What I Learned From the Inner Game

Part 1

John Yandell

Recently I got a surprise email from Tim Gallwey, author of two seminal books, The Inner Game of Tennis (Click Here) and Inner Tennis: Playing the Game. (Click Here.) I'd never met Tim, but he'd been looking over Tennisplayer.

He apparently found it too focused on stroke mechanics. "What did you learn from the Inner Game?" he asked. The implication was not much.

I wrote back and said that like everyone else I knew that had read his books, they had inspired me and were consistent with my use of imagery in teaching. I also mentioned we had dozens of articles in the Mental Game section, some of them inspired by his work. (Click Here.)

I asked him if I could excerpt some of his work, or maybe he wanted to write some original articles? But I never heard back.

His question got me thinking though, what did I learn from the Inner Game? So I decided to begin this series to answer that question.

I first read the book in the late 1970s. I believe it is still the best selling tennis book of all time with something like 250,000 copies sold.

It caused a sensation. Everyone I knew was readying it and talking about it.

It was in part a repudiation of traditional tennis teaching, which was then, as it is in large part now, collections of verbal tips being fed to students by pros with baskets of balls. In a typical lesson, Gallwey wrote, the student's mind was churning with "six thoughts about what he should be doing and 16 thoughts about what he should not be doing."

Gallwey described the effect of his own traditional teaching on one of his students: "The muscles would tense around her mouth; her eyebrows would set in a determined frown; the muscles in her forearm would tighten making fluidity impossible..."

The same day he decided to try a different approach with a new beginning student. "I was going to hit 10 forehands myself and I wanted him to watch carefully, not thinking about what I was doing, but simply trying to grasp a visual image of the forehand. He was to repeat the image in his mind several times and then just let his body imitate."

After this exercise, the student "took a perfect backswing, swung forward racket level, and with natural fluidity ended the swing at shoulder height, perfect for his first attempt."

Gallwey's conclusion was "images are better than words, showing better than telling, too much instruction was worse than none, and conscious trying often produces negative results."

Gallwey went on to describe how he thought this same non verbal state described what was going on with high level players when they were playing their best. "There seems to be an intuitive sense that the mind is transcended."

"He is out of his mind. He is unconscious; he doesn't know what he is doing. He is not aware of giving himself a lot of instructions, thinking about how to hit the ball, how to correct past mistakes or how to repeat what he just did."

"Perhaps a better way to describe the player who is unconscious is by saying his mind is so concentrated, so focused that it is still."

For me reading this part of the Inner Game, dovetailed with what was happening with my own teaching at Golden Gate Park. I was one of the best 4.5 players at the park, but in the beautiful egalitarian spirit of the players there in the late 70s and early 80s, I mixed with and befriended the many higher level players who practiced there everyday, including many top college players and some who had played on the tour.

I began to watch their matches at the Park, and also follow them around and watch them play in Open level tournaments in Northern California. And virtually everytime after one of those experiences, I would play far better myself.

Other players at my level at the Park would tell me of similar experiences after watching pro matches on television. That took me back to when I was first learning the game around the age of 12.

My brother, a year younger than I, watched Rod Laver and Ken Rosewall play a match on our black and white TV and then went out to the neighborhood court and played the best tennis of our lives.

At about this time, I first started using video in my teaching. We actually had a state of the art Sony Betamax camera and recording deck.

I could film my own strokes, show them to my students, and then film them, comparing their strokes to mine and watching them absorb technical information visually rather than verbally. The result was often startling improvement.

During this same period, often to the annoyance of players on adjacent courts, I began teaching to music, rallying with my students, and again seeing cosmic jumps in their feeling for rhythm and timing.

I saw beginners and low level players go from 2 and 4 ball rallies to rallies of 20 balls and more. Some of my regular practice partners started coming to my teaching court and doing the same—often requesting we hit to their favorite songs. Time and time again we would play at higher levels.

This all led me to an idea that changed the course of my career. What if we could film the best players in the world, set that to music, and use that as a visual modeling tape players could use systematically over and over?

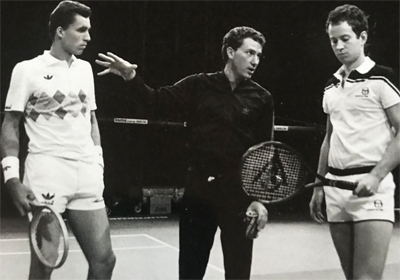

And so in 1983 and 1984, carried by no more than my inspiration, a series of serendipitous events lead to producing "The Winning Edge" with John McEnroe and Ivan Lendl.

That footage is still alive in our Music video section. Click Here for example to watch the groundstroke segment, set to Walking on the Moon by the Police, a song suggested by John McEnroe himself.

The rest of the music videos of these two legendary players are in that section of Tennisplayer as well. To this day I still get occasional emails from player and coaches who loved The Winning Edge.

Although I can't say there was a direct causal connection, this evolution in my work was consistent with what Gallwey had written. Maybe it was all part of the spirit in the air in those amazing days.

Stay tuned for more from Tim's work and his famous distinction between the two selves in every tennis player.