Barry MacKay:

The Great Ohio Bear

Matt Cronin

When former U.S. No. 1, tennis broadcaster and tournament director Barry Mackay passed away in mid May, it wasn’t followed by the silence you hear when a pro player tosses a ball up to serve. People from all walks of tennis life came forward to pay tribute to the great Ohio Bear.

Barry MacKay was the last of the good hearted, independent tournament owners and promoters. He was revered by tennis insiders who knew him as a genuine human being who didn’t play games or, despite his status, try to big time anyone. He was known by many as a genuine friend—and many of those friends in tennis started out as complete strangers.

MacKay was unique: a tournament director with a personality that people loved. He was not some glad hander who would only extend his arm to people who might do something for him. He was a legitimately nice guy who gave all of himself to the elite athlete or the common man. He treated people how he would like to be treated himself.

"He was especially kind and considerate and helpful to me before my career even got started, dating back to my time as a tennis player and fan in high school," recalled longtime tennis agent Tom Ross who knew MacKay for 40 years.

"He seemed to be able to relate and empathize with everyone he came across, and his "can do" nature and personal touch with players, sponsors, media, administrators and fans created a fountain of goodwill."

He was the personification of humane. But he was also one of the last men to independently run a high level pro tournament and do so without the backing of a large corporation.

MacKay was not without his faults. He enjoyed eating and drinking as much as he did knocking off crisp volleys and belting out his signature call on TV: "And there it is!"

When he passed away, everyone who knew him recalled "The Bear's" infectious smile. And most had a story about how he had helped them when he had no financial motivation to do so.

"I met Barry in about 1983 when I was first working on the Winning Edge video with John McEnroe and Ivan Lendl," recalled John Yandell, the founder of Tennisplayer.net.

"I cold called the guy. There was no internet in those days and I had no idea where to get an indoor court surface like he used at his tournament for our filming."

"He didn’t have to even talk to me. Not only did he help me with the court, he took a real interest in the project and was one of the first people I showed the rough cuts to."

"From that time on he treated me like a friend and for someone just getting started, that was huge and a source of pride to me."

"Barry was one of the first people to realize the coaching potential of the filming we were doing of the top players. He gave us complete access to his event and much of our early footage was filmed there," Yandell added.

"I still remember looking at our high speed video with him in the media room at his tournament in San Jose. It's too bad there aren't more people in the modern game with the same vision and values he had."

MacKay grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, an unlikely tennis mecca, which also produced such champions as Bill Talbert and Tony Trabert. (Click Here for the Secret History of Tennis in Cincinnati!)

A tall net rusher with a huge serve, he was an Ohio state high school champion and then led the University of Michigan to the NCAA title in 1957. He then made an immediate impact at the highest levels of amateur tennis, helping the US to a 3-2 victory over Australia in the Davis Cup final.

At Wimbledon in 1958, he upset Aussie great Neale Fraser, reaching the semis before losing to the legendary Rod Laver. In 1960, he became the United States top ranked player, when he won five tournaments.

Although known as a serve and volleyer, his game was complete enough to win the Italian Championships on red clay and the U.S. Clay courts. He also made five U.S. Davis Cup appearances.

MacKay liked to tell the story of his last Davis Cup appearance and what happened before the final against Australia, when he was in line to turn professional and join Jack Kramer’s barnstorming tour.

Kramer invited MacKay and Butch Bucholtz (who would later become the tournament director of Miami) to join the tour. But MacKay, already a wheeler-dealer in the making, decided to try to negotiate the price upward.

"We knew Jack was offering $50,000 for two years apiece, but at the time, Butch and I were the top two players in the United States and we thought we deserved more," MacKay once told me.

"Butch was intimidated by Jack, so he wanted me to do the negotiating."

"We sat down and Jack offered us the $50,000, and I said, ‘We think we’re worth $60,000.’"

Jack said, "No problem boys, but here's the deal. I’ll give you $60,000 if you go down to Australia and win the Davis Cup. But if you lose, you only get 40,000!"

"Butch and I settled for $50,000 and got out of there real fast."

In 1966, MacKay relocated to the San Francisco Bay Area and in 1970, became the tournament director of what is now known as the SAP Open. The tournament is now played in San Jose, but began at the Berkeley Tennis Club, then later moved to the Cow Palace, then downtown San Francisco.

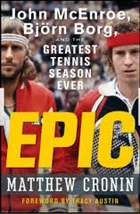

While the tournament director, MacKay demonstrated a magical ability to recruit many of the greatest players in tennis history for what was really a relatively small event on the world tour. Jimmy Connors, John McEnroe, Bjorn Borg, Pete Sampras and Andre Agassi all played year after year, and (in addition to some substantial appearance fees) Barry MacKay was a central reason.

"Barry MacKay is a great guy," John McEnroe was quoted as saying in 1983, a year when that was one of his very few positive utterances regarding the tennis establishment.

MacKay always made sure Mac had the best suite at the Mark Hopkins hotel, a few bottles of champagne, and a new Volvo to drive around on the San Francisco hills where he enjoyed going through a clutch and a set of brakes during his week in the city.

But in 1995 MacKay sold his share of the tournament to the owners of the NHL San Jose Sharks and the tournament moved south to the location where it is today. He remained tournament director for a number of years, but under circumstances he never discussed publicly, was replaced by the corporate owners.

I'll never forget the look on his face when the Sharks group all but forced him into an on court retirement ceremony during his last year. "I'm not going anywhere else Matt, but I guess they want me out of here," he said to me that night.

When MacKay left, the tournament lost its homey feel in an arena some called the "Shark Tank" and many in the media described as a cold white dungeon. The Sharks group eventually--not unpredictably--lost its interest in tennis. 2013 will be its last year.

That would have never been the case with MacKay, who would have sold the shirt off his back to keep the tournament alive and kicking in Northern California.

"That tournament was never the same after he stopped running it," said former player and now coach and broadcaster Brad Gilbert, a Bay Area native. "They are a corporation and he is an individual. That was his baby."

But perhaps it was inevitable that MacKay would have lost control of the tournament eventually, as it's rare these days to find tournaments that are run by one person--even so-called small tournaments like San Jose that cost well over $1 million to put on.

The women’s tournament at Stanford is owned by the giant sports agency IMG. San Diego is owned by another big agency, Octagon. IMG also owns Miami, and Octagon runs Cincinnati for the owner, the deep pocketed USTA. Meanwhile, billionaire Larry Ellison bought Indian Wells.

The clay court tournament in Houston still exists only because the super wealthy members of the River Oaks country club make annual contributions to keep it alive. The L.A. men's tournament is struggling and could be sold as it is now owned by the USTA’s Southern California section, which is tired of taking losses.

For years after MacKay was forced out of his tournament, he continued his TV commentary work for a host of networks. Even during boring matches, he would keep his interest level up, and despite having seen thousands of points played, he always seemed to be happy describing them.

"Barry was a man blessed with Midwestern warmth, avuncular charm and the best pipes a broadcaster could ever hope for," said one of his former partners, Leif Shiras.

"His voice was a deep dulcet tone that made listening easy. You could also hear in his commentary that he just loved the game of tennis. A match would be getting good, drama building and it wasn't just the crowd who was on the edge of their seat, so was Bear."

"It's on the line" or "net cord" breathlessly punctuated dramatic moments. Barry's post-match wrap was old school all the way -- "There it is! It was simple and straight forward and elegant. Like Barry himself."

Few people in tennis realized that Barry had been ill for a period of many months before his passing. Some friends expressed remorse that they never had the chance to really say good bye.

But that was probably the way Barry wanted it - for people to remember him at his best, running his tournament, making a dry comment on television, or coming up with a big smile to say hello.