force the player to do anything. Both sides understand this. The coach isn't dealing with a wide-eyed 10 year old kid. He's dealing with an elite world-class athlete who is writing him big checks based on the perceived value of his services and the pleasure of his company.

Although the high level pro players have most of the leverage, they do not have all of it. The coach always has the option to walk. A top coach like Tony Roche, for example, may feel that he does not really need to be out on tour at this stage of his illustrious career, even with a champion like Roger Federer. Roche serves at his own pleasure and probably has a more balanced power relationship with Federer than most pro coaches have with their celebrity employers So might coaches like Jose Higueras and Brad Gilbert, but they are in the minority.

The coach has some limited leverage in other ways too, because the coach supplies certain things that make the player's life easier. Depending on the coach, he may be in charge of such things as: getting racquets strung, scheduling court times, lining up hitting partners, making travel arrangements, etc. Yes, he may also be helpful in scouting opponents, coming up with strategies for matches, giving soothing advice after losses, and setting up plans for his player's technical and physical improvement. But Roger Federer, for one, proved able to get along quite adequately in these areas without a coach at all. In many if not the majority of cases the coach's greatest value to the player is in the psychological, companionship, and life style areas. And in these cases, the power is largely in the hands of the players.

The general public may think that being a tour coach is a glamorous, powerful position as they watch the television cameras zoom in on the coach in the stands stroking his beard and looking intelligent while his player whips up on an opponent. I will admit that that part of the job would be fun. And hanging out in the player's lounge playing ping pong, eating catered food, and drinking free beers and fresh juice is also not terribly unpleasant. Yes, it all looks glamorous. But most of the job isn't, and I personally would find the constant traveling, pressure, and competitive grind unbearable if I had to do it week in and week out.

I've watched some of these coaches sitting on the sidelines as their players were getting destroyed on court and thought to myself, "This could be a real unpleasant dinner tonight." What would you, as a coach, say to your angry, frustrated, depressed player after he loses a number of close matches because his confidence is temporarily on hiatus? This is particularly problematic after he has heard you say, for the hundredth time, "Don't worry It will get better soon. It's about to turn around. You are playing fine but the breaks are just going against you. Etc." and your repetitious words are beginning to grate on his nerves as much as losing the matches themselves.

|

Brad Gilbert, one of the few coaches top players have actually come to depend on. |

Worse yet, from a coach's standpoint, are the cases where, at your suggestion, your player has been adding something to his arsenal - making some changes in his strokes, strategies, or shots. (Unfortunately, whenever a player makes such changes, he deviates from habitual, trained responses. This often results in the player going backward before going forward.) Now, for example, he's trying the new stuff on TV and getting destroyed, and nothing you told him is actually working. After the match you (the coach) are in the awkward position of having sit down with your potentially angry and emotional employer who blames you for his loss, and, over dinner, explain how these changes take time to jell. How are you going to handle it? How's your credibility doing at this point?

If the coach is really a genius, sometimes he can get into the player's head and game to such an extent that the player actually recognizes long term that he needs him to produce his best results on court. This takes an extraordinary coach - someone of the quality of a Brad Gilbert. Gilbert is outstanding as a coach because he has certain unique qualities. Not only is he very, very intelligent, but he also has that street-smart cunning that enables him to spot subtle weaknesses in opponent's games. His long and successful experience as a world-class player who was short on physical tools but long on mental ones taught him how to employ shots efficiently. Brad was able to pass this information on to Andre Agassi and to make an obvious, hugely positive impact on his game. Agassi didn't keep Brad around for all those years out of the goodness of his heart. Brad really helped him. In his work with Andy Roddick, Brad also made an immediate positive impact on his results, whatever may have happened later on. ( I know I talk a lot about Gilbert, so for the record I want to state that he is not a relative of mine I just admire and like him.)

At the higher levels of pro tennis my definition of the "control" exerted by the average effective coach is very broad. Here the coach can exert positive influence (i.e. control) but certainly is constrained from using any kind of force. Essentially the coach's job is to make the player happy. This may include making some small technical or strategic suggestions but the bulk of the efforts will go toward, as mentioned above, lifestyle and comfort enhancements. The coach mainly needs to make his player feel good and want to play --a matter more of people skills and touch than of technical expertise. This is a far cry from what people may think when they watch matches on TV and assume that the guy sitting in the box is some kind of a mastermind pulling the strings and controlling what the player does out there.

Establishing Control

It should be clear by now that when I speak of the effective coach's need for "control," I really mean "influence." And this may or may not involve any use of coercion or force. Depending on his job description (and I have identified vast differences here depending on exactly who the coach is coaching) and his personal talents, the coach will be obliged to use different methods to achieve his ends.

Despite these differences, there are certain behaviors and strategies that seem to work for most coaches, regardless of personality style. The most important of these by far is the coach's emotional investment in his team or player's performance. This is the level of the coach's hunger for excellence and willingness to expend unlimited effort in pursuit of competitive goals.

Players can feel the power of the coach's investment and devotion, and in return often feel obligated to respond in kind. In this sense, the coach supplies moral force, and this drives the athletes. Coaches can not fake this. The athletes sense it in the coach's tone of voice, body language, and facial expressions. And when the coach wants it badly enough, the athletes tend to over perform.

By the same token, if the coach is lackadaisical and casual about the process the athletes will tend to under-perform. Coaches who are insufficiently hungry for excellence lose moral force. They lose control particularly in a team situation. Coaches who are willing to pay the price in terms of effort and planning, earn the credibility to come down strongly on athletes who are not giving their best.

A second universally effective tactic is to be well organized, prepared, and self-assured Athletics is a risky business, and players recognize that no matter how well they train and prepare, they can never be sure of their performance on a given day. This uncertainty makes them gravitate toward the shelter of a coach who plans in advance and seems to be on top of all details. Athletes are comforted by a coach who comes to practice with a plan, and they feel insecure with coaches who fly by the seats of their pants. They want to believe that the coach has thought everything through, has good reasons for everything he or she does, has solutions for their insecurities and problems, and is confident in his or her plans, decisions, and programs.

A third method for enhancing coaching control, particularly with teams and younger, developing players, is to have frequent meetings to discuss goals and approaches to improvements Here the coach is working to bring the players views in line with his own.

Short meetings (a couple of minutes) can be useful every day before practice to establish a proper attitude for the day's work. Before the meeting coach should jot down on paper a couple of motivational ideas as to what he plans to accomplish this day and why the particular drills on the agenda are valuable. This helps to direct the player's thoughts and attitude in the right direction. If the coach doesn't do this and simply lets nature take its course many weaker-minded athletes will hit the court with a bad attitude. Or they will develop one if they start playing poorly. The coach will then have a difficult if not impossible time changing it.

|

Coaches like John Wooden can set an elevated tone that players respond to. |

A final suggestion is that the coach set an elevated tone for the practices and games. John Wooden, the legendary UCLA basketball coach, did this very effectively with his "pyramid of success." His pyramid stressed higher values such as self-control. patience, faith, poise, team spirit, cooperation, friendship, loyalty, , etc. This helped counter the anxiety caused by the athlete's uncertainty of outcome in important situations. Of course Wooden's "pyramid" is particularly applicable to team situations, but even individual coaches can profitably underscore higher values such as having the courage to maintain emotional control under adversity and taking pride in competing with 100% intensity, regardless of outcome.

Focusing narrowly on winning and self interest is generally stress-inducing because practitioners of this approach are doomed to frequent and emotionally painful disappointments. Concentrating on higher values and even on other people instead of worrying exclusively about one's self reduces the pressures of these uncontrollable outcomes. People who do this can come away from losses with less pain and this reduces the potentially debilitating fear of failure. Coach Wooden found that his players performed extraordinarily well in crucial situations when he stressed the likes of "poise," "self-control," and "team spirit" rather than "make the shot" and "win."