The Lessons of

Pancho Segura

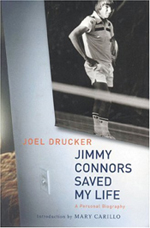

Joel Drucker

Coaches are the missing link between inquiry and understanding – none more so than Pancho Segura, the Hall of Fame coach and player who was ranked number one in the world for three years.

In the last installment of Caroline Seebohm's amazing series on Segura's life and career, she discussed his long-term relationship with Jimmy Connors and how he helped influence the development of Connors' game, leading to victories at Wimbledon and the U.S.Open in 1974, as well as other triumphs. (Click Here.)

In this exclusive article for Tennisplayer, I share the strategy that Segura imparted to Connors and hundreds of other players, based on both numerous interviews and my own experience working with him on court. This includes one of the ultimate drills ever devised for developing the skills and confidence required to play the style of game Pancho believed was most effective.

Over more than 30 years, Segura provided me with a remarkable tennis education, one that covered topics ranging from grips to the psyche of a champion. I was not the only person who benefitted from this man's extraordinary wisdom and generosity. There are likely hundreds of tales of players who wandered into Segura's orbit and became beneficiaries of his eagerness not just to instruct, but to engage in a two-way manner, rare for someone of such tremendous accomplishments.

Jimmy Connors had been Segura's prize student. Shortly after Connors won the National Boys 16s title in 1968, he moved to California to work with Segura. From Connors' teens to early 20s, the two formed a powerful duo. Connors' mother, Gloria, and grandmother, Bertha, had been his mentors, providing him with the fundamentals to become a superb, steady and deep-hitting baseliner. Gloria and Bertha had shown the boy how to sustain points. Segura taught him how to end them.

Segura relished the chance to study, understand, and then, break up his opponent's game. Here are the cornerstone principles: Assess. Apply Pressure. Play the Score.

Assess

Segura and I watched many matches together. "This guy, look at him, what do you think of his groundstrokes?" he'd ask me.

"Some pretty good topspin off both sides," I would answer.

"Maybe, but the wrong kind of topspin," Segura would say. "With that grip and that swing, he'll get tight and the ball will go shallow. And check out the serve. You like it?"

"That 125 mile ace he just hit was pretty good," I replied.

"First serve, not bad. I'd put my right foot in the alley to cut off his deuce court slice and in the ad court stand back two steps. Second serve: questionable. I'd move in big time." On the analysis would go.

Besides assessing techniques and tactics, if Segura was really intrigued by the player, he'd also appraise his competitive character, perhaps even the man's politics and morals.

Along the way, Segura provided insights into how historic greats would have handled the player under scrutiny. Jack Kramer would have been, as Segura liked to put it, "all over" a player's inability to pass crosscourt off the backhand. Bobby Riggs would have exposed his movement and drop-shotted him to death. And Jimmy Connors would have rushed him, in Segura's words, "all day, buddy."

My first encounter with Segura came in July 1982, just three weeks after Connors had won Wimbledon for the second time, defeating John McEnroe in the final. It had been Connors' first major title victory in nearly four years. But Segura had never lost faith.

The night before the final, Segura gave Connors a tactical pointer: If your service return goes low enough to make McEnroe half-volley, McEnroe's best two options are to hit short or high. So move forward and be ready to pounce, either with a volley of your own or immediately with a passing shot. It proved quite helpful, most notably on a point deep in the fourth-set tiebreaker when Connors stood four points away from losing the title.

That kind of simple but powerful tactical insight is relevant for players of all levels. Force a volley short or high. Move forward. That was just one example of the mind of probably the greatest tactician in tennis history.

Segura relished the chance to study, understand, and then, break up an opponent's game. Here are the cornerstone principles of the way he assessed players.

First, study the grips. Certainly the warmup will help, but if possible, Segura recommended watching him play prior. The contemporary Western grip means that low, short balls could be a challenge and that excessive topspin can bounce short. Players with Continental grips usually like to lash the ball crosscourt and are not as effective versus high balls.

Other Segura areas of inquiry: Does the player move better side-to-side or forward? Which spins does he handle better or worse than others? Where does he most frequently aim his serve? Can he serve to all corners of the box? How short is his second serve?

What about the volleys? Does he hit them better off hard or soft balls? And the overhead? No matter who you're about to play, Segura would advise, you should lob them early and often. When you put an opponent on alert that way, you buy a few inches for passing shots.

Segura was always amazed how rarely players studied their opponents in much detail. "You may think the guy's forehand is worse, but it's not that simple," said Segura. "How is it worse? On high balls down the middle, on the run, off short balls?"

A quarter-century after he'd done most of his best work with Connors, Segura told me how the two of them worked together. "There was a special closeness we had in those days," said Segura. "Before matches, he used to say, ‘Coach, do you believe in me?' I said, ‘Jimbo, look, what does that guy do better than you? Does he move better than you? Does he hit the ball harder than you? Does he volley better than you?' Then he'd say, ‘No, coach, we're better.' I got Jimmy in a state of hypnosis. He was spellbound."

Soon the world would come under that spell. But Segura also believed recreational players could create a spell of their own. The ultimate purpose of all that study – before, during, after each match – was to raise your consciousness, to bring your head and heart into the battle.

Apply Pressure

"The name of the game," said Segura, "is to elicit a ball you can attack." So how do you do that?

A big Segura message was that players should take advantage of the openings they'd created with their groundstrokes. If you'd studied the opponent well enough, for example, you knew that once on the run, he was unable off the backhand side to hit anything but a slice. Here was a volley opportunity.

Of course this opportunism made sense for such formidable groundstrokers as Connors, players capable of repeatedly hitting penetrating drives inches inside the baseline that elicit that desired attackable ball. But as I said to Segura on more than one occasion, we recreational mortals are not quite so forceful.

Segura countered: "You can hit a moonball or two or three, can't you? How can the guy hurt you that way?" He was right. Hit a few balls high and deep and you'll soon enough get a shot you can volley. Or given that most recreational players will eventually hit a ball only a few feet past the service line, try another Segura favorite: a drop shot approach.

The service return also created openings. Versus a net rusher on big points, return down the center because the incoming volleyer can't afford to volley too sharply to the corners – and then you'll be able to comfortably pass him on the next shot.

If the serve was short, step around your backhand and pound a forehand – and, ideally, follow it in to the net. Or chip-charge off the backhand. As Segura saw it, even if you got passed, you were constantly sending messages, a non-stop assault.

When it came to serve-volley tennis, Segura had a nuanced view. The body serve took away the angle, but you better be able to strike the serve fast enough so that the receiver couldn't get out of the way and punish the return.

Wide serves were useful so long as you were aware of the proper sequence. Here again, a detailed understanding of strengths and weaknesses was critical. Wide to the backhand could be viable – but was it a one-hander that was usually a down-the-line chip or a two-hander that could be driven in all directions?

And wide to the forehand: Not bad versus those dudes with Western grips who liked to run around backhands. But potentially dangerous against those streaky Continental or Eastern grips that could suddenly slap a winner.

"Why serve-volley every single point?" Segura asked. "Don't ever let them get settled. Mix it up, so then sometimes you get a short return you can attack. Or then, when the guy thinks he wants to hit deep, he'll hit it high over the net."

The engagement Segura demonstrated every time he walked on the court was extraordinary, even near the age of 80. "Come on," he said as he and I went to play a pair of 4.0 players, "let's go kill these guys. They beat me last week and so I want to shut them up today."

There followed an explanation of each player's serve and return tendencies likely as detailed as the one Segura had given Connors prior to a big match. One guy could only lob off his backhand. The other's serve just about always went wide in the deuce court. But if the competitive intensity of a man in his ninth decade was scary, it was also something that could be learned and mastered far more easily than shots such as Segura's remarkable two-handed forehand or his deft volleys.

Play the Score

In the same way that a quarterback grasps the significance of downs and yardage, or a baseball pitcher is aware of the count, Segura placed deep importance on being aware of what the score was.

On the macro level, this made sense. Segura, after all, had been a sickly childhood from a poor background who'd worked his way right to the top. At every rung, he'd known the score: the people, the places and what was required for him to succeed.

Segura was fanatical about keeping the score in mind as you made tactical decisions. If you were up 40-love, why not try for an ace, a drop shot return, a big down-the-line groundstroke?

But points like 15-30 were when it was time to batten down the hatches – too tight a time for an adventure. If those two scores were more obvious situations, others were nuanced.

At 30-all, if the receiver had an Eastern or Continental grip, be leery of a serve-volley to his forehand, as he could suddenly crack one past you down-the-line or crosscourt. 15-all if you were up a break was different than 15-all if you were down a break. 40-30 was the time you absolutely must get your first serve in and close out the game. If you were serving for a set, winning the first point was vital.

All of this was a way to continue the relentless application of pressure. Watching a student of his take the lead versus an opponent, Segura said, "Squeeze this guy. Stay on him, stay on him. Don't let him get up off the ground." The score was the omnipresent reminder and barometer of which punches should be made when.

These three concepts – assessment, the application of pressure, playing to the score – were what Segura believed separated the smart player from the stupid one. The stupid player merely trotted out his tools and hoped for the best. The smart player studied both himself and his opponent.

And even more, a truly ambitious player would come away from a match and see what skills he needed to sharpen. Playing a great lobber like Bobby Riggs, for example, helped Segura improve his overhead. Serving to a chip-charge master such as Kramer aided Segura's own serve and helped him see that against these kind of returners it was often helpful to serve more to the forehand than the more staccato-like chip backhand return.

Perhaps most of all, Segura recognized that tennis was an interaction, a relationship between two sets of skills and two psyches. As he often said, "Just me and you, baby, in the arena. Just me and you."

A Drill for the Ages

Segura was among many coaches who have told me that not every drill is a precise replication of a point. Many drills are intended to activate a player--to get the player to move around the court with high-octane intensity and strike the ball in a dynamic manner. Over the course of 30 unforgettable minutes, Segura had me run a drill that he said, "Jimmy loved. We used to do this for hours and hours."

The steps were simple, but the technique required to execute the drill, and the valued gained from practicing were exceptional.

This is the progression:

Server in deuce court serves wide.

Returner strikes return deep, crosscourt, ideally, with significant pace.

The Returner then moves forward into the net area. The goal is to see the wide serve an attackable short ball.

Server--presumably a right-hander--then replies with a forehand down the line.

The Returner then strikes a sharp crosscourt volley – ideally for a winner.

If the Server can reach the volley he replies with offensive lob. As an aside Segura would explain his own offensive lob was "the best in the business, buddy."

The Returner then tries to bury the overhead for a winner.

Do this drill 10-15 times on one side of the court. Then switch to the other. You will see how much energy and skill you have – the dynamic qualities of your strokes, the strength in your feet and legs, your ability to dash forward, strike a volley forcefully and, if necessary, summon up the strength to hit an overhead.

The drill explains much about how Segura and Connors spread the dimensions of the court – and the techniques required to conquer it with the commando-like fury each brought to the game. Obviously you won't play every point this way. But to practice this way helps you develop confidence in a wide range of skills that lead to winning tennis.