Tomas Berdych's

Forehand

By John Yandell

Could there be a bigger contrast in technique than the forehands of Rafael Nadal and Tomas Berdych, as demonstrated in the 2010 Wimbledon final? Look at the key components in the stroke: grip, stance, hitting arm configuration, torso rotation, finish, shot trajectory, and spin. Berdych and Nadal probably define the polar extremes in the modern game. (Click Here for a full analysis of Rafa's forehand.)

Over the years, we have studied all these elements closely in articles on Tennisplayer. We've looked at the prevalence of the open stance variations and the more extreme semi-western grips. We've seen how these factors have also naturally facilitated radically increased torso rotation in the forward swing. (Click Here.)

We also analyzed the increasing prevalence of exotic finishes. We've seen how the windshield wiper has become ubiquitous, even for players with more conservative grips like Roger Federer. We've also seen how the reverse finish, a concept developed by Robert Lansdorp, has also become more and more prevalent, used regularly by Nadal, and situationally by virtually all top players.

We've also seen how many of the top players including Federer, Nadal, and Fernando Verdasco have evolved the straight hitting arm configuration, making contact further in front with the elbow straight, and how this is interrelated to stance and extreme torso rotation. (Click Here.)

And then there is Tomas Berdych. Yes, you can see Tomas do many of the same things with his forehand - hit open stance, rotate the shoulders further in the swing, wiper or reverse his finishes. But these elements are less frequent variations compared to other players. As with Juan Martin Del Potro, many components of Berdych's forehand are more conservative--components some critics have branded old school and no longer relevant at the highest levels of the game. (Click Here for more on Del Potro's forehand.)

Which raises a critical question: does technique make the player or does the player make the technique? Is Roger Federer great because of his unrivaled variety of wiper finishes? Or is mainly that he is Roger Federer and that makes him really good at using the wiper? Would Berdych be better with Federer's technique or do different components work as well or better in the context of his own game style?

And then of course, there is the question for the vast majority of the planet's tennis players. Hoe does what elite players do apply to me? If Rafael Nadal uses a reverse finish on half of his forehands, is that something I need to do to win the club singles championship?

Let's go through the components on Berdych's forehand and see what light we may be able to shed on these and other questions.

Grip

Compared to Nadal who is as far under the handle as any pro player, Berdych has a much less extreme grip, what we have referred to in the past as a mild semi-western. It's similar to the grip of Andre Agassi or James Blake, two other flat hitters who also take the ball early like Tomas.

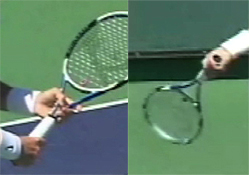

|

A mild semi-western grip with the index knuckle on bevel 4 And the heel pad on bevel 3 or slightly lower.

|

It's always hard to tell with absolute precision from video - and one day I am going to go out on the court with all these guys and take close ups photos during matches. (Right.)

But based on the imagery we have, it appears that Tomas has his index knuckle in the center of the fourth bevel. It also appears that most of his palm is behind the racket handle, with his heel pad on bevel 3 or maybe shifted halfway downward toward bevel 4. (For an explanation of how to understand the bevels and modern forehand grips, Click Here.)

So Berdych's grip is shifted slightly toward the west compared to Del Potro, but the result in both cases is the ability to hit relatively flat forehand bombs. (By the way, we hope eventually to develop spin information on these two players to go with our data base on Federer, Nadal, and others.)

At 6'4" or 6'5", their extra height raises the natural strike zone a few inches. What that means is that they can still make contact between his waist and mid-chest on a ball that would be more difficult for a shorter player using similar grips.

Preparation

The more we look at top players, especially on the forehand, the more we see the incredible diversity in the way they combine technical components. But probably the closest thing to a universal element across the grip styles is the turn.

Like all top players, Berdych starts the preparation by turning his feet and body sideways. As we have seen, there are many variations in the footwork to get this started, depending on court position and the oncoming ball. (Click Here.) But what the players have in common is the amount of shoulder turn and the stretch of the left arm.

As the body starts to turn, players keep both hands on the racket, which makes the first part of the racket preparation is automatic. The racket goes back as the body turns. At a certain point, however, the hands separate. This is the true start of the backswing as racket hand starts to move independently upward and backward.

As the backswing starts, the opposite arm straightens out and points across the body at a 90 degree angle with the side fence. The torso meanwhile continues to turn, and the final result is that the shoulders turn until they reach a right angle to the net, and usually in the pro game, turn slightly further.

Berdych separates his hands relatively early compared to some players, but he still ends up in the same full turn position. His opposite arm is level or parallel with the court surface and perpendicular to the sideline with the shoulders fully sideways.

A key part of the preparation is the set up on the outside leg. When players are near the center of the court, this coincides with the completion of the turn. The weight is on the outside back leg, with the knees bent. Notice that the left side and the left leg are rotated sideways as well as the rest of the torso. The actual position of this left leg can vary, as we shall see, depending on the stance, but it is critical that it turn.

When Tomas is hitting with a neutral stance, he sometimes takes the forward step at the completion of the turn. Other times he has simply started or is in the middle of the step.

When he is hitting open stance, however, the left leg will still be offset to the side. But the loading on the outside or right leg is a constant regardless of the stance or where he is in the step.

Backswing

Top players reach the turn position, typically, when the racket is at the top of the backswing or slightly on the way down. Berdych has a high backswing motion, with the racket hand reaching the top of his head, or sometimes even above. Like many players he turns the racket on edge after the hands separate, with the tip angled forward toward the opponent.

As the racket starts downward Tomas straightens out his arm and closes the face to the court, sometimes so that it is completely parallel to the court surface. This happens typically when the arm is pointing directly backward at the back fence.

Again it is fascinating to see the differences among the top players. Federer has a lower backswing than Berdych, but as with Tomas, he turns the racket on edge, angles the racket tip toward the opponent, and then closes the face as the racket comes down.

Del Potro has a much higher backswing, but angles the tip upward and backward, pointing almost at the sky, making his motion appear even larger than the actual path of the hand. But unlike Federer or Berdych, he does not close the face as the backswing descends, keeping it almost completely on edge.

Nadal has a lower hand position like Federer at the top of the backswing, but points the racket tip upward more like Del Potro. We've seen that even the above descriptions don't exhaust the possibilities and that virtually all top players have their own unique combinations.

So tell me, is it possible to say one or the other backswing is technically superior, or that any of these elements correlate with grip style or even with each other? (Click Here for more on backswing variations and complexities.)

Hitting Arm Position

However, there is one key commonality on the backswing. This is that all the various motions deliver the arm and racket to the hitting arm position at the start of the forward swing.

This is one place where the human eye and even experienced coaches can be deceived. Players may (or may not) have the face completely closed midway down in the backswing. But by the time the racket reaches the bottom they have set up a distinctive hitting arm position for the forward swing.

This transition happens in about a tenth of a second, sometimes less, which is why it is so difficult to see with the naked eye. Yes, the racket face may still be partially closed, but this is a function of grip, not what happens in the backswing. (Click Here for more on this.)

Hitting Arm

We have seen in past articles that both Federer and Nadal, at least on most balls, use what we have termed the straight arm or straight elbow hitting position, as does another guy with a huge forehand, Fernando Verdasco. This is in contrast to what has been called the double bend, in which the elbow is tucked in toward the torso.

On the world tennis messages boards, coaches and players have debated this, with some concluding that the straight arm is the superior configuration, the wave of the future, the only way to teach, etc, etc, and meanwhile, that the double bend configuration should be discarded with wooden rackets. They point to the top two players in the world and ask: who can argue with Federer and Nadal?

Then along come two other players: Robin Solderling and Tomas Berdych, who are now crushing forehands with as much if not more pace than anyone in the game. But both of these players use the double bend hitting arm structure, the same configuration used by players such as Andre Agassi and Pete Sampras. (Click Here for more on the double bend.)

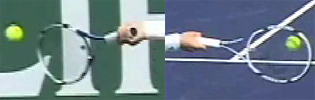

You can see how Tomas sets up the double bend clearly in the video. Watch how the face closes as the racket moves downward in the backswing motion, but then watch how his hitting rotates and then falls into the double bend a split second before the forward swing. Note that the elbow is tucked in and the wrist is laid back 60 degrees or more.

So I don't think we can quite call the double bend obsolete yet. Again, this is the issue of talent versus technique. If a great player uses a certain technical element does that de facto make that element superior?

Until we clone Rafael Nadal and teach him a series of different forehands, that question is always going to be difficult to answer. What we can say for sure is that both configurations have been proven effective at the highest levels of the game.

Then there is the question of what applies at all other levels. The issue here is that hitting the straight arm forehand is associated with predominantly open stance hitting and also with extreme forward torso rotation. Those are more difficult elements in my opinion for most players to master, especially for a player who is developing the shot for the first time or attempting to restructure it technically.

Junior players or college players, it could be a different story. That may be worth the experiment in many cases. (For more on that and how USTA Player Development is working to develop more Spanish influence, Click Here.)

But the double bend will definitely also work with advanced elements like open stances and more torso rotation. It also pairs naturally with a simpler, more classical swing patterns. And we can see an example of how that works at the highest levels with Berdych.

Stance

If you look at the Berdych forehand clips in the Stroke Archive you will see that Tomas hits more neutral stance forehands than any other top player. In the center of the court, there are 34 examples, and half are neutral stance. This is on a relatively high bouncing hard court. If you watched his matches at Wimbledon, you saw that the percentage of neutral stances there was at least as high, if not higher.

As noted above, player height appears to be increasing in the pro game. If you are 6'5" you can step in naturally on a higher ball that would force a shorter player to either take the ball significantly earlier, or move to an open stance to deal with the bounce.

Some analysts say that the neutral stance generates more "linear" momentum forward into the shot, while the open stance generate more "angular" momentum through the rotation of the torso. That may be true, but this is a question that could only truly be answered by 3 dimensional measurements of what happen to the racket head at contact.

I like the neutral stance for a completely different reason, at least when you are learning or correcting a stroke. This is because it promotes the full body turn. My experience with the overwhelming majority of club players is that they never fully turn or stretch the left arm, and that this problem is usually worse when they have been taught or try to hit primarily open stance.

The fact is that the step forward with the left foot into the forehand naturally brings the left side around. When you step in you can't help but turn your body. The step across and forward into the neutral stance automatically turns the left hip and left shoulder. This in turn puts the left arm in position to stretch naturally all the way across the body.

In my experience, the left side and the left foot gets stuck during the turn for too many club players. They never get the arm fully across or the shoulders turned 90 degrees plus to the net. Learning to hit neutral stance is often a miracle cure for that problem.

Torso Rotation

The third element that is so often paired with open stance and straight arm hitting is massive forward torso rotation. Pro players are setting up in open stances, launching into the air in the forward swing, and then landing with the rear shoulder actually facing the opponent, or something close to that.

This factor may have developed partially as a response to the height of the contact in pro tennis, but it is facilitated the incredible, increased athleticism of the players. As players were forced to play more up in the air they found they could rotate their bodies much more than with one or both feet stuck on the court.

Using more rotation, they could unload on the ball moving in any direction, because their bodies were in the air. But is it something that most players should or need to imitate? (For more on the critical factor of contact height, Click Here.)

But we can see another option with Berdych. Yes, he is more than capable of elevating and hitting open stance and using extreme body rotation. But when he sets up in the neutral stance, this rotation is restricted.

Instead of the back shoulder rotating 180 degrees and facing the opponent, the rotation is closer to 90 degrees. The shoulders go from about perpendicular to the net at the completion of the turn, to about parallel to the net when Berdych reaches the extension on his forward swing.

The interesting thing is that, for Berdych at least, this compact, relatively minimal motion is sufficient to generate screaming laser forehands. Assuming the ball height is within the player's strike zone, I believe that can work the same way at the club level. What this means is that some players may be able to develop a better forehand by simplifying and eliminating the kind technical complexity that is often just counterproductive overkill.

Extension and Finish

Robert Lansdorp recently told me that the only players on the tour that still followthrough over the shoulder are the ones who are old and bald. As he observed the evolution of the game, he began to teach the wiper followthrough, or what he called the downward finish, because he saw so many of the players were using it to create additional topspin, spin necessary to deal with the increasing velocity in the pro game. (Click Here.)

And that is the overwhelming trend--with Tomas Berdych as one of the very few exceptions. Again, he certainly uses the wiper as well as the reverse finish, but if you study the body of his forehands in the Stroke Archive, you will conclude that most of the time his followthroughs are over the shoulder.

Berdych reaches the same classic extension point on his drives as most top players. This is with the wrist at eye level and at about the left edge of the torso, and with substantial spacing between the racket hand and the torso.

This extension position is what in my opinion creates maximum velocity. But from there, rather than finishing around the shoulder or the torso, Berdych continues moving the racket backward in the classic over the shoulder wrap. This happens naturally as a function of the relaxation of the arm in the deceleration phase. This is the final element in the allegedly "old style" forehand.

So the entire stroke sequence goes like this: a relatively moderate grip, a great body turn, a double bend hitting arm structure, a neutral stance, great extension through the swing, and a natural over the shoulder wrap.

Is that the right forehand for you? As I've said before, there really isn't a simple answer to that question. Maybe you just enjoy experimentation with the complex elements in modern technique. That's cool. Maybe you also put them together in a way that produces great competitive success. Or not.

Or maybe you find that simpler can be better and that you a player like Berdych can inspire you to create a forehand that has fewer complexities--but can be a weapon at any level. These are questions players should only answer for themselves.

That's what is so great and also fascinating about tennis - the amazing range of creative choices and decisions you get to make about all the various strokes. And if you're like me, you enjoy studying a player like Tomas Berdych because he provides model elements for one of the alternatives in the wide range of possible options.