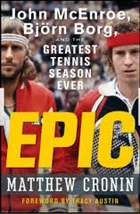

A Little Boy or a Midget:

John McEnroe

Matt Cronin

|

John with his parents, John Sr. and Kay in Douglaston. |

Like many athletes who weren't blessed with a large frame and Olympian genes, John McEnroe describes his rise to the top of the tennis world as improbable. But it really wasn't. From the time he first picked up a racket, he had a few intangibles that would work in his favor - an unquenchable thirst to win, a frenetic competitiveness, and amazing hand-eye coordination.

John Patrick McEnroe Jr. was born on February 16,1959, at the American military base in Wiesbaden, Germany, where his father, John Patrick McEnroe Sr., often known as J.P. McEnroe, was stationed with the air force and his mother, Kay, worked as a surgical nurse.

After J.P's discharge in 1960, the family moved to Flushing, New York, and later settled in Douglaston, a middle-class section of Queens. There were two younger McEnroe brothers, Mark (born 1962) and Patrick (born 1966), the latter of whom became a fine tennis player himself. J.P. earned his law degree in night school, and was talkative, demanding, and full of life, with a loud joke or opinion always on hand.

Kay, a no-nonsense mother who describes herself as someone who likes "everything done yesterday," had a harder view of life and never trusted outsiders. "Unfortunately, I'm like her in that way," said her oldest son.

|

John with junior rival Larry Gottfried. |

McEnroe described his Douglaston neighborhood as something out of Leave It to Beaver, where he and his friends would spend long summer nights playing stickball out on Rushmore Street - a fine way to improve the eye-hand coordination so necessary for tennis. But much as he loved to play sports, McEnroe wasn't physically blessed, and in his youth he was short and pudgy and had a target on his chest for the neighborhood bullies.

He was called a runt by older kids but continued to engage in every sport available to him. He never minded getting his nose bloodied or causing a few scrapes and bruises himself. Early on, he developed a Napoleon complex.

Kay quickly instilled a no-quit attitude in him. Once, after he fell off his bike and hurt his arm, she told him to grit his teeth and go play tennis. Three weeks later they discovered that McEnroe had actually broken his arm. "We were rookies at the parent job," his father said, "but we got better at it."

Nothing would stop the McEnroes from climbing up the social ladder, and they moved three different times while in Douglaston. "They fully bought into the American dream," John Jr. said. "But it was a restless dream, and a big part of it was where you lived."

His father likes to tell the tale of how one day in Central Park he was pitching balls to his little son, who proceeded to crack one hard line drive after another. A woman walked up to McEnroe Sr. and asked, "Excuse me, is that a little boy or a midget in disguise?" The story smacks of urban legend, but somebody somewhere saw that Johnny Mac had a unique understanding of games played with balls. Eventually they would become his puppets.

|

Mac took every error out on his own psyche. |

Blessed with an amazing touch, McEnroe picked up tennis quickly and once said that he could actually feel the balls through the racket strings-no small feat for even the most superior of athletes. He was competitive in everything, saying that he had a "rage not just to compete, but to compete and win."

He never got used to losing and absolutely hated defeat. As a kid, he would scream at himself when he missed a negotiable shot and cry when he lost. No linesmen were around to yell at back then, so he took every error out on his own psyche. Strangely, McEnroe also began to resent the spectators who came out to watch him play, saying that he couldn't stand that they were having a jolly old time eating, drinking, and discussing life in the stands while he was on court laying it on the line.

McEnroe was a smart kid who did well in elementary and middle school and enjoyed chess. His mother recalled a time when he came home from the seventh grade and said, "John Dupont got a 98 in the lab and I only got a 96. I told him to sit down and study and he won the academic medal. He was a competitor."

|

A competitor—in everything. |

J.P. was an ambitious father who loved his son's sport so much that he not only attended just about everyone of John's matches, but would also watch him practice hour after hour. This can be an incredibly boring experience given the monotony of tennis drilling routines, where a player can be asked to hit fifty balls down the line with the same stroke.

John Jr. would say that at times he tried to push his dad away, thinking that instead of watching him drill he should be taking his wife to lunch. But J.P. McEnroe never went away.

Even in 2006, when McEnroe returned to the ATP Tour to play doubles at a tournament in San Jose, J.P. was there soaking it all in at courtside. He thoroughly enjoyed himself as John won his seventy-eighth title with Swede Jonas Bjorkman over a group of underwhelming twenty somethings.

Even though Douglaston had decent public schools, like many Irish Catholics at the time, the McEnroes decided to send their kids to a Catholic school, St. Anastasia's. But when John was in first grade, a nun told Kay that he was too smart for his class and to send him elsewhere.

So off little Johnny went to Buckley Country Day School, a twenty-five-minute ride away in the exclusive Roslyn town. He excelled there, always wanting to score the highest grades, a commitment that was obvious to his teachers.

|

After 3 weeks of lessons, Douglaston club pro Dan Dwyer predicted Mac would play at Forrest Hills. |

After a move to the more prestigious Douglaston Manor, the McEnroes joined a small nearby tennis and swimming club, the Douglaston Club, in 1967. J.P. liked tennis and put rackets in his boys' hands. It was a way of climbing the middle-class ladder, because tennis was still an exclusive sport and still a year away from breaking out of its amateur status.

Johnny Mac began to take lessons and his talent was unmistakable. Two weeks after his first lesson at the age of eight, he entered the club twelve-and-under tournament and reached the semifinals. Three weeks later he beat all three of the other twelve-year-olds who attained the semis. The club pro, Dan Dwyer, said at a banquet, "I'm predicting we are going to see John at Forest Hills someday."

McEnroe says that as a kid he was fast, could see the ball like a grapefruit, and could anticipate where his opponent's balls were going. That ability made him the player he would later become, as he always seemed to be in the right spot at the right time. That ability is also a crucial part of a net rusher's success, since a large part of being a successful volleyer is understanding where your opponent is going to aim his passing shots.

Due to his small stature, McEnroe was not a serve-and-volleyer at a young age. He was a scrapper who dug out balls time and time again and began to adeptly mix up speeds and spins. Mac watched the game and learned all its potential shots.

He tried different lengths of backswings, slid his hands up and down the racket to test its weight, stood in varied positions, tried topspin, backspin, and sidespins. He hit high, he hit low, he hit between heights and aimed down the middle. Like Borg, he pounded balls against the backboard when he couldn't get a match. The racket became an extension of his arm.