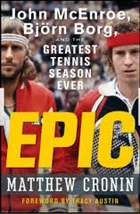

Taming a Passionate Spirit:

Bjorn Borg

Matt Cronin

|

Bjorn Borg's hometown: Sodertalje, Sweden. |

Bjorn Borg's father, Rune, loved table tennis, but it didn't put bread on the table in his town of Sodertalje, Sweden, so he kept his day job selling clothes while his wife, Margarethe, stayed at home. But Rune still competed like mad, and in 1965 he won first prize at the city table tennis championships: a tennis racket.

He gave it to his only child, nine-year-old Bjorn, who immediately headed off to discover what it would feel like to hit larger balls into a larger court and at the same time actually run after them, unlike in the more stationary table tennis.

Bjorn's first wife, Mariana Simionescu described his hometown, Sodertalje,as "a row of little cubes." She says there is a sameness there, a consistency, that informs the character of the man she married.

There was a small tennis club in Sodertalje, but as a beginner Bjorn had a hard time getting matches. So he did what every kid of his era did: he found something to hit against that would hit back. That turned out to be the family's garage door, and it would be a perfect opponent. When boy hits ball against door, ball always comes back-unless boy misses and sends ball over it or off to the side.

|

King Gustav built the first Swedish court in 1881 and played 3 set matches at the age of 84. |

"I was obviously crazy about tennis from the beginning," he said.

So were many of his countrymen. In 1881, the crown prince who was to become King Gustaf V built Sweden's first proper court at Tullgarn, his private country castle. The first covered court was built in Stockholm in 1896.

During the nineteenth century, eight tennis clubs were founded, and by the mid-1950s that number had reached four hundred. When Borg began to play, approximately eight hundred clubs existed with some sixty thousand players.

King Gustaf, who occupies a critical place not just in Swedish tennis lore but in European tennis as well, was said to have played two three-set matches in one day at the age of eighty-four.

Borg likely knew little of Curt Ostberg, the first significant male player from his country, who beat French Hall of Famer Jean Borotra to win the British indoors in 1934, but Ostberg's status as a top-flight player confirmed that Sweden was there to be reckoned with as a tennis power.

|

Curt Ostberg beat French Musketeer Jean Borotra in 1934, putting Swedish tennis on the world map. |

Once Borg grew older, he was surely made aware of Sven Davidson and Ulf Schmidt, who became the first Swedish pair to win a major when they won the 1958 Wimbledon doubles. After banging and thumping balls at the thick garage door for up to four hours a day, Borg learned all the tricks of tennis wall ball: which height, spin, and amount of velocity to use to get the desired return.

Slugging against backboards bores some people, but not players like Borg, who enjoyed the monotony of its consistency. You couldn't hit through the wall, you couldn't coax an error out of it, but what you could do was imitate it: hit the ball back again and again until the human became as steady as the wall.

Borg would set up tests for himself imagining that he was playing for Sweden against the United States or Australia, the two preeminent Davis Cup nations. "I used to say if I miss one the Aussies or U.S. will win the Cup," he said. "Or if I don't miss for ten shots, Sweden wins."

Borg won his first junior tournament at age eleven at the Sorrnand County Championships. One day a top Swedish coach, Percy Rosberg, saw Borg play when he was scouting a couple of older kids and invited Bjorn to train with him at the Salk Club in Stockholm, even though he didn't like Borg's table-tennis-style flick of a forehand. For the next five years, Bjorn made the ninety-minute train trip from Sodertalje to Stockholm every day after school.

|

For 5 years, Borg made a 90 minute train trip everyday to train at the Salk Club in Stockholm. |

At first, the club's better players regularly destroyed him. Two years later, he took them all down. "His footwork was fantastic," Rosberg says. "Even then he would hit one more ball back against the opponent."

Borg's parents never pushed him, and he lived a fairly normal boyhood, also playing soccer and ice hockey. In the summer he and his parents would take a small boat out and sometimes sail past Stockholm to the island of Moja. On the journeys he would gaze at the water, perhaps designing combinations that would make it impossible for fellow players to send him off the court.

He likely dreamed of being a king, not of his nation's political courts like Gustaf, but of the world's tennis courts, where majestic ability mattered more than royal blood.

He didn't take tennis lessons for his first three years, which is one of the reasons why he started to play with two hands on both sides-that and the fact that his racket was too heavy for him and he simply wasn't strong enough to produce enough pace.

He didn't develop classic strokes, but he honed his own, which were consistent and full of topspin. As he grew stronger, he began to hit a one-handed forehand but kept his left hand on the racket while whipping backhands.

|

Borg ignored the experts who said he'd never get anywhere with his two-hander. |

"Some people at the club said I'd never amount to anything with my two-handed shot," Borg said. "Maybe the reason why I got so far was because I wouldn't listen."

Later he would say his success was made possible because of his "crazy" western forehand grip and "wristy" two-handed backhand, both of which forced him to hit with exaggerated overspin. "Violent topspin is my trademark, and if I hadn't had the courage to improvise.

when I was young, and shatter the conventional beliefs about grips and depth, I might still be struggling through the qualifying rounds at Wimbledon rather than shooting for a string of successive titles."

When the cold Swedish springs turned to summer, Borg would get up at dawn and head to the courts. His mother wouldn't pick him up until ten at night, when the sun was still high in the Scandinavian sky. He played as much as he could, and when he wasn't hitting he watched others compete.

"Even at night I felt like getting up to play," said Borg, who added that the winters weighed on him heavily because he could only play two hours a day indoors and because school sucked up a lot of his time.

"He'd spend eight hours a day on these courts," said LeifJohansson, a future Davis Cup teammate who was three years older than Borg and who trained at the same club. "He was out here always."

|

Becoming the Iceman took Borg many years. |

Another Swedish player, Tenny Svensson, pointed to Borg's independent streak and singular focus. "He wants to do things his way. That's probably why he became the best: he made up his mind he's going to do it, and he went for it."

It was then that the stories of the petulant young Bjorn popped up. He would later be called "Ice Borg," but as a young teenager while playing at the clubs, he admittedly had a terrible reputation as a racket thrower and a player who would loudly curse his own mistakes, his foes' good shots, and questionable line calls.

In early Borg lore, after Rune saw his son throw his racket, he wouldn't allow him to play for six months, which is why Bjorn eventually developed an icy exterior. Whatever the truth of that story, there is no doubt that young Borg fought to control his temper. "I wanted to win so badly that it drove me mad when I lost," he said. "One day they suspended me for two months and I was forbidden to go to the club. They said anyone who behaves like you has no business to be on a tennis court." Borg said he learned a lot in those two months and realized that he would perform better if he stayed calm. Lesson learned.